Part IV. Case Studies

A Neighborhood in Transition: Hough, Cleveland

Peter Leahy and David Snow

Of the various territorial units within urban areas, none have commanded more attention among students of the urban scene than the residential neighborhood. Yet neighborhood transition and the factors underlying the process are still not entirely understood. This is especially so where racially changing neighborhoods are concerned. It is known that racial transition and neighborhood instability are not necessarily linked. But it is less certain why some neighborhoods undergo racial transition more rapidly than others and why the transition is sometimes accompanied by sudden physical deterioration. As a recent analysis of residential turnover in several urban neighborhoods concluded, “We still have much to learn about . . . how neighborhood transition occurs” and what accounts for variation in this process from one neighborhood to another.[1]

This paper seeks to further understanding of neighborhood transition in general and of racially changing neighborhoods in particular by analyzing the transformation of Cleveland’s Hough district from a white, middle-class neighborhood into a black slum-ghetto.[2]

Methodology and Data

The case-study approach has been used here to investigate neighborhood change in Hough. While this methodology does not permit generalization beyond the neighborhood (since events in one neighborhood may be different from events in another), it does provide an opportunity to study a transition in much deeper detail. To strengthen the validity of our findings we also followed a methodological lead suggested by another neighborhood researcher. Noting that it is precarious to infer the cause of residential transition from census data alone, it has been suggested that an understanding of the process might be improved if the researcher were to acquire greater familiarity with the neighborhood(s) in question by participant observation or some other qualitative technique.[3] That directive seemed appropriate since most analyses of residential transition and neighborhood change have been based primarily, and often solely, on census tract data. Both qualitative and census data were therefore used in our analysis of Hough’s transition.

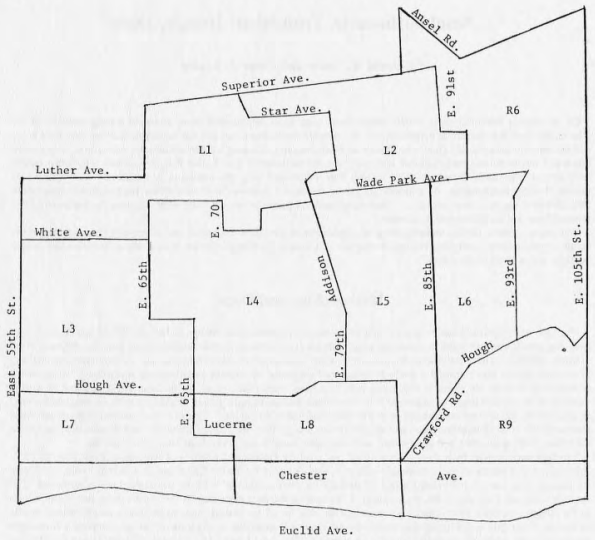

The data were derived from three sources. First, we used the Decennial Censuses of Population from 1910 to 1970. Information on a variety of socio-economic indicators was collected for the ten Cleveland Census tracts which comprise the Hough area, tracts L1 through L8 and R6 and R9 for 1940-1960. In 1970 the ten tracts were renumbered 1122 through 1128 and 1186 and 1189, respectively. (The map on the next page depicts the census tracts and major streets in the Hough area from 1940-1960.) We averaged the data for all ten census tracts to provide a neighborhood profile of Hough. Such data is published decennially by the Census Bureau and is available in the governmental documents section of most public or university libraries. A previous Cleveland researcher, Howard Whipple Green (1931), had already collected census tract data for 1910-1930, so we relied upon his published works for information about Hough during those years. Frequently neighborhood research can benefit in this fashion from work done previously by other investigators.

Second, since documents and reports issued by local, state and federal governmental agencies can provide invaluable insight into neighborhood change, we have examined a number of such reports in this study. These are intended to provide a more “qualitative” feel for the neighborhood than that provided by the aggregated census data. The reports reviewed included the “Summary of the Preliminary Plan for the Hough Community” and “A Report on the Preliminary Plan for the Hough Community,” both issued by the Cleveland City Planning Commission: “Urban Renewal: The Chapla Report,” published by the Cleveland Little Hoover Commission (1966); “Equal Opportunity in Suburbia,” published by the U.S. Commission on Civil Rights (1974); and the Report of the National Commission on Civil Disorders issued in 1968.

Finally, an additional qualitative “feel” for the neighborhood was provided by systematically searching three local newspapers (The Cleveland Press, The Cleveland News, The Plain Dealer) for material about Hough’s transformation.

Since time was limited it was not possible to examine all editions of the three newspapers for relevant material. We therefore confined our investigation to the ten years before and after the nineteen fifties, the decade of greatest neighborhood change. Our universe of newspapers thus covered a 30-year span from 1940 to 1970. This phase of the research was facilitated by the Cleveland Public Library, which maintains running newspaper files on various Cleveland neighborhoods. We began our investigation by ordering the material in the Hough file according to date and newspaper. If the file contained corroborating stories or accounts from at least two of the newspapers regarding the same Hough-related event, then the account was included in our data base. If, on the other hand, the library file contained only one newspaper account of a Hough event, and if we could not find any discussion of that event in one of the other newspapers during the week before or after the citing, or we could not corroborate the report with other data (e.g., public documents), then that single account or report was not included in the data base. In this way, we attempted to guard against journalistic bias and differential interpretation, and thereby increase the validity of our data. Since the study was being conducted some 15 years after the transition in question, the newspaper reports and accounts included in our material constitute a kind of “strategic substitute” for first-hand observation and interviewing.

The census data was used to pinpoint the period in which Hough underwent transition and to describe the nature and magnitude of the change. The qualitative data sources were explored to acquire greater familiarity with the Hough area and to isolate the configuration of factors that precipitated the change. Our familiarity with the Hough area was also based on the work experience in the area of one of the authors for a one year period in the late nineteen sixties.

The Site

Hough (pronounced “huff”) is a two-square-mile residential area located approximately two miles east of Cleveland’s Public Square. Fifteen minutes from downtown Cleveland by public conveyance and only minutes away from the cultural and educational facilities of University Circle. “Hough’s greatest asset,” it has been suggested, “is its favorable location.”[4] Following its annexation in 1872, Hough became a fashionable residential neighborhood that was described in 1910 as “the healthiest in Cleveland and with the best behaved citizens.”[5] Although its socio-economic standing began to change during the nineteen twenties and thirties, Hough was still a predominantly white, middle-to-working-class neighborhood at the time of the 1950 census. Within the next decade, however, Hough underwent a dramatic transformation. By the early nineteen sixties there had been a complete reversal in its racial composition—from 5 percent non-white in 1950 to 74 percent non-white in 1960. Furthermore, there were few remaining traces of its former upper-and middle-class socio-economic status. After a U.S. Civil Rights Commission investigation in the spring of 1965, for example, one of the commissioners related that the conditions in Hough were the “worst I have seen.” In the same spring, Hough was considered too great an insurance risk by Lloyds of London. In July 1966, the neighborhood exploded with a week of rioting. Occurring between the summer of Watts and the riots of Detroit and Newark, the eruption in Hough was classified as one of the worst the nation experienced during 1966. Time magazine concluded that “if ever a slum was predictably ripe for riot, it was Hough.”[6]

Why did this residential neighborhood, once regarded as one of the finest in Cleveland, deteriorate into a pocket of physical blight and human despair? What precipitated the sudden transformation of this formerly white, middle-class neighborhood into a black slum-ghetto? What were the major forces and social processes that wrought the change? If an ecological perspective is applicable, there should have been a number of “natural forces” underlying the change, such as the growth and piling-up of Cleveland’s black population. On the other hand, if a public-policy or power-conflict approach is applicable, there should have been certain real estate practices, public housing programs and the like playing a salient role in Hough’s transition. Was the sudden and dramatic change primarily the function of ecological forces? Or was it the result of a combination of both factors?

Reasons for the Transition

Although Hough changed most dramatically during the nineteen fifties (see Table 1), our analysis reveals that its emergence as a slum-ghetto can be traced in part to the impact of various forces and events that occurred several decades earlier. As one perceptive Hough resident pointed out, “The Negroes who moved in inherited conditions that existed long before they came.”[7] We thus begin with an examination of a number of predisposing factors which set up Hough for eventual deterioration and transition.

Myopic Planning. Of the major predisposing factors, perhaps none was more instrumental in circumscribing Hough’s future than its original design for a way of life not compatible with that of future generations. Emerging at the turn of the century as a suburban oasis of large, single-family homes housing Cleveland’s established well-to-do, provisions for population expansion, parks and playgrounds for children, and automobile traffic were not included in Hough’s early developmental plans. Streets were designed for the horse and buggy, making for congestion with the introduction and diffusion of the automobile. Park and playground facilities were quite limited, well below minimum planning standards. ln 1948, for example, the City Planning Commission called for 65 acres of play space in Hough, which then had only 12. This prompted the Cleveland News to observe that Hough was “in danger of collapsing because one vital factor is missing. There is not enough play space for those 15,000 children whose ages range from 5 to 19 years.”[8] By the end of the following decade, nearly 50 percent of Hough’s population was under 25 years, with the percentage under 14 years having increased from 17 to 34 percent (see Table 1). This 116 percent increase in the number of persons under 14 between 1950 and 1960, in conjunction with the growing number between the ages of 15 and 25, predictably had devastating implications for Hough’s already overtaxed and limited public facilities: the schools became overcrowded and understaffed; the parks and playgrounds became grossly inadequate, and the streets became ball diamonds.

Table 1

| Selected Demographic Characteristics for Cleveland and Hough, 1940-1970* | ||||||||

| – | Cleveland | Hough | ||||||

| Demographic Variables | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 | 1940 | 1950 | 1960 | 1970 |

| Population | 878,336 | 914,808 | 876,050 | 750,903 | 64,800 | 65,694 | 71,575 | 45,5222 |

| % Nonwhite | 9.7 | 16.3 | 28.9 | 38.2 | 1.1 | 4.9 | 74.2 | 93.0 |

| % White Collar | 35.5 | 36.3 | 35.3 | 36.6 | 47.1 | 42.3 | 22.2 | 21.8 |

| % Under 25 | 38.5 | 36.4 | 41.7 | 45.3 | 31.5 | 33.0 | 48.6 | 53.1 |

| % Unemployed | 12.7 | 5.5 | 7.5 | 5.4 | 11.4 | 6.3 | 14.2 | 11.7 |

| % Housing Units Overcrowded (1.0 + per person) | 12.1 | 10.1 | 10.3 | 6.9 | 12.3 | 11.3 | 21.2 | 13.5 |

| % Housing Units Substandard | 14.3 | 13.7 | 21.7 | a | 27.9 | 26.3 | 37.6 | a |

*Source: For 1940 figures, U.S. Census of Population and Housing: 1940, “Statistics for Census Tracts, Cleveland, Ohio and Adjacent Area,”(Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Priming Office, 1942). For 1950 figures, U.S. Census of Population and Housing: 1950, Volume III, Chapter 12, “Census Tract Statistics, Cleveland, Ohio and Adjacent Area,” (Washington. D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1952). For 1960 figures, U.S. Census of Population and Housing: 1960 Census Tracts. Final Report PHC (1)-28 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962). For 1970 figures, U.S. Census of Population and Housing: 1970 Census Tracts. Final Report PHC (1)-45 (Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1972).

a. The Census Bureau in 1970 omitted previously used measures of substandard housing.

Deterioration of Housing Stock. In addition to the limited public facilities and amenities, another potentially blighting influence inherited from the past was the age of Hough’s housing stock. Of all existing housing structures in the Hough area in 1959, 99.7 percent were built before 1939, and well over three quarters were constructed earlier than 1920. Thus, by 1950 Hough’s housing stock had aged as a unit, and little replacement housing was being built. The obvious consequence was that the future generations that moved into Hough inherited aging housing in need of repair.

Effects of the Great Depression. The Depression of the nineteen thirties hastened the decline of many residential neighborhoods, and Hough was no exception. It was adversely affected by the Depression in three particularly important ways. First, home upkeep and repair were postponed. Second, many families had to double-up or take in boarders, contributing to overuse of the housing stock. Third, the Depression accelerated the change from owner-occupied to rental status. Before 1930 Hough’s residences were predominantly single-family homes; by the early nineteen thirties only 36 percent of the homes were owner-occupied. The Depression thus initiated a process from which Hough would not recover: an increase in the number of absentee landlords and a decrease in the number of owner-occupied homes. In short, Hough had become a neighborhood of renters and tenants.

Effects of World War II. The social and industrial upheaval associated with World War II also contributed to Hough’s eventual transformation. With the wartime demand for labor came a massive infusion of blacks into the cities. During the period 1940-1950 Cleveland’s black population grew by 65,000, an increase of 76 percent. Although Hough’s black population rose from only 1 to 5 percent during the same span (see Table 1), the migration of blacks into Cleveland proper had future implications for Hough. The seeds were being sown for an intensive housing competition.

Also of significance were wartime housing policies, particularly the rent control program which undermined the incentive to maintain property and indirectly encouraged landlords to subdivide their apartments into smaller units. The net result was crowding, a decline in home and apartment maintenance, and an increase in the wear and tear on the aging housing structures.

The Piling-Up Process. The final predisposing factor rendering Hough susceptible to deterioration was what is referred to as the piling-up process: an increase in population without a corresponding increase in the amount of dwelling space. As already indicated, the size of Cleveland’s black population increased rather sharply during the nineteen forties. At the same time, however, there was no substantial increase in housing for blacks, as reflected by the fact that the level of room-crowding increased in 78.4 percent of the census tracts in which blacks resided during the forties.

This piling-up process was not unique to Cleveland’s black community in the years just preceding Hough’s radical transformation; it was also occurring within Hough itself. Between 1910 and 1950, Hough’s population increased by 25,000 without a commensurate increase in housing. By 1950 Hough’s population of 65,694 was living in an area designed to house fewer than 50,000. This increasing population density and housing congestion accelerated the deterioration of the aging housing structures. Thus, when blacks moved into Hough in the fifties and the population increased by nearly 6,000, the congestion and problems created by premature deterioration were compounded. By 1960 the percentage of housing units with more than one person per room nearly doubled; 28 percent of the housing units were also considered unsafe or in need of repair, as compared with only 8 percent in 1940. Even more significantly, by 1960 over one third of all Hough housing units were classifiable as substandard (see Table 1).

To the extent that a slum-ghetto is characterized by deteriorating and dilapidated housing densely occupied by a low-income or impoverished population, Hough had become or was on the verge of becoming a slum-ghetto by the time of the 1960 census.

Situational Factors and Contingencies

The four factors discussed above are considered as “predisposing” conditions. They influenced and circumscribed Hough’s socio-historical development, with the effect of rendering Hough susceptible to the transformation that it underwent in the nineteen fifties. These four factors are also quite adaptable to the ecological model of neighborhood transition. They point to an older neighborhood undergoing transition in terms of social class and housing quality. The fact that Hough lay only slightly northeast of a burgeoning black population, under increasing housing pressure because of massive in-migration of blacks, made it a natural target for change. Nevertheless, these factors do not sufficiently account for the suddenness and completeness of the transition. Nor do they adequately explain why thousands of blacks moved into Hough rather than into other nearby neighborhoods. To understand why such a sudden transformation took place in this locality, our analysis turned to the kinds of factors suggested by the power-conflict approach.

The power-conflict perspective argues that residential mobility is often forced, particularly for the poor and minorities. It contends that residential location is generally constrained and sometimes determined by factors other than a household’s financial situation and its housing and locational aspirations. This explanation seems particularly applicable to Hough. More specifically, our research suggests that however blacks might have felt about their move into Hough, the vast majority had little choice in the matter. The decision was made for them by the confluences of three major factors: urban renewal programs, a highly segregated housing market and the behavior of a number of realty companies and landlords.

Impact of Urban Renewal. Between 1954 and 1966 the city of Cleveland instituted six urban renewal programs. As was often the case with urban renewal programs throughout the country, the Cleveland programs were directed primarily at black neighborhoods. In fact, in Cleveland perhaps more than anywhere else, urban renewal came to signify black removal. The first project alone is reported to have displaced approximately 23,000 blacks, over one fourth of whom allegedly moved into Hough. This project, which was started in 1954, was followed by two other renewal projects during the second half of the fifties, one beginning in 1956, and the other in 1959.

Since there had been a reversal in the racial composition of Hough’s population during the nineteen fifties (see Table 1), it can be hypothesized that the urban renewal programs were responsible for a large proportion of the blacks who moved into Hough. Although there is some speculative support for the hypothesis, no direct data is available to test it. The Urban Renewal Department did not know where the majority of the dislocated families had moved. It is possible, however, indirectly, to assess the hypothesis with census data. Table 2 in the index presents the residential locations of Cleveland and Hough citizens in 1960 as compared with their residences in 1955. The data indicate that 79 percent of the 43,000 people who moved into Hough between 1955 and 1960 came from the central city of Cleveland. It is likely that most of these people were displaced by the three mentioned central city urban renewal projects. This conclusion is suggested further by Table 3, which indicates that 84 percent of the 1960-occupied housing units were moved into between 1954 and 1960, with the greatest influx occurring between 1959 and March 1960.

In light of these figures and the fact that, blacks began an accelerated migration into Hough around the time that the first renewal project got underway, there seems to be little question that urban renewal was instrumental in Hough’s transformation into a black slum-ghetto.

Housing Segregation and Discrimination. Those blacks displaced by urban renewal were confronted with a housing market in which their options were highly restricted in terms of the number, quality and location of housing units. Most residential possibilities were either too congested or dilapidated, as in the case of the Central area, or closed to black occupancy, as was the case with the bulk of Cleveland’s housing, which was off-limits to blacks during the nineteen fifties. This figure, which is consistent with findings regarding residential segregation in Cleveland that suggest that most blacks, including those uprooted by urban renewal, had little choice about where to live.[9] Their scant options were circumscribed by a rigidly segregated and highly discriminatory housing market.

Of the few residential areas in which blacks might locate during the nineteen fifties, Hough was one possibility. As indicated earlier, not only was it adjacent to several established and congested black neighborhoods, but its black population had already increased by several thousand inhabitants by 1950. Even more importantly, Hough had come to be defined as open housing for massive black occupancy by a group of investors, realtors and landlords, who were instrumental in precipitating the transition from white to black and in hastening the widespread physical deterioration of the neighborhood.

The Role of Realtors and Landlords. Seeing Hough as a golden opportunity to make a quick and sizeable profit, a number of speculators and realty companies bought up apartments and single-family homes during the first half of the nineteen fifties. In order to encourage and expedite the sale of property, some realty companies fostered a climate conducive to panic selling. Evidence of such “blockbusting” activities can be seen in the reaction of the Hough Area Council, which declared an open war on panic selling in June of 1955. As part of its unsuccessful effort, block meetings were conducted to calm residents and show them, according to the president of the Hough Council, “that a minority group moving into an area does not reduce property values. People who do not keep their places in repair are the ones who run down a neighborhood.”[10] In covering one such meeting, The Plain Dealer reported that “the meeting started with remarks about minority groups and ended with apologies and blasts at unethical real estate dealers.”[11] In a statement given to The Cleveland Press, the Assistant Director of the Community Relations Board related:

If you charged as much as $25 a week, the tenants would still take in other families to help pay the rent and your property would run down. So if you don’t charge as much as the traffic will bear, you’re cutting your own throat.[12]

Table 2

| Residential Mobility of Cleveland and Hough Residents Between 1955 and 1960* | ||

| _ | Cleveland | Hough |

| Total Population 5 years and older as of 1960 | 744,911 | 60,143 |

| % Living in Same House in 1955 as in 1960 | 47.6 (368,650) | 22.1 (13,303) |

| % Living in Different House in 1955 than in 1960 | 48.8 (377,979) | 72.8 (43,800) |

| % Living in Different House in 1960 came from: | _ | _ |

| Cleveland’s Central City | 76.3 | 79.1 |

| Other part of SMSA | 5.6 | 1.5 |

| The South | 7.7 | 11.8 |

| The North or West | 10.4 | 7.6 |

*Source: U.S. Bureau of the Census, U.S. Census of Population and Housing 1960 Tracts, Final Reports PHC (1)-28 (Washington, D.C: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1962)

Table 3

| Year In Which 1960-Occupied Housing Units Were Moved Into* | ||

| – | Cleveland | Hough |

| Total Occupied Housing Units as of 1960 | 269,891 | 20,912 |

| % Moved into Between 1958 and March 1960 | 33.9 | 56.0 |

| % Moved into Between 1954 and 1957 | 24.7 | 27.8 |

| % Moved into Between 1940 and 1953 | 27.8 | 12.6 |

| % Moved into 1939 or earlier | 13.6 | 3.5 |

*Source: Same as for Table 2.

The City Building Commissioner, however, saw it differently. Commenting on the attitudes of landlords and the exorbitant rents they charged, he observed that “the Hough area is a place where we’ve been working hard to help keep slums from spreading, but these landlords, charging rents that make people jam up, are undoing our efforts.”[13]

Attempting to exploit the market, some realty companies and landlords even responded with what we call “conversion mania.” That is, nearly any structure that was capable of subdivision was subdivided. Garages that had four walls and a roof were converted into dwelling units. Old mansions and homes were subdivided into rooming houses and tenements. In the midst of this mania, building code violations abounded. According to the City Building Commissioner, some landlords persistently “ignored building code regulations” while others “employed every trick in the book in an effort to avoid compliance with the code regulations.”[14] For example, in 1956 a realty company was charged with 41 violations in two houses and a barn which had been converted into 33 dwelling units. In one of the houses, which had been chopped up into 15 units, there were only two bathtubs, two toilets, and one shower for 15 families.

The Hough housing situation had become a complex of code violations, greedy conversion practices and exorbitant rents. A realty company manager explained it all in terms of good business:

There’s no sense kidding anybody. People invest to make money. If they buy Shaker property they may get a 10 percent return. In these buildings they must get 20 percent to 25 percent because it’s a risk investment due to rapid depreciation of property values in the area and high maintenance costs. It’s simply a matter of necessity for the investor to get his money out quicker.[15]

With such a hit-and-run attitude, it is little wonder, as a member of the Cuyahoga County Tax Appeals Board stated nearly 12 years later that “Hough properties had their heyday, their maximum values, in the middle of the nineteen fifties and have been slowly and steadily declining since.”[16] It is also little wonder that Hough changed so dramatically within the span of six years. The blockbusting and panic-fostering activities of some realtors promoted the idea that black occupancy hurts property values and thus accelerated the exodus of whites. The conversion practices, the code violations and the exorbitant rents made rapid deterioration an inevitable byproduct of black occupancy.

Those associated with the control and allocation of dwelling space in Hough during the nineteen fifties—the realtor and the absentee landlord—thus played important roles in the transformation of Hough into a slum-ghetto. The rapid growth of Cleveland’s black population since the fifties, coupled with the impact of several urban renewal programs upon black inner-city neighborhoods, provided the “pull.” The welfare and residential preferences of black citizens seem to have mattered hardly at all.

Summary and Conclusion

Like many other inner-city neighborhoods, Hough’s emergence as a residential area at the turn of the century rendered it susceptible to eventual deterioration and change. The impact of the Depression and the upheaval of World War II nurtured the seeds of deterioration and further prescribed the pattern of change.

The sudden transition of that particular neighborhood, however, is not adequately explained by such ecological factors as natural deterioration, the growth and concentration of Cleveland’s black population, and the piling-up process. Our findings indicate that other factors were also at work: namely, urban renewal and a group of profiteering landlords and realtors. Indeed, it seems clear that the suddenness and magnitude of the change were largely a function of the policies and actions of certain public officials, real estate companies, and investors. Nonetheless, some critics might take exception to this conclusion, arguing instead that the sudden transformation of Hough into a black slum-ghetto would have occurred “naturally” in the absence of urban renewal and profiteering landlords and realtors. We disagree for several reasons. First, proximity to an expanding and congested black community does not guarantee the eventual racial transformation of the area. It increases the probability of change, but does not make change inevitable. Second, there is no inherent connection between racial transition and physical deterioration. Third, even if Hough had undergone transformation without urban renewal, the change could hardly be called “natural,” for it would have been shaped in large part by racist housing attitudes and practices already in existence.[17] Finally, as long as racial discrimination remains prevalent in the United States, analyses of racially changing neighborhoods will be inadequate unless they consider such factors as the steering practice of realtors, the lending practices of bankers, and governmental housing programs and policies.

Although our findings are limited to one case, we believe that they are not peculiar to Hough. Admittedly, variations are to be expected among neighborhoods in the particular constellation of social, political and economic factors that affect change. But one is still likely to find that differences in power relationships in a neighborhood will greatly affect land use decisions and change. On the one hand, this assertion is not especially remarkable; other sociologists have also indicated that conflicting interests and differential power relationships are important determinants of land use change in urban areas.[18] On the other hand, it is remarkable to observe how power relationships have been ignored by many researchers traditionally interested in neighborhoods or community land use arrangements.

This is not to suggest that the ecological perspective is of little analytic usefulness for understanding such processes as neighborhood transition. To the contrary, we believe that the research being done by contemporary ecologists has merit, particularly in delineating the forces that structure the parameters of social action. Yet, if answers are to be provided to the question of why one neighborhood changes more drastically than others, the analysis must go beyond the ecologists’ reliance upon census data concerning land use patterns and change. More specifically, qualitative techniques and data sources must be used to gain greater familiarity with the social relations within and external to the community in question. When this is done then, as our findings reveal, one is likely to discover that the kinds of factors suggested by the power-conflict perspective play a central role in neighborhood transition and urban land use.[19]

Bibliography

Caro, R. A., The Power Broker. New York: A. A. Knopf, 1974.

Castells, M., The Urban Question: A Marxist Approach. Cambridge, Mass.: The MIT Press, 1977.

City Planning Commission, Summary of the Preliminary Plan for the Hough Community, Cleveland, Ohio.

City Planning Commission, A Report on the Preliminary Plan for the Hough Community, Cleveland, Ohio.

Cleveland Little Hoover Commission, Urban Renewal: The Chapla Report. Cleveland, Ohio: Government Research Institute, 1966.

Goodman, R., After the Planners. New York: Simon & Schuster, 1971.

Green, H. W., Population Characteristics by Census Tracts, Cleveland, Ohio, 1930. Cleveland, Ohio: The Plain Dealer Publishing Company, 1931.

Guest, A. M., & Zuiches, J. J., “Another Look at Residential Turnover in Urban Neighborhoods: A Note on Racial Change in a Stable Community,” American Journal of Sociology 77, (1971), pp. 457-467.

Harvey, D., Social Justice and the City. Baltimore. Md.: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1973.

——–., “Class-Monopoly Rent, Finance Capital and the Urban Revolution.” Regional Studies 8, (1974), pp. 239-255.

——–., “Labor, Capital, and Class Struggle Around the Built Environment in Advanced Capitalist Societies,” Politics and Society 6, (1978), pp. 265-295.

Molotch, H., “The City as a Growth Machine: Toward a Political Economy of Place,” American Journal of Sociology 77, (1971), pp. 468-471.

——–., “Capital and Neighborhood in the United States: Some Conceptual Links,” Urban Affairs Quarterly 14, (1979) pp. 289-312.

National Urban Coalition, Displacement: City Neighborhoods in Transition. Washington, D.C.: Author, 1978.

Pahl, R, Spatial Structure and Social Structure (Working paper no. 10). London, Centre for Environmental Studies, n.d.

Park, R. E., Burgess, E. W., & McKenzie. R. D., The City. Chicago, Ill.: the University of Chicago Press, 1925.

Rose, W. G., Cleveland, the Making of a City. Cleveland: The World Publishing Co., 1950.

Sumka, H. J., “Displacement in Revitalizing Neighborhoods: A Review and Research Strategy,” In Volume 2, Occasional Papers in Housing and Community Affairs. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1978.

Tabb, W. K. & Sawyers, L., (Eds.), Marxism and the Metropolis: New Perspectives in Urban Political Economy. New York: Oxford University Press, 1978.

Taeuber, K. E., & Taeuber, A. F., Negroes in Cities. New York: Atheneum, 1965.

U.S. Commission on Civil Rights, Equal Opportunity in Suburbia. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1974.

U.S. Riot Commission, Report of the National Commission on Civil Disorders. New York: New York Times Company, 1968.

Weiler, C., National Association of Neighborhoods Handbook on Reinvestment Displacement: The Public Role in a New Housing Issue. Washington, D.C.: National Association of Neighborhoods, 1979.

- A. M. Guest, et al., "Another Look at Residential Turnover in Urban Neighborhoods: A Note on Racial Change in a Stable Community" American Journal of Sociology, 77 (1971), pp. 466- 467. ↵

- By a black slum-ghetto, we refer to a residential area, usually within the inner-city, characterized by deteriorating and dilapidated housing densely occupied by a relatively low-income black population whose style of life and mobility are circumscribed by poverty from within and prejudice and discrimination from without. It is important to note that we use this concept advisedly. There is no perjorative [sic] meaning implied. Nor are we implying any causal relationship between race and living conditions. In fact, both the racial transformation of Hough and the accompanying structural deterioration of the neighborhood were a function of other forces described later in the paper. ↵

- H. Moltoch, "Reply to Guest and Zuiches: Another Look at Residential Turnover in Urban Neighborhoods" American Journal of Sociology, 77 (1971), pp. 468-471. ↵

- "Summary of the Preliminary Plan for Hough," (Cleveland: City Planning Commission, 1957), p. 1. ↵

- W.G. Rose, Cleveland: The Making of a City. (Cleveland: The World Publishing Co., 1950), and "Crowded Hough Everyone's Problem" in The Plain Dealer, Nov. 24, 1963. ↵

- "The Jungle and the City" in Time, 1966, p. 11. ↵

- "Crowded Hough . . . " ↵

- "Hough Playspots Needed" in Cleveland News, 1948. ↵

- Cleveland residential segregation scores for 1950 and 1960 were 91.5 and 91.3, respectively. This meant that approximately 91.5 percent of Cleveland's non-white population would have had to change their residential block in 1950 and 1960 in order to live in an unsegregated neighborhood. See Taeuber. K.E., et al., eds., Negroes in Cities (N.Y.: Atheneum, 1965). ↵

- "Hough Leaders Declare War on Panic Selling," Cleveland Press, June 3, 1955. ↵

- "Hough Council President Hits Property Neglect." The Plain Dealer. June 4, 1955. ↵

- "Negroes Charged $190 in Hough Area Suites as Whites Are Ousted" in Plain Dealer, June 29, 1955. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- The Plain Dealer, June 29, 1955. ↵

- Ibid. ↵

- "Inspector Seeks 41 Warrants," Cleveland News, Ap. 13, 1955. ↵

- That neighborhood or community change seldom, if ever, occurs "naturally" (e.g., in the absence of powerful interest groups and institutional actors) is further demonstrated by "redlining." This refers to the practice whereby a bank or savings and loan company refuses to make mortgage and home improvement loans to a community considered a "high risk" investment. In effect, redlining creates a self-fulfilling prophecy whereby a neighborhood with potential for subsequent decline (e.g., older housing stock) is refused the very money which could prevent the deterioration from ever occurring. One is hard-pressed to attribute anything "natural" to the outcome. Rather, it is the result of a deliberate banking policy. Recent revitalization efforts in larger cities also illustrate how decline can be arrested when banks reverse their red lining strategy and invest resources in a declining neighborhood. ↵

- See R. A. Caro, The Power Broker (N.Y.: A. A. Knopf, 1974) and C. W. Hartman, Yerba Buena: Land Grab and Community Resistance in San Francisco (San Francisco, Cal.: Glide Publications, 1974). ↵

- The complete version of this paper appears in the Journal of Applied Behavorial Science. Vol. 16, No. 4 (1980), pp. 459-481. The Journal of Applied Behavorial Science has given the Cleveland Heritage Program the right to re-print an edited version of the original paper. ↵