Part I. Neighborhood Studies

Neighborhood Studies

Edward Miggins

“Fellowship is life and the lack of fellowship is death” wrote English poet William Morris. For many people it is this feeling of togetherness that lies at the heart of what we mean by “community”—and distinguishes a community from any other social organization. This sense of “we-ness” derives from the very nature of a community, which might be loosely defined as a group of people united by common bonds, interests or standards of behavior. The family is the model for this kind of group.

Sociologists have identified several such groups united by common interests or lifestyles—“the ghetto,” “the rural versus urban way of life,” “the street corner society,” “suburbia,” “the organization man” or “the ethnic” or “blue collar” neighborhood. But a community can also have a territorial dimension. It can mean place as well as people.

A “community” can refer to the physical area where a group of people maintain their homes, rear their children, earn a living and conduct most of their important life activities.[1] In this sense, a community is said to consist of people with one or more common interests interacting within a limited geographical space. The people within such an area share not only “this or that particular interest, but a whole set of interests wide enough and complete enough to include their lives. The mark of a community is that one’s life may be wholly lived in it.”[2]

The Purposes of Community

A village, a town, a city, a state or a nation can each be thought of as a person’s community. The meaning or the term changes according to one’s frame of reference. A person might identify himself as a “Clevelander” when meeting someone from Atlanta, as an American upon introduction to a Russian or as a West Sider when encountering someone from the city’s East Side. But in certain basic ways, all of these “communities” are alike.

A community serves five major functions:

- socialization—the instillation of values and standards of behavior among members. An individual learns how to behave or accept the way of living prescribed by his or her society.

- social control—the exertion of influence to obtain conformity to a group’s norms. The local government, the police, the family, the church and the school are all important agencies which influence individuals to act according to a particular standard of behavior.

- economic welfare—the provision of a means of earning a livelihood by all owing people to participate in the process of producing, distributing and consuming goods or services. Modern communities often interact with each other—or depend on other agencies or locales—to meet this function.

- mutual support—the provision of the means to accomplish tasks that are too large for one person, such as the care of the sick, the elderly or the poor. Modern communities have transferred many of these functions, which traditionally belonged to the family, to public agencies.

- social participation—the fulfillment of a person’s need for companionship. The church, the home, volunteer service groups and many other social organizations fulfill this function.

For the community to exist, sociologist Roland Warren maintains, all five major purposes must take place within or near a definite geographical location.[3] But many of his peers have observed that the typical urban American works in one area, lives in another and socializes in still a different area. In recognition of this reality, some sociologists have advocated the concept of “the community of limited liability.”[4] A person’s activities often occur more in a context of different “people” networks with strong bonds of fellowship or unity rather than in special places.

The Neighborhood as a Community

The traditional feeling and concept of community as a “special place” has given way to the economic and social malaise of the modern city. Newspapers give daily reports of the crime and violence that is endemic to urban areas. The sad fact is that the complexity, impersonality and size of urban areas and their attendant social problems often undercut any sense of community. Louis Wirth and Robert Park, the pioneers of the Chicago School of Sociology in the nineteen twenties, defined “urbanism” as a way of life in which secondary, casual or transitory associations become the dominant mode of social interaction.[5] Although the modern city makes people economically interdependent, they define themselves and their relationships to others, according to Wirth, by their segmented social and economic roles. An urban person typically identifies himself by his occupation—the role he plays within a specific economic enterprise.

Urbanism, moreover, is not one way of life, but many. The modern American city is a social mosaic of different ethnic groups and lifestyles determined by age, occupation and social class. Sociologist Herbert Gans divided the population of a typical urban area into five distinct groups.[6] Each has a distinctive way of life that gives its members a sense of community: the cosmopolites, the unmarried or married and childless, ethnic villagers, the deprived, and the trapped or downwardly mobile.

The search for something beyond lifestyles around which to unite groups within the impersonality and complexity of a city has led urban planners, sociologists and residents to rediscover the importance of the neighborhood as a community. Lewis Mumford, the author of The Culture of Cities and dean of America’s urban theorists, advocated a return to an emphasis on the family and the neighborhood as the antidote to the disorder and the growing obsession with money, technology and power in modern society.[7] Mumford ‘s ideal neighborhood contains a diverse population of all ages and socioeconomic backgrounds. It would also offer a variety of housing styles—single, double and multiple—to accommodate the heterogeneity of residents, while a wide range of social spaces and facilities, within walking distance to reduce dependence on the automobile, would serve neighborhood needs. Others share Mumford ‘s viewpoint. After reviewing the history of the city from the ancient Greek city-state to its present-day form, Constantinos A. Doxiadis, a world renowned urban planner, concluded that the neighborhood was a “natural community” which could only be destroyed at great cost to mankind’s development.[8]

Of course, neighborhoods are still part of the human mosaic of most modern cities. New York ‘s Chinatown, Cleveland’s “Little Italy” and Boston’s “Beacon Hill” are distinctive places as well as ways of life. Their uniqueness flows from a number of geographical, cultural and socioeconomic factors. “Local areas that have,” according to sociologist Suzanne Keller, “physical boundaries, social networks, concentrated use of area facilities and special emotional and symbolic connotations for their inhabitants are considered neighborhoods.”[9] Neighborhood researchers, historians and sociologists are using a variety of methods to study communities.

The Social Survey

1. A social survey which systematically interviews a large number of people or a representative sample residing in an area is one way to study a community. First, the problem or issue behind the research must be identified. Second, the make-up of the population and the best method for selecting a representative sample of respondents must be ascertained. For example, if twenty percent of the study’s population is non-white, then approximately the same percent of a carefully selected sample must consist of non-white people. The researcher must then decide what information is needed from the respondents. The questions to be asked in the interview or questionnaire are based on this decision. The last step is the analysis and presentation of the data.[10]

Using this type of investigation, Charles Booth, the founder of the Salvation Army, published a seventeen-volume study of London between 1892 and 1896. In 1907, Paul Kellogg directed the Pittsburgh Survey that graphically illustrated the burden of what he described as “indirect taxation—levied in the last analysis upon every inhabitant of the city—of bad water, bad houses, bad air, bad hours.”[11] Other cities also applied the social survey to their problems.

In 1914 the Cleveland Foundation asked Allen T. Burns, a prominent social worker who had been involved in the Pittsburgh Survey, to investigate the city’s private and public welfare agencies. A year later, the Foundation sponsored a public school survey under the direction of Leonard Ayres of the Russell Sage Foundation. It released twenty five reports by locally and nationally prominent researchers. The Foundation later estimated that over seventy percent of its recommendations had been adopted by the schools. Its survey stands as the most comprehensive examination of a public school system in the history of American education. In 1919 the Foundation appointed Raymond Moley, a professor of political science at Western Reserve University and, later, a member of F. D.R.’s “brain trust,” to complete a survey of private and public recreational facilities. As the first director of the Cleveland Foundation, Moley helped to conduct a study of teacher training in 1920, and in 1921, under the supervision of Prof. Felix Frankfurther and Roscoe Pound, a survey of the city’s criminal justice system.[12] The Foundation’s efforts influenced other agencies and social-welfare organizations to utilize the survey as a basis for understanding their clients and the local community.

In 1932 the Cleveland Welfare Federation sponsored a detailed survey of Cleveland’s Tremont area. Two researchers, aided by a network of representatives from private and public social-welfare agencies and local institutions, investigated the relationship between young male adolescents and their community. The researchers discovered that Tremont had the highest population density of any neighborhood in the city.[13] Most homes that were originally built for single families contained two or more households. Of the one hundred and three young boys interviewed in the study’s sample—a representative cross section of their community—sixty three had worked at one time or another. Of the twenty six employed at the time of the interview, half were under the age of sixteen. Such early employment resulted in a high attrition rate for young boys from school and reflected the poverty of the area. The surveyor’s report recommended that social-welfare agencies should begin their work with an examination of the needs and backgrounds of their clients. It also proposed that community planning be based on a neighborhood approach.

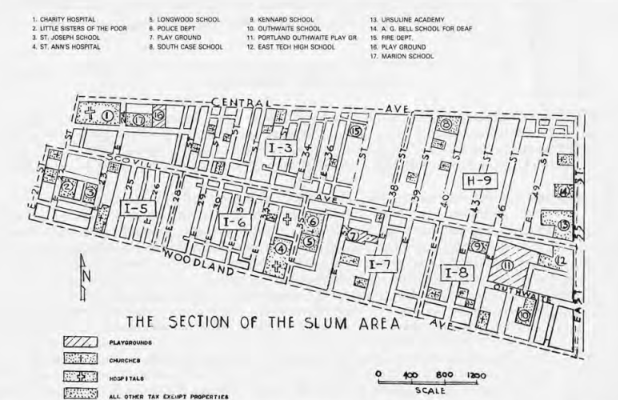

In 1934 the Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority published a report by Rev. Robert B. Navin on Cleveland’s lower Central-Woodland neighborhood. The survey documented this community’s disproportionate amount of crime, sickness, unemployment and social problems. By graphically illustrating the cost of maintaining private and public services in a deteriorated neighborhood (Navin put the figure at $1.75 million dollars more than what was generated by its real estate taxes),[14] this study prepared the way for a slum clearance project and the building of public housing in the following area:

The social survey is still a practical way to gather quantitative data on a population in a neighborhood. It can answer questions on the socioeconomic status, the standards of living, the use of community facilities and political preferences of the community’s members. It can be used to determine such things as the amount of social interaction or “neighboring” and the attitudes on different issues among community members. Such a survey can even be an effective means of dispelling myths about a community.

Researchers from Cleveland’s Cuyahoga Plan, advocates of open housing, have found, for example, that contrary to popular opinion, racially integrated neighborhoods do not necessarily lead to the lowering of real estate values. In 1980-1981, nine neighborhoods with a substantial black population in the city of Cleveland appreciated at a higher rate than the county median. There was almost no relationship between price appreciation and whether a suburban community was more or less than five percent black. Such integrated suburban areas as Cleveland Heights and Shaker Heights respectively experienced an appreciation of 31.8 and 29 percent between 1977 and 1981.[15]

The Participant Observer

2. The participant/observer is another method of analyzing a community. Here the investigator assumes a role within the area of study, enabling him or her to collect data first-hand on its internal structure or processes through participation in the community’s life. Direct observation, interviewing and the analysis is of documents are the techniques used to collect information. Herbert Gans employed the participant/observer method to study an “urban village,” of the West End of Boston, in the early sixties.[16] A neighborhood that had been declared by city officials as “a slum” targeted for urban renewal was revealed to be a thriving working-class area. Gans discovered that the lives of its Italian residents revolved around peer groups and the primary ties of the family household.

Carol Stack’s All Our Kin: Strategies for Survival of the Black Family was also based on personal observation of the extended kinship system of black families living in an urban area. Stack’s research answered such questions as “how people spend their time from the moment they wake up in the morning until they go to bed at night … what they do for each other, whether they exchange goods and services and how these exchanges are made.”[17] She came to see that the norms and values of the white middle class family have little meaning or validity for the extended social network of black family life.

Documentary Evidence

3. The analysis of historical documents and records is still another source of information on neighborhood life and development. An investigator should read the available histories of the neighborhood and the records of churches, businesses, voluntary associations and local historical societies. Such documents as naturalization papers, aliases, the federal census, marriage and birth records, property transactions and social welfare statistics can be invaluable sources of information.

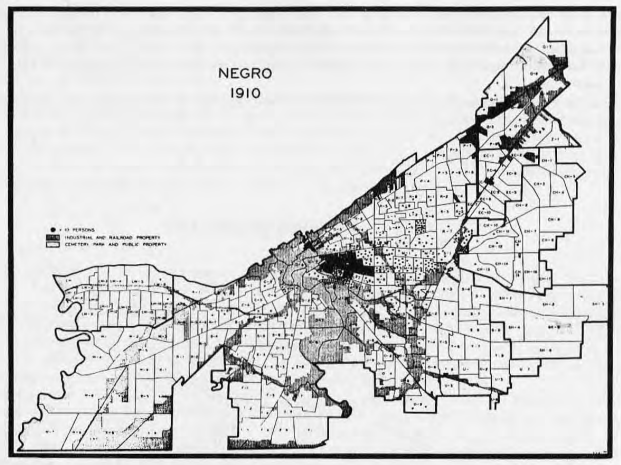

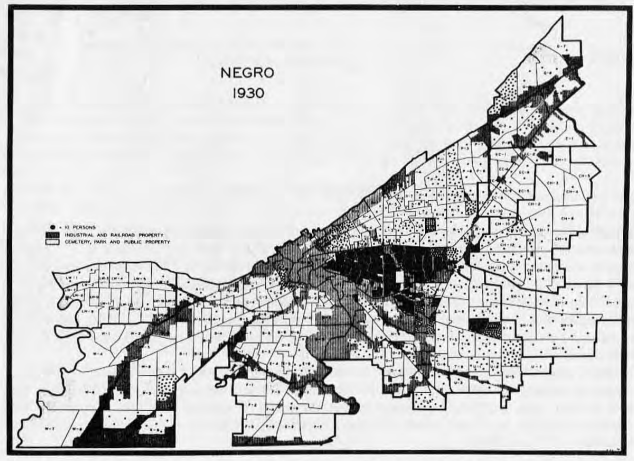

Utilizing the federal census, for example, a sociologist has found that segregation between Cleveland’s more recent immigrant or “ethnic” groups and other whites who had been living here for generations declined during the period from 1910 to 1960, but increased during the next decade. On the other hand, the black community’s pattern was totally different. In 1910 they were less segregated (60.0) than Italians (74.9). By 1960 blacks had become the most isolated group (90.0), but their segregation index had declined slightly by 1970—change attributed to the impact of the civil rights movement and fair housing laws of the nineteen sixties.[18]

Reports issued by governmental, social-welfare and health agencies can also be important sources of information, while photographs, local newspapers, personal memoirs and diaries can provide a graphic picture of daily life and events—as can oral history or personal interviews of reliable persons with first-hand information. Historian Daniel Weinberg used more than forty oral histories to analyze the life of Hungarians living in Cleveland’s Buckeye-Woodland neighborhood. “More than merely creating a parallel community to use their assimilation or acculturation into American society,” Weinberg found, “they created a context which functioned to thwart these processes–one in which Hungarian ethnic values, preferences and needs persisted and were preeminent.”[19] The study revealed how important such things as income, home ownership, naturalization and education of their children were for the Hungarian community as a means of achieving upward social and economic mobility.

4. Finally, the transactions and interrelationships that exist between a neighborhood and its surrounding area constitute important research materials that should not he neglected. Few neighborhoods exist in isolation from the rest of the city. And therefore such external factors as the provision of city services and the location of factories, businesses and transportation systems profoundly affect them. Modern society has made these relationships even more important to small communities.

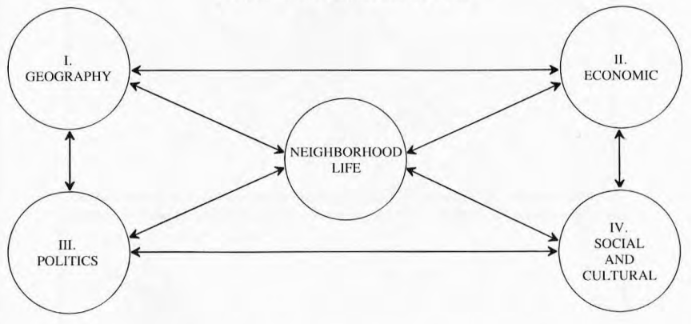

A select number of inter-related external and internal factors that influence the development of a neighborhood are considered in the following research model:

I. Geographical Factors

A neighborhood’s geography is an amalgam of physical and social boundaries. “People know, ” as sociologist David Morris has asserted, “when they are in their neighborhood and they know when they are out of it.”[20] Streets, industrial sites, transportation lines, parks, bodies of water or certain buildings can all be important features that separate an area from the surrounding community. A resident from Cleveland’s Tremont area recalled that in the eighteen eighties “we had but little contact with the rest of the city, either socially or in business.”[21] (The neighborhood is geographically defined by an eighty foot bluff overlooking the Cuyahoga River, Interstate highways 71 and 90, and Walworth Run.) Social and cultural traditions based on ethnic or socioeconomic criteria also make people look upon a neighborhood as a distinctive unit.

Both social and physical boundaries can change with the movement of different groups in and out of a neighborhood. Until the nineteen twenties, the eastern boundary of Cleveland’s black community was East 55th Street. But with the rapid growth or the size of the black population and the movement of Russian Jews and other groups who lived in the area between East 55th and 79th Streets, the black community (as shown in the following maps) dramatically expanded between 1910 and 1930:[22]

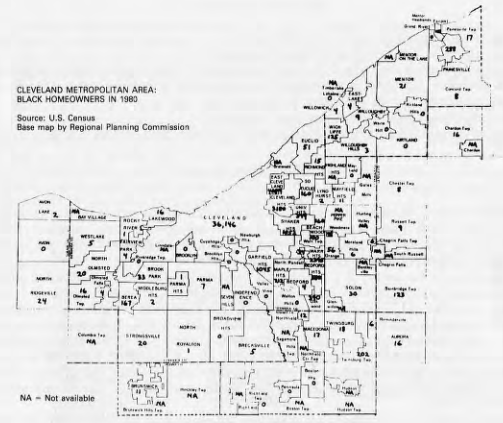

Overcoming the barriers of restrictive covenants in the deeds of white homeowners who wanted to prevent the sale of their homes to members of a different race (declared unconstitutional in the 1940s), the racist practices of realtors, and the relatively higher cost of housing in the city’s outlying areas, blacks have recently begun to join whites in the suburbs. Between 1970 and 1980 the black proportion of suburban households grew from 3.8% to 9.3%. But most of that increase was confined to a few communities.[23] If black families lived where they could afford housing, no suburb would be less than eleven percent black and Cleveland’s black population would be only twenty seven percent, rather than the present forty three percent. The Federal Fair Housing Act, instituted in 1968, has been only marginally effective in breaking down forced housing segregation in the central city and re-segregation in the suburbs, as shown by the following;

The location of a person’s residence or neighborhood is often used to determine his class or social ranking. Urban historians and sociologists have found patterns of residential segregation by occupation, nationality or race.[24] Cleveland ranks, as shown by the above map, as one of the most racially segregated metropolitan areas in America. To preserve or maintain their own status, people are likely to draw distinct boundaries between themselves and those considered lower in status. The latter, by the same token, are likely to blur the boundaries between themselves and the former. Sociologist Albert Hunter claims that one fairly distinct set of boundaries is that separating white and black residents.[25] As blacks move into a previously all-white community, racial prejudice leads whites to mentally redefine their boundaries. This process becomes more difficult when clear and distinct boundaries had been established and maintained in the past.

Such boundaries in what Hunter defined as the “defended neighborhood” are sometimes treated like international borders between foreign countries. To the south of Cleveland’s black residential area in the Central-Woodland neighborhood, the white ethnic communities along Broadway halted the advance of the black population. “When blacks tried to integrate the facilities of Woodland Hills Park located slightly to the southeast of the principal black section in the city,” according to historian Kenneth Kusmer, “it was members of these immigrant groups who fought against this change.”[26] The park became the site of racial conflict throughout the nineteen twenties.

Finally, the existence of minerals, the topographical elevation, the climate or scenic advantages can affect the identity or an area. What a community does with its natural resources is or equal importance. The development of a previously unused resource, such as oil or a scenic site, shapes the life of a community. And man-made changes in the natural environment such as the construction or highways, transportation lines or buildings can become as influential as a natural resource. The “concentration or buildings, land use and facilities and their impact on densities, dwelling conditions, the presence or absence of light, air and green open spaces,” according to sociologist Suzanne Keller, “give an area a spatial and aesthetic identity.[27]

Questions and Activities

- Describe the physical boundaries of your neighborhood.

- How, when, where and why have these boundaries changed?

- After interviewing residents about what they “think” are the physical and social boundaries of their neighborhood, consider the similarities or differences between their answers and the information obtained from the first question.

- Describe the topography, climate and natural resources of your area.

- What man-made changes have affected your local community?

- Draw a map of all major streets and transportation routes. To what areas are they connected or disconnected?[28]

II. Economic Factors

There are often enormous differences in the wealth and quality or life among communities in the same metropolitan area. An ethnic neighborhood situated next to an industrial site is very different from a bedroom suburb of affluent, transient people. Communities produce goods and services for their economic survival. How and why these products are produced can have important consequences for an area.

The tax base and level of the income of a community’s residents seriously affect its ability to afford services. In 1981 the greatest growth or local revenues, based on property valuation, for public schools in Cuyahoga County occurred in Solon (+10.0%) and Westlake (+10.8%)—outlying suburbs with fast growing residential and business areas. The fiscal disparity between Cleveland’s central city and suburbs is clearly demonstrated by the former’s assessed valuation of $43,660 per pupil versus suburban Cuyahoga Heights’ $436,752.[29] Today, most central cities in urban America face the task of providing services to a population that can least afford them. The demise or movement of industries and commercial businesses to new locations has further eroded the tax base of urban communities. It is estimated that Cleveland has lost over two hundred million dollars of its tax base over the past ten years for these reasons.

The economic life of most urban neighborhoods depends on the economy of the larger society or metropolitan area. The location or removal of a key industry which employs residents can often mean the life or death or a residential community.

Questions and Strategies

- Using the city directory, locate the major businesses and commercial establishments in your neighborhood on a map.

- How many local people are employed in these businesses? Who owns them? Where do the owners live?

- What markets do local businesses serve? What are the non-local ones?

- Interview a sample of residents to determine what businesses outside of your community employs residents.

- How, why and when has the local economy changed?

- According to the most recent census, what is the per capita income of residents? How many are unemployed? Retired? Union members? On welfare?

- If vital goods and services are not located in your neighborhood, where and how do residents obtain them?

- If you had to classify your neighborhood, which of the following would be the most appropriate description?

a. Bedroom community

b. Blue collar

c. Professional

d. White collar

e. Ethnic village

f. Other

III. Political Factors

The debate over how a community best governs itself goes back to colonial times. New England towns began the tradition of local self-rule in America. But towns as well as neighborhoods have been engulfed by urban sprawl during the last century. And as modern cities became more complex, local, state and federal governments assumed greater responsibilities. Greater efficiency and economy were also achieved through centralization. Independent school districts were, for example, consolidated for these reasons in Cleveland after the Civil War.

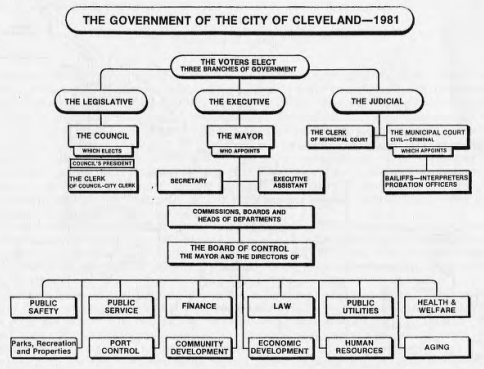

City governments like Cleveland’s developed and expanded their sewer, transit and water systems, police and fire protection, and a whole array of services to meet the needs of a rapidly growing population at the turn of the century. Cleveland’s rate of population growth between 1880 and 1920 was more than three times that of the nation as a whole, going from 160,416 to 806,368 people. Only Detroit grew more rapidly. To take advantage of the city’s services, outlying suburbs or neighborhoods voted in favor of being annexed to Cleveland. It wasn’t until the nineteen twenties, that wealthier suburbs with tax bases capable of providing equal, if not better, services resisted annexation and control by the city of Cleveland. The following is its present organizational structure:

City governments have traditionally taken the form of a strong council/weak mayor, strong mayor/weak council, or a city manager system. In 1921, the citizens of Cleveland voted in favor of the managerial form, but the experiment lasted only until 1931. The New Deal programs of the thirties began a lasting relationship between the federal government and municipalities like Cleveland. The federal government worked with cities to organize economic and social-welfare programs to alleviate the burden or the economic depression of the nineteen thirties. The Great Society programs of the nineteen sixties and, more recently, revenue sharing and Urban Development Block Grants continued the relationship established during F.D.R.’s presidency. Cleveland presently receives federal subsidies totalling [sic] over fifty million dollars per year.

Another major change has been the growth of special government agencies. By 1976, fifty nine of these agencies employing 16,000 full and part-time staff with an annual budget or over one-quarter of a billion dollars existed in Cuyahoga County.[30] Not subject to the direct control of the electorate, most were formed because of the inability of existing local government to deliver such necessary services as water, transit, sewer, recreation, health, welfare or education.

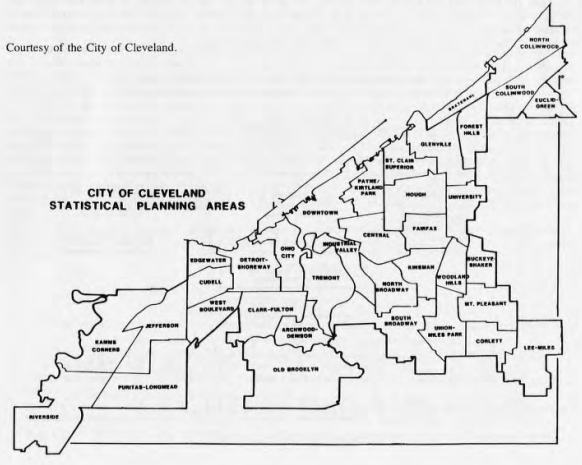

Advocates of neighborhood self-government argue that too much power remains in the hands of city hall. The clash between neighborhoods and city hall or downtown interests has a long history in urban America. Like other advocates of political decentralization, some people believe that the control of city services belongs at the neighborhood level. Cuyahoga County Common Pleas Court Judge Burt W. Griffin has recently proposed the creation of a federation of “sub-cities” with populations ranging from 10,000 to 60,000 people to control the resources and services of local government.[31] These are the areas or neighborhoods that are presently served by the city’s planning department:

The neighborhood or local area, in Robert Wood’s classic phrase, is a “Republic in miniature.”[32] Supporters of local power believe that the “importance of the neighborhood begins with the importance of citizenship. To be a citizen is to participate in civic affairs . . . To simply live in a place and not participate in its civic affairs is to be merely a resident, not a citizen.”[33] Although neighborhoods do not yet enjoy the degree of political power advocated by proponents of decentralization, they still play a vital role in a community’s political life. Since the nineteen sixties, the federal government has required cities to include neighborhood participation in such programs as urban renewal and revenue sharing. Even more importantly, urban planners and local leaders have gradually come to recognize how important neighborhood vitality is to the solution of deeply rooted social problems and to the success of local social-welfare programs.

“The way things are done”—the political traditions of a local area—continue to influence the life or a community. On the neighborhood level, the outcome of political decisions is often decided by individuals who may not hold political office. Such a position of power is often held by the “ward boss,” who controls the distribution of patronage and services from city hall in return for the delivery of votes from his area. An analysis of both the informal and formal processes of political life is a complex but exciting task for the neighborhood researcher.

Questions and Strategies

- List and describe the governmental units that serve your community. (Include parks, sewer systems, schools, libraries, transit or other special districts, and local governmental units.)

- What is the formal structure of your local government? Of your judiciary?

- What are the sources of revenue, legal authority and services of local units of government?

- How, when and why has the system of local government changed?

- Which persons or groups in your neighborhood have the greatest influence in local government?

- Interview local residents to find out whether they perceive conflicts between their neighborhood and the local government. How are they resolved?

IV. Social and Cultural Factors

As a social and cultural system, a neighborhood is a geographical cluster of persons with similar cultural and socioeconomic backgrounds. Neighborhood sociologists have debated whether an individual’s own characteristics (such as social class and ethnic background) or institutional and community norms have a greater impact on human behavior. Urban ecologists have shown how such things as the distance from downtown and the allocation of space are intimately connected with a neighborhood’s socioeconomic mixture, ethnic composition, age and crime rate. On the other side of the coin, participant/observers have analyzed how the norms and lifestyles of different subcultures have shaped neighborhood life. Both viewpoints taken together often become the most satisfying basis for interpreting social behavior. For example, a study of the Norwegian community in New York City revealed that this group could maintain “the things they valued only by retreating from the inexplicable development of the city to new territory.”[34] The community’s repeated relocation, in other words, was not only connected with the growth of the city and the limitations of space but also with its cultural norms and values.

People are often drawn to a neighborhood because of their preconceived ideas about its socioeconomic and cultural characteristics. In most metropolitan areas affluent neighborhoods, such as Cleveland’s Shaker Heights or Rocky River areas, are located in outlying, suburban communities. The poor and the elderly are left in what the Chicago School of Sociology described as the “zone of transition,” the neighborhoods close to the downtown, commercial-business district.[35]

A neighborhood’s norms and cultural traditions can, however, influence the behavior of new residents, for the social structure of a community exists independently of particular individuals.[36] Generations can come and go without disrupting the traditional patterns of interdependence that characterize a particular community. Sociologists have found, for example, that neighborhoods have retained similar rates of juvenile delinquency for several generations, suggesting that neighborhoods have the potential to transmit subcultural values.[37]

Even gossip among neighbors contributes to the life of a community by defining its membership and creating a sense of group identity. It eases the strain of competition and prestige. “The internal struggles within the group are fought,” according to Max Gluckman, “with concealed malice, by subtle innuendo and by pointed ambiguities.”[38] “Putting down” someone who is viewed as an ambitious “climber” or as a threat in some other way to the community preserves the homogeneity of the community. By scandalizing or lowering the general opinion of the person who challenges or differs from the group’s norms, the community maintains the general equality of the group—no matter how mediocre.

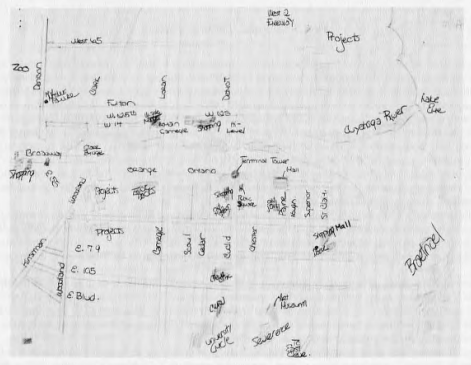

Urban residents reduce the complexity of the city through the use of mental images or cultural symbols for different places and neighborhoods: “Behind the ‘rational’ activities of the realtor or the burglar,” for instance, “there stands an intricate structure of assumptions about how the city is carved into separate pieces and why these units persist, change or become different from one another.”[39] A reasonable approach to urban life depends on a menial map of its structure and the way different features of the environment have determined that structure. It has been found that people structure their image in terms of five different elements:

- paths—the channels or routes that the observer uses

- edges–the linear elements that serve as boundaries between areas—such as shores, railway lines, walls and edges of developments

- districts—the medium-to-large sections that have a common identifying character

- nodes—the strategic spots, such as a street corner hangout, an enclosed square or a crossing, that help organize a district

- landmarks—simply defined objects, such as a building, a sign, a store or a mountain which are closely identified with an area.[40]

None of these elements exist in isolation in people’s minds. Districts are structured with nodes, defined by edges, penetrated by paths and marked with landmarks. These elements may overlap, but some will be psychologically more dominant than others. The following is a mental map of Ihe Cleveland area drawn by a student at the beginning of a course in American Studies at Case Western Reserve University.[41] What has been left out is almost as important as what is included in someone’s image of a city or neighborhood:[42]

Mental maps of a city or neighborhood can change as a person’s knowledge or awareness is enlarged; in reality, communities or locales can change. Cleveland’s Euclid Avenue, known as Millionaires’ Row in the eighteen nineties, had become the home of commercial establishments and boarding houses by the nineteen thirties. Such ethnic areas as Cleveland’s “Little Italy” or New York’s Chinatown –regardless of the changes that occurred in them—have evoked symbolic imagery and similar sentiments over many generations. Some neighborhoods, such as Cleveland’s Fleet-Broadway neighborhood, have even consciously attempted to retain an older image. Despite the movement of many older ethnic families to the suburbs and the arrival of Appalachian residents, this area has recently designated itself as a “Slavic Village.” Polish and Czech residents see this name or image as symbolic of both the neighborhood’s renewal and of their cultural roots in the area. “Not only do symbols of community reflect or refer to reality, but, like symbols generally,” according to one interpretation, “they may serve to define and create reality.”[43]

The symbolic neighborhood represents a set of cultural values both for the residents and the larger community. Values and norms are also expressed through “the neighboring role.” Such social amenities as mutual aid, borrowing food or tools, informal visiting and exchange of ideas and advice are found in every neighborhood. In some areas, particularly in the “ethnic village,” the roles of friend, relative and neighbor overlap. But the frequency and quality of social interaction varies according to the socioeconomic and cultural background of a neighborhood’s residents. It is the task of the neighborhood researcher to find the continuity as well as to describe the change in an area’s social system and cultural traditions.

Questions and Strategies

- Use the census or a sample of people in your neighborhood to determine the average age, social class, educational level and nationality background of residents.

- Is the demographic profile of your neighborhood typical of your region?

- Where is the greatest concentration of residents? The smallest?

- Survey a sample of residents to determine where they lived before their present residence. How long has the average householder lived in the neighborhood?

- After observing or interviewing neighborhood people, what would say is their level of “neighboring” or social interaction? Among different groups? With outsiders?

- With the help of the city directory and the telephone book, locate schools, churches, and nationality organizations on a map. What styles of architecture are used in their buildings? In residences?

- What role do the above institutions play in neighborhood life?

- What kinds of recreation exist? Are public facilities adequate? What are the private forms of recreation?

- How do the residents describe their neighborhood?

- What kinds of family households exist? (Nuclear family? Single parent? Extended family or several relatives living together? Boarders?)

- What cultural traditions are strong within family life? What are the similarities and differences among different nationalities, races, or income groups? What kinds of folklore exist in the community?

The Ethnic Roots of Cleveland’s Neighborhoods

Ethnic groups played a major role in the formation and continuation of Cleveland’s neighborhoods. “The Cabbage Patch,” “Warsawa,” “Chicken Yard,” “Dutch Hill,” “Big” and “Little Italy,” “Goosetown,” “Whiskey Island” and “The Angle” were the colorful names of Cleveland’s ethnic communities around the turn of the century.[44] Nationality groups built churches, schools and voluntary associations to help newcomers adjust to the often painful realities of the industrial city. Faced with the difficulty of not being able to speak English and finding Cleveland far different from the rural village or small towns of the Old World, immigrants molded their life around familiar institutions. By the nineteen twenties over 200,000 Clevelanders were attending nationality churches and over twenty nationality newspapers existed in the city.[45]

Ethnic neighborhoods gave foreign-born immigrants the time and resources to adjust to a new environment. Often located near the Flats and within walking or short commuting distance of jobs, they contained inexpensive housing and stores which specialized in ethnic foods. Fraternal organizations, such as Unity (1905), a Serbian Benevolent Society, or the Council Educational Alliance (1897) and the Hebrew Free Loan Society (1905) of the Jewish community, gave mutual aid and support to foreign-born residents.[46] Fraternal organizations provided insurance, not available elsewhere at the turn of the century, for old age, accidents, sickness, or death.

The heavy influx of immigrants caused the older residential areas of industrial cities to resemble a social mosaic. Newer groups displaced older ones. The Irish and Germans of New York City’s Lower East Side, for example, were followed by Russian Jews and Italians by the turn of the century. But rarely did ethnic neighborhoods or ghettos, with the exception of the black community, become totally homogeneous or isolated from the rest of society. Although historians have found that immigrant newcomers moved away from their areas of settlement within a relatively short period of time, their churches, fraternal halls and businesses often maintained the ethnic identity of a neighborhood after their immediate departure but also eventually moved from their original location.

Often ethnic institutions as well as churches relocated to remain close to their groups as they moved away from the downtown core of the city. Ownership of buildings changed hands as different groups arrived or left an area. St. Joseph’s Church, located at East 22nd and Woodland Ave., was successively used by Germans. Irish, and Italians. Its parish school now serves the children of black residents in the area. The B’nai Jeshurun, a temple located on East 55th St. which originally served Cleveland’s Conservative Jews, became the black community’s Shiloh Baptist Church. Such changes reflect the constant ebb and flow of waves of immigration and migration throughout the city’s history and development.

The second generation of European immigrants moved to the suburbs for a variety of reasons. Some feared the arrival of blacks and other minority groups. Another motivation was the desire to own newer homes with larger lots and easier access to the jobs, businesses and stores which had also moved to suburbia. Many wanted to escape the traffic congestion, polluted air and fiscal problems of the central city.

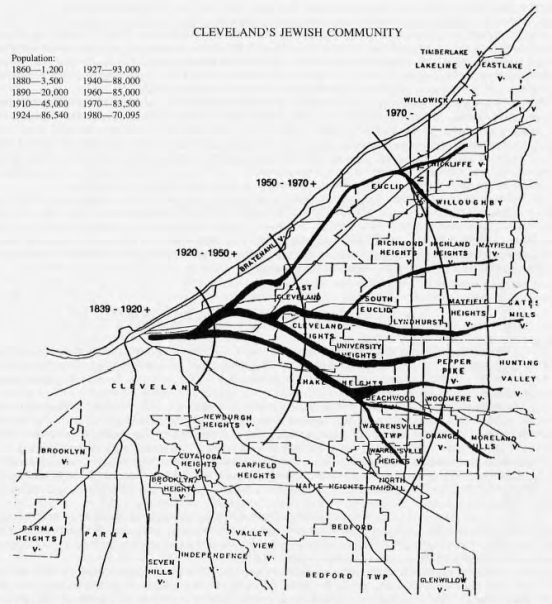

The pattern of settlement and movement or re-location of different groups in new neighborhoods is not random or accidental.[47] Confined by the barriers of white hostility to their ownership of homes in non-integrated areas, Cleveland’s black community, for example, primarily followed in the footsteps of Jewish residents. Ethnic corridors are the paths along which different groups travel as they move to a new area. Many of the Polish and Ukranian residents or their descendants who left the Tremont community traveled in the direction of West 25th Street and eventually settled in Parma, a West Side suburb. The Jewish community—one of the city’s most geographically compact groups—moved from its original home in the lower Central-Woodland neighborhood along major transportation arteries that led in an easterly direction as illustrated by the map on the next page.

Blacks from the American South answered Cleveland’s need for additional workers after World War I and immigration restriction laws drastically reduced the supply of European laborers. The Home for Aged Colored People (1896), the Phillis Wheatley Association (1913), Karamu (1915), the National Urban League’s Negro Welfare Association (1917), and, above all, churches of different denominations, often transplanted from the South, attempted to meet the needs of the burgeoning black community.[48] The black population expanded from 8,448 in 1910 to approximately 72,000 by 1930—a growth rate eight times faster than that of the white community. By the 1960s over 200,000 blacks lived in Cleveland.

The arrival of Appalachians, Asians, Puerto Ricans and other Spanish speaking groups from Latin America immigrating to Cleveland added to the city’s ethnic diversity. The Appalachian Council, the Chinese tong or family associations and the City Hall’s Office of Hispanic Affairs and the San Juan Bautista Catholic Church were among those organizations which served the needs of these groups. Like their European predecessors, the newest immigrant and migrant groups were helped by the city’s social settlements.

Social Settlements

Since the last decade of the nineteenth century Cleveland’s social settlements have provided important services to different neighborhoods and ethnic groups. In 1898 George Bellamy, a graduate of Hiram College, opened Hiram House, originally established two years earlier in the Flats area of Whiskey Island, to serve the needs of the Lower Central-Woodland Neighborhood—primarily an area of Russian Jews, Italians and blacks. Influenced by the social gospel movement and supported by wealthy businessman Samuel Mather, Bellamy and his fellow social workers developed a variety of educational, cultural and recreational programs. The settlement espoused the following: “To improve neighborhood conditions, to be true neighbors to these many groups, to help interpret America to them, to give them useful activities and wholesome recreation and to help them adjust to their environment.”[49]

Another example was Merrick House, established by the National Catholic War Council in 1919 to serve the Tremont area. As part of a post-War reconstruction program, it provided a day nursery, a summer vacation school, classes in sewing, shorthand, woodwork and cooking, and social or educational clubs.[50] By the nineteen twenties, almost a dozen settlements were attempting to improve the environments of Cleveland’s neighborhoods. As the latter changed, social settlements or neighborhood centers provided new and different programs.

Merrick House adapted, for example, to changes in the Tremont area. It helped residents in the 1930s to form the Tremont Area Council, the first community action civic association.[51] During the ’60s this settlement became a center for community organizations during the era of “the war on poverty” and “Great Society” programs. It became a forum for different groups attempting to organize the community and staffed resident associations. In February, 1976, Merrick House organized a forum around the theme of “What Does Tremont Want to Look Like in Five Years?” to develop a sense of direction among groups and residents in the community. The Tremont-West Development Corporation was organized for community action and support on such issues as housing rehabilitation, arson and crime.

Another example of a settlement changing to meet the needs of its community is the cooperation between Alta House, originally established with the help of John D. Rockefeller in the Murray Hill district or “Little Italy” in 1900, and citizens who wanted to control social conflicts and crime.[52] After holding a public meeting to discuss this issue, Alta House recently helped to organize a Community Dispute Settlement Project in which cases would be referred for mediation. Finally, the Collinwood Youth Development Center has alleviated tensions in its racially tense neighborhood by offering a wide range of services to young people.

The Deterioration of Urban Neighborhoods

Today, the efforts of Cleveland’s neighborhood centers are coordinated by the Greater Cleveland Neighborhood Centers Association, formed as the first clearinghouse of its kind in 1963.[53] Despite the programs and resources of

private and public community organizations, the city’s neighborhoods have deteriorated as the city’s population plunged from 914,808 in 1950 to 560,000 in 1980.

The neighborhoods of urban America were often overlooked or neglected after World War II. Helping to build suburbia and highways that accommodated the exodus of people and industries elsewhere, the federal government played a major role in the deterioration of the central city. Even efforts at rehabilitating such areas had an opposite effect. The government’s urban renewal program of the 1960s, for example, aggravated the problems of overcrowding and blight in the remaining communities. By 1968 it was reported that 4,255 dwelling units had been demolished but only 2,000 units built to replace them as a result of Cleveland ‘s participation in this program.[54] The displacement of residents to other neighborhoods, as illustrated in this Guide’s article on the Hough area, was a major factor in their deterioration.

The influx of poor people—migrants from the American South and Puerto Rico and immigrants from Latin America—and the night of more affluent residents to the suburbs or other areas of the country has profoundly affected Cleveland’s central city. It was left “with a predominance of households with low educational attainments, and low incomes” and a disproportionate amount of poverty, crime and delinquency.[55]

Approximately twenty percent of Cleveland’s families receive Aid to Families with Dependent Children and one-sixth have incomes below $2,000 per year. In the 1960s the city lost twenty five percent of its families with incomes below above the median for the Standard Metropolitan Statistical Area. In 1973, the per capita income in the region, not including the central city, was $6,750 or fourteen percent above the national average. Residents in the city had a per capita income of $3,160 or thirty seven percent less than the national average. In 1977 the unemployment rate of 11.5 percent was also higher than the rest of the nation. Among young black males the rate was 38.8 percent.[56]

As Cleveland’s population, economy, and per capita income drastically declined in the post-war era, its surrounding suburbs gained approximately two hundred thousand residents and one hundred and fifty one thousand jobs between 1960 and 1970. Like other suburban areas throughout America, Cleveland’s outlying districts provided housing and jobs for many new households but have maintained controls over the kinds of families who can live there through zoning ordinances. Such requirements as one acre per family, a large minimum floor space or number of bedrooms, the prohibition of public housing or multi-family dwellings and the maintenance of vacant land for commercial development have constructed walls around suburban areas against low income and minority families. In 1980 the average price of a single family, suburban home was $71,209, far beyond the resources of low income households.

Racial prejudice still exists as another barrier. The federal district court has found, for example, the city of Parma guilty of overt racism against black homeowners and has mandated a program of fair housing for that community.

Sections of Cleveland’s housing market in the central city collapsed in the 1960s and 1970s. The city’s population declined by over 125,000 (21,000 households) and the housing stock fell 18,000 units between 1960 and 1970. Between 1975 and 1979, 8,044 homes—of which over fifty percent were multi-family—were demolished. Of the 2,168 units that were constructed during this period ninety three percent were for the elderly. The growth of low income families resulted in a demand for poor quality housing, a decline in constructing new dwellings and under-maintenance of rental properties. Between 1967 and 1971 three houses were abandoned each day for a total of 3,475 units.[57] Public housing—the majority of which was built before the war—also suffered from neglect and decline.

The Neighborhood Movement

The neighborhood movement that emerged in the 1970s fought against public apathy and neglect. Social philosophers and civic-minded individuals increasingly recognized the importance of neighborhoods as small-scale communities that provided an alternative to the alienation and impersonality of mass society and modern bureaucracies. As Karl Hess stated in Dear America: “The human megaopolis and the corporate state that nurtures it are the exact opposite of everything that is local, humanistic and human in scale.”[58] Interested in the preservation of America’s multi-cultural heritage, others called for the maintenance of ethnic communities.

Advocates of neighborhood revitalization pointed to the economic benefits—particularly as the price of energy and new construction skyrocketed in the 1970s—of restoring and preserving older areas in the central city. Others saw themselves as part of America’s deep-rooted, democratic tradition of volunteerism and interest group politics.[59] More down to earth was the agenda of neighborhood activists who fought against banks, utilities, insurance companies and governmental agencies.

Founded in 1968 through the pioneering efforts of the recently deceased Sister Henrietta, a Catholic nun from Our Lady of Fatima Mission, the Famicos Foundation has helped to rehabilitate or build approximately two hundred homes in Cleveland’s Hough area. It has been funded by a consortium of private individuals, the Cleveland, Gund and St. Ann’s Foundations, the Hugh O’Neill Charitable Trust, private corporations and Cleveland’s Department of Community Development. It has helped other non-profit housing groups to utilize the Famicos’ strategy; namely, to acquire abandoned dwellings, FHA foreclosures, or other kinds of low cost houses for rehabilitation. Contractors are hired to bring the dwelling up to code but the family acquiring the house must invest funds or “sweat equity” to complete the rehabilitation process. Famicos has recently worked with a private developer and city hall to secure over two million dollars from the federal government’s Urban Development Action Grant program to develop Lexington Village, an apartment complex for moderate income people in the Hough Area.[60]

Organized by the Lee-Harvard Community Association in 1968, the Harvard Community Services Center developed a variety of programs for the people living in this southeastern neighborhood of Cleveland. Since its inception it has been under the direction of Rubie J. McCullough, who had formerly served as a staff member of the Phillis Wheatley Association for twenty three years. Based on the philosophy of providing services for what the local community needs, the Center instituted day care, after school and tutorial programs for young children and adolescents, a nutrition site for the elderly and a summer camp. It is presently attempting to coordinate the efforts of local agencies which serve the neighborhood in order to develop more effective programs and solutions to community problems.[61]

Supported by the Commission on Catholic Community Action and representative of one hundred and thirty five community groups, Cleveland’s Buckeye-Woodland Community Congress was organized in 1975. It confronted the problems of housing deterioration, crime, racial conflict, disinvestment and white flight from this former center of the Hungarian community. Arter a survey found that banks systematically “redlined” or refused mortgages to home buyers in this neighborhood, the congress was instrumental in passing one of the strongest laws against such practices. It also attempted to change the negative image of the neighborhood and harmful practices among real estate firms. The congress formed a development corporation that worked with four local banks in providing funds and services to arrest deterioration. Under this program vacant homes are purchased and rehabilitated for re-sale. The Buckeye Evaluation and Technical Institute was developed to administer energy audits of private homes and commercial businesses. By 1982 the congress reported that its efforts had brought more than nine million dollars into the area and had helped to increase property values by twenty percent over a two-year period.[62]

In 1975 Patrick Henry, the Director of Cleveland’s Community Development Program, organized Neighborhood Housing Services to provide a similar program. Based on the belief that residents, financial institutions and city hall could work together to save older communities, Neighborhood Housing Services (N.H.S.) began its first project on the city’s near West Side—an area that mainly contained elderly residents of older ethnic groups, Hispanics and Appalachians. Funds were solicited from savings and loan associations, commercial banks, the George F. Gund and Cleveland Foundations, the Greater Cleveland Growth Association and the Junior League. Grants from the city’s Community Development Block Grant Fund helped to repair and improve streets. Federal funds from Ohio’s Home Weatherization Program were used to insulate houses. Approximately two hundred and twenty homes have been rehabilitated and forty eight percent of the target area’s residences have been brought up to code. Finally, through a Home Ownership program, N.H.S. counsels and assists residents—of whom many were former renters—to purchase homes.[63]

Providing services and job training is another strategy for re-developing residential areas. Neighborhood associations and councils contend that they can deliver services as well as, if not better than, publicly subsidized bureaucracies and, additionally, provide job training and experience for local residents. Assisted by a loan from the Ford Foundation and administrative support from the Gund, Cleveland, and Ford Foundations, five neighborhood organizations (Glenville, Tremont, St. Clair, Broadway and Detroit Shoreway) have recently organized a weatherization program for low and moderate income residents. Supported by the city’s Department of Community Development, they can provide up to four hundred and fifty dollars for low-income households’ weatherization projects. City hall has also worked with Lutheran Housing, the Ohio Public Interest Campaign, East Ohio Gas, and the five organizations to hire neighborhood residents to perform energy audits of houses.[64] The St. Clair area has a recycling center that not only conserves materials and physically improves the neighborhood but also provides jobs for residents. The re-development of a neighborhood can be a vital ingredient in the economic health and progress or an urban area. An equally important step is the formation of a national network among neighborhood groups and city halls for the incorporation of their concerns as a priority of the federal government.

The Recovery of the City

Private and public efforts at revitalizing and maintaining older neighborhoods have to counteract the prevailing pessimism surrounding the future of older industrial cities. The fate of urban neighborhoods is inextricably bound to the health of the city and the national economy. The decline of population and industry, the disparity in fiscal resources between the central city and suburbia and the growing demands for services among the elderly, minority and low-income groups are at the bottom of today’s problems in central cities like Cleveland.

Despite the severity of these conditions, Paul R. Porter, the author of The Recovery of American Cities, believes that an urban renaissance is possible: “If American cities do not recover, it will not be because the effort is too much for us . . . The idea is no bolder than the Marshall Plan . . . If we miss the beckoning chance to restore our cities to health, it will be because of ourselves—something in our present view of things or in our spirit that sets us widely apart from the generations of Americans who came before us.”[65] He contends that the decaying districts of the central city should be made attractive enough to compete with the suburbs as a place of residence for people who work in the central business district. He argues that a program of re-training and relocation of employable youth in public service programs or communities which could use their services would help reduce one of the major problems besetting the inner city. Finally, Porter proposes that federal aid to local governments should be contingent upon their ability to overcome the need for such assistance in the near future and that a new tax formula could return funds that would ordinarily go to the federal government for much needed reforms and services in urban areas.

Equally optimistic is Edward Bacon, an internationally known planner, who believes that we are witnessing a swing of the pendulum away from suburbia in favor of the central city. Developer James W. Rouse, a major builder of new towns and such shopping malls as Beachwood Place, has predicted that suburbs will be obsolete by the turn of the next century.[66] To further the residential growth of Cleveland’s central city, Stuart E. Wallace, a realtor, recently directed a “Project to Market Cleveland Neighborhoods.” Through this program one hundred and eighty-five realtors volunteered to help by stimulating the buying of homes in Cleveland as a sound investment in the future. Twenty nine out of thirty-five of the city’s neighborhoods passed resolutions endorsing the project. Cleveland’s city hall also created a center to publicize and provide information on the city’s neighborhoods.

Other urban specialists forecast the replacement of the central city’s older core of commercial and manufacturing firms with smaller, more decentralized districts: playhouse-restaurant areas; health complexes; service industries; theatre, museum and educational networks; corporate headquarters; and historic restoration sites. Even manufacturing and commercial enterprises might, once again, flourish in special enterprise zones that result from tax inducements and the availability of cheap land, water, a skilled labor force and transportation facilities.

Neighborhood advocates, however, believe that their needs and priorities should become part of any strategy for revitalizing the city. Enterprise zones should not, for example, come at the expense of other sections of the city or the wage levels of local workers.[67] They contend that plans for developing downtown Cleveland should include such benefits as jobs for local residents or the use of a developer’s repayment of a low interest loan for neighborhood improvements.

One of the major goals of the neighborhood movement is simply to make possible the peaceful living together of people without regard to race, creed or income level.[68] Its supporters believe that preserving and rehabilitating older communities is not nostalgic or utopian but cost effective and a human right in today’s world. Above all, they believe that residents are among those who know what’s best for their neighborhoods and should have the right to influence those decisions which affect their lives.

The neighborhood movement reiterates the social settlement’s concern for a belief environment and the human solidarity of ethnic fraternal organizations. Studying neighborhoods helps us to understand those who advocate their survival and betterment. It also liberates us from many of the misconceptions that have plagued public policy in the past and provides us with a greater appreciation of one of America’s greatest legacies.

Bibliography

Anderson. Nels, The Urban Community. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul, 1960.

Baker, Alan R. H., (ed.), Progress in Historical Geography. London, Wiley future Science, A division of John Wiley, 1972.

Bell, Colin and Howard Newby, Community Studies: All Introduction to the Society of the Local Community. New York, Praeger Publishers, 1971.

Bender, Thomas, Community and Social Change in America. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 1978.

Bernard, Jessie S., The Sociology of Community. Glenview, III.: Scott Foresman, 1973.

Berry, Brian J., “The Counterurbanization Process: Urban America Since 1970.” in Urbanization and Counterurbanization. ed. by Brian J. Berry. London: Sage Publications, 1976.

Bogue, Donald J., Principles of Demography. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1969.

Brown, A. Theodore and Charles Glaab, A History of Urban America. N.Y.: MacMillan Co., 1967.

Chambers, Clarke A., Paul Kellogg and the Survey. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971.

Chapman, Edmund, Cleveland: Village to Metropolis. Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society, 1981 (second edition).

Chermayeff, Serge, et al., Community and Privacy: Toward A New Architecture of Humanism. New York: Anchor Books, 1965.

Chudacoff, Howard. The Evolution of American Urban Society. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall. Inc., 1975.

Clark, Terry. Community Structure and Decision-Making Comparative Analyses. San Francisco, Cal.: Chandler Publishing Co., 1968.

Conzen, Kathleen Neils. “Community Studies, Urban History, and American Local History,” in Michael Kammen (ed.) The Past Before Us: Contemporary Historical Writing in the United States. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1980.

Cunningham, James V., The Resurgent Neighborhood. Notre Dame, Ind.: Fides Publishers, Inc., 1965.

Dent, Borden, ed., Census Data: Geographic Significance and Classroom Utility. Tvalat in Oregon: Geographic and Area Study Publications, 1976.

Domhoff, G. William, The Bohemian Grove and Other Retreats. New York: Harper and Row, 1974.

Downs, Anthony, Neighborhoods and Urban Development. Washington, D.C.: The Brookings Institution, 1981.

Edwards, Richard D., Michael Reich and David M. Gorden, eds., Labor Market Segmentation. Lexington, Mass.: D.C. Heath and Company, 1975.

Exline, Christopher. et al., The City: Patterns and Processes in the Urban Ecosystem. Boulder, Colorado: Westview Press, 1982.

Gans, Herbert. The Urban Villagers. New York: The Free Press, 1962.

Glass, D. U., and Eversley, D. E. C., Population in History: Essays in Historical Demography. London: Edward Arnold, 1965.

Goetze, Rolf, Understanding Neighborhood Change: The Role of Expectations in Urban Revitalization. Cambridge, Mass.: Ballinger Publishing Co., 1979.

Goldfield, David R. and Blaine A. Brownell, Urban America: From Downtown to No Town. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1979.

Green, Howard W., Population Characteristics by Census Tracts, Cleveland, Ohio, 1930. Cleveland: The Plain Dealer Publishing Co., 193 1.

Griffin, Burt W., Cities Within A City. Cleveland: College of Urban Affairs, 1981.

Hartshorn, Truman A., Interpreting the City: An Urban Geography. New York: John Wiley & Sons, 1980.

Hollingsworth, T. H., Historical Demography. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1969.

Hoyt, Homer, The Structure and Growth of Residential Neighborhoods in American Cities. Washington, D.C.: U.S. Government Printing Office, 1939.

Hunter, Albert, Symbolic Communities: The Persistence and Challenge of Chicago’s Local Communities. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Jacobs, Jane, The Death and Life of American Cities. New York: Vintage Books, 1961.

——–., The Economy of Cities. New York: Vintage Books, 1970.

Kazin, Alfred, A Walker in the City. New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1951.

Kornblum, William, Blue Collar Community. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1974.

Lamb, Curt, Political Power in Poor Neighborhoods. Cambridge, Mass.: Schenkman Publishing Co., 1975.

Lieberson, Stanley, Ethnic Patterns in American Cities. New York: Free Press, 1963.

——–., “The Impact of Residential Segregation on Ethnic Assimilation,” Social Forces, 40 (Oct., 1961), pp. 52-57.

——–., “Suburbs and Ethnic Residential Patterns” in American Journal of Sociology, Vol. LXVII, No. 6 (May, 1962), pp. 673-681.

MacIver, Robert M., Society: Its Structure and Changes. New York: Richard R. Smith, 1932.

Minar, David, The Concept of Community. Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co., 1969.

Morris, David, et al., Neighborhood: The New Localism. Boston: Beacon Press, 1975.

Mumford, Lewis, The Culture of Cities. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, Inc., 1938.

O’Brien, David, Neighborhood Organization and Interest Group Process. Princeton, N.J.: Princeton University Press, 1975.

Park, Robert, Human Communities. New York: Free Press, 1915.

Poplin, Dennis, Communities: A Survey of Theories and Methods of Research. New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., 1979.

Redfield, Robert, The Little Community: Viewpoints for the Study of the Human Whole. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1955.

Richardson. Harry W., Regional Economics. Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1979.

Robenson, Ross, History of the American Economy, third edition. New York: Harcourt, Brace, Jovanovich, 1973.

Sanders, Irwin, The Community. New York: The Ronald Press Co., 1975.

Schnok, Leo F. (ed.), The New Urban History: Quantitative Explanations by American Historians. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1975.

Schwartz, Edward, The Neighborhood Agenda. Phil., Pa.: Institute for the Study of Civic Values, 1982.

Schwartz, Edward, editor, Values and Politics: The American Democratic Tradition. Phil., Pa.: The Institute for the Study of Civic Values, 1981.

Stack, Carol, All Our Kin: Strategies for Survival of the Black Family. New York: Harper and Row, 1974.

Stein, Maurice R., The Eclipse of Community. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1964.

Steiner, Stan, La Raza: The Mexican Americans. New York: Harper & Row Publishers, 1967.

Suttles, Gerald, The Social Construction of Communities. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1972.

Thernstron, Stephan, “Reflections on the New Urban History,” in Felix Gilbert and Stephen R. Graubard (eds.), Historical Studies Today. New York: W. W. Norton, 1972.

Timms, D., The Urban Mosaic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1971.

Ward, David, Cities and Immigrants. New York: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Ward, David (ed.), Geographic Perspectives on America’s Past: Recordings on the Historical Geography of the United States. New York: Oxford University Press, 1979.

Warren, Roland, The Community in America. Chicago: Rand McNally College Publishing Co., 1978.

——–., Perspectives on the American Community, Chicago: Rand McNally, 1973.

——–., Studying Your Community. New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1955.

Weber, Adna Ferrin, The Growth of Cities in the Nineteenth Century: A Study in Statistics. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1967 [c. 1899].

Whyte, William F., Street Corner Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1967.

Wilson, Robert A., et al., Urban Sociology. New Jersey: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1978.

Wrobel, Paul, Our Way: Family, Parish, and Neighborhood in a Polish-American Community. Notre Dame, Ind.: University of Notre Dame Press, 1979.

Zelinsky, Wilbur, A Prologue to Population Geography. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, Inc., 1966.

- Dennis E. Poplin. Communities: A Survey of Theories and Methods of Research. (New York: MacMillan Publishing Co., Inc., 1979), p. 8. See also David W. Minar and Scott Greir (eds.) The Concept of Community. (Chicago: Aldine Publishing Co., 1969); Roland L. Warren, The Community in America. (Chicago: Rand McNally and Co., 1978) and Colin Bell and Howard Kewby, Community Studies: An Introduction to the Sociology of the Local Community. (New York: Praeger Publishers, 1972). ↵

- Robert M. MacIver. Society: Its Structure and Changes. (New York: Richard R. Smith. 1932), pp. 9- 10. ↵

- Warren, pp. 9- 11. ↵

- Gerald Suttles, The Social Construction of Communities. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press. 1972), p. 47. ↵

- Louis Wirth, '"Urbanism As A Way of Life" in The American Journal of Sociology, 44 (July, 1938). pp. 1- 24 and Robert Park, "The City: Suggestions for the Investigation of Human Behavior in the City" in Human Communities. (New York: Free Press, 1915). ↵

- Herbert Gans, People and Plans. (New York: Basic Books, 1968). ↵

- Lewis Mumford, The Culture of Cities. (New York: Harcourt, Brace. Jovanovich, Inc., 1938). ↵

- Constantinos A. Doxiades, "The Ancient Greek City and the City of the Present," Ekistics 18 (November. 1964). p. 360. ↵

- Suzanne Keller, The Urban Neighborhood: A Sociological Perspective. (New York: Random House, 1968), pp. 156- 157. ↵

- Poplin, pp, 300-310. ↵

- Clarke A. Chambers, Paul Kellogg and the Survey. (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1971), p. 38. ↵

- See Edward M. Miggins; "Businessmen, Pedagogues and Progressive Reform: The Cleveland Foundation's 1915 School Survey" (Ph.D Dissertation, Case Western Reserve University, 1975). ↵

- Charles E. Hendry and Margaret T, Svendsen, Between Spires and Stacks. (Cleveland: The Welfare Federation, 1936). PP, 24-25. ↵

- Robert B. Navan, An Analysis of A Slum Area in Cleveland. (Cleveland: Regional Association of Cleveland, 1939). ↵

- "Housing Price Appreciation and Race in Cuyahoga County," (Cleveland: The Cuyahoga Plan of Ohio, Inc., June, 1982). pp. 1 and 5. The author would like to thank Richard Oberman of the Cuyahoga Plan for sharing the reports of this agency. ↵

- Herbert Gans, The Urban Villagers. (New York: The Free Press, 1962). ↵

- Carol Stack, All Our Kin: Strategies for the Survival of the Black Family. (New York: Harper and Row, 1974), p. 146. ↵

- Eugene Uycki, "Ethnic and Race Segregation in Cleveland, 1910-1970," Ethnicity, 7 (Dec., 1980). pp. 390- 403. ↵

- Daniel Weinberg, "Ethnic Identity in Industrial Cleveland: The Hungarians. 1900-1920," Ohio History. Vol. 86 (Summer, 1977), p. 184. ↵

- See David Morris, et al., Neighborhood Power: The New Localism. (Boston: Beacon Press, 1975). ↵

- Timothy Barrett, The People Are the City: Three Cleveland Neighborhoods, 1796- 1980. (Cleveland; The Cuyahoga County Archives, 1980), p. 31. ↵

- Howard Whipple Green. Population Characteristics by Census Tracts. (Cleveland, Ohio, 1930). (Cleveland: The Plain Dealer Publishing Co., 1930), pp. 11- 13. See also Kenneth Kusmer, A Ghetto Takes Shape. (Urbana, Ill.: University of Illinois Press, 1978), p. 147. ↵

- See "Black Homeownership in the Cleveland Area: Patterns of Residence in 1970 and 1980." (Cleveland: The Cuyahoga Plan, Oct., 1982) and "Black Homeownership in Greater Cleveland: Whittling Away at Segregated Housing Markets, 1970-1980." The Cuyahoga Plan's Open Housing Report. (Jan.-Feb., 1983) and the Plain Dealer, Ap. 27, 1983. ↵

- See Stanley Lieberson, Ethnic Patterns in American Cities. (New York: Free Press, 1963), and Nathan Kantrowitz. "Ethnic Segregation: Social Reality and Academic Myth" in Ethnic Segregation in Cities. Cori Peach and Susan Smith, ed. (Athens, Ga.: The University of Georgia Press, 1981), pp. 43-57. ↵

- Albert Hunter, Symbolic Communities: The Persistence and Change of Chicago's Local Communities. (Chicago: The University of Chicago Press, 1974). ↵

- Kusmer. p. 171. ↵

- Keller, p. 89. ↵

- For a more extensive list, see Roland Warren, Studying Your Community. (New York: Russell Sage Foundation, 1955). ↵

- "Governmental Facts" (Cleveland: Governmental Research Institute, April 22. 1981). ↵

- The Inconspicuous Governments: An Inventory of Special Governmental Agencies in Cuyahoga County. (Cleveland: Governmental Research Institute, 1976), pp. 4-6. ↵

- Burt W. Griffin, Cities Within A City. (Cleveland: Cleveland State University's College of Urban Affairs, 1981). ↵

- Minar, p. 15. ↵

- Morris, p. 73. ↵

- Christen T. Jonassen, "Cultural Variables in the Ecology of an Ethnic Group." in Neighborhood and Ghetto: The Local Area in Large-Scale Society. Scott Greer, et al., editor. (N.Y.: Basic Books, Inc., 1974), p. 187. ↵

- For an excellent analysis of the work of Robert Park and Louis Wirth see the following, Maurice R. Stein, The Eclipse of Community. (New York: Harper and Row, Publishers, 1964) and Michael P. Smith, The City and Social Theory, (N.Y.: St. Martin's Press, 1979). ↵

- Amos Hawley, "Human Ecology: A Theory of Community Structure," in Community Studies: An Introduction to the Sociology of the Human Community. Colin Bell, ed., et al. (New York: Praeger Publishers. 1971), pp. 35. ↵

- Robert A. Wilson, Urban Sociology. (New Jersey: Prentice Hall, Inc., 1978), p. 147. ↵

- Community. (New York: Time-Life, 1976). p. 47. ↵

- Suttles, p. 6. ↵

- See Kevin Lynch, "The Image of the City" in Urban Studies: An Introductory Reader. (New York: The Free Press, 1977), Louis K. Lowenstein, ed., pp. 360- 361. ↵

- The author is indebted to Prof. Darwin Stapleton of the American Studies Dept. of Case Western Reserve University for this information. ↵

- Wilson, p. 149. ↵

- Hunter, p. 71. ↵

- See Wellington Fordyce, "Immigrant Colonies in Cleveland Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, XLV, (1936), pp. 320-340 and "Attempts to Preserve Nationality Cultures in Cleveland," Ohio State Archaeological and Historical Quarterly, XLIX (1940), pp. 128-149. See also The Peoples of Cleveland, compiled by Workers of the Writers Program of the Work Projects Administration, (Cleveland: 1942) and the Ethnic Heritage Series of Cleveland State University. ↵

- See Fordyce, "Attempts . . . " p. 129 und Barbara Gartland. "The Decline of Cleveland's Roman Catholic Nationality Parishes," (Unpublished M.A., Cleveland State University, 1973) ↵

- See Lloyd P. Gartner, History of the Jews of Cleveland. (The Western Reserve Historical Society and The Jewish Theological Seminary of America, 1978), pp. 101-135. ↵

- See Stanley Lieberson, Ethnic Patterns in American Cities. (New York: Free Press, 1963). ↵

- See Russell Davis, Black Americans in Cleveland. (Cleveland: Associated Publishers, 1972) and Kusmer, p. 216 and pp. 149-151. ↵

- "The Hiram House and Its Work," in Cleveland Women, Aug. 25, 1917. See also John Grabowski, "From Progressive to Patrician: George Bellamy and Hiram House Social Settlement, 1896-1914," Ohio History, Vol. 87, (Winter, 1978), pp. 37-50. ↵

- Margaret Svendsen, et al., Between Spires and Stacks. (Cleveland: The Welfare Federation or Cleveland, 1936), pp. 115- 121. ↵

- "Greater Cleveland Neighborhood Centers Association, 85th Anniversary Celebration and United Neighborhood Centers of America, Central Lakes Regional Conference: Conference Proceedings," (Cleveland, 1981), p. 14. ↵

- Ibid., p. 76. ↵

- Interview with Robert Bond, Cleveland Heritage Program. July 21, 1983. Bond is the current director of the Association. ↵

- "Plan for Action for Tomorrow's Housing in Greater Cleveland." (Cleveland, 1968), p. 18. ↵

- Edric A. Weld, "The Demographic Setting for the Eighties for the Cleveland Region," (Cleveland: Cleveland State University, 1980), p. 23. ↵

- Norman Krumholz, "A Retrospective View of Equity Planning, " American Planning Association Journal, (Spring, 1982), p. 164. The author served as Cleveland's Planning Director from 1969 to 1979 and is currently the Director of the Center for Neighborhood Development in the College of Urban Affairs, Cleveland Suite University. ↵

- See "Housing Abandonment in Cleveland," (Cleveland: City Planning Commission, 1972) and "Housing for Low-and-Moderate-Income Families," (Cleveland: City Planning Commission, 1972). ↵

- Karl Hess, Dear America. (New York: William Morrow & Co., Inc., 1975), p. 239. ↵

- See Edward Schwartz, "Values and Politics: The American Democratic Tradition," (Philadelphia: The Institute for the Study of Civic Values, 1981). Schwartz is the director of the Institute. ↵

- Roslyn Block, "Resources for Cleveland Neighborhood Groups," (N.P., 1980). The author is the director of the Cleveland Housing Network, a coalition of six neighborhood based non-profit housing corporations. See The Plain Dealer, Oct. 1, 1983. ↵