Part II. How to Study Your Neighborhood

Maps and City Directories

Jeanne Kish

Maps, directories and atlases are often overlooked as potential sources of information about a neighborhood. But for the individual who is willing to spend some time with them, they can yield some fascinating facts.

Usually available through libraries or archives, maps and atlases furnish information about the original look of a neighborhood, the physical changes which have taken place over a period of time, and the types of businesses and industries, as well as residential dwellings, which have been located there at different times. Directories provide supplemental information about these topics such as the names of residents, house numbers and the types of businesses found in the neighborhood.

Maps can be found in three places: 1) atlases and city directories; 2) surveys published by insurance companies to determine the insured value of a residence or business; and 3) general historical surveys of a city or section of a city.

Maps from atlases and city directories provide the researcher with an overview of the city’s layout. Comparisons can be made between these maps to show changes which have taken place in the layout of city streets, especially those vacated or altered by new construction.

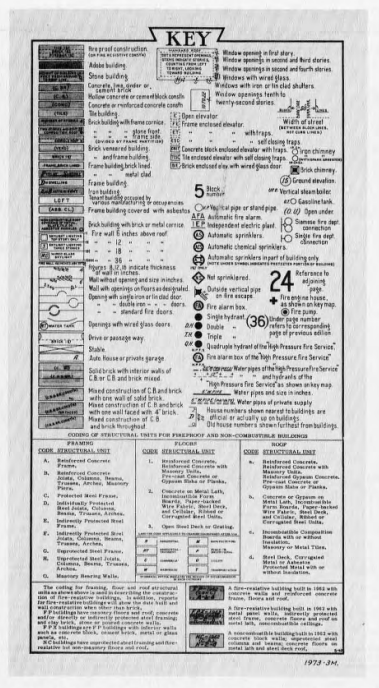

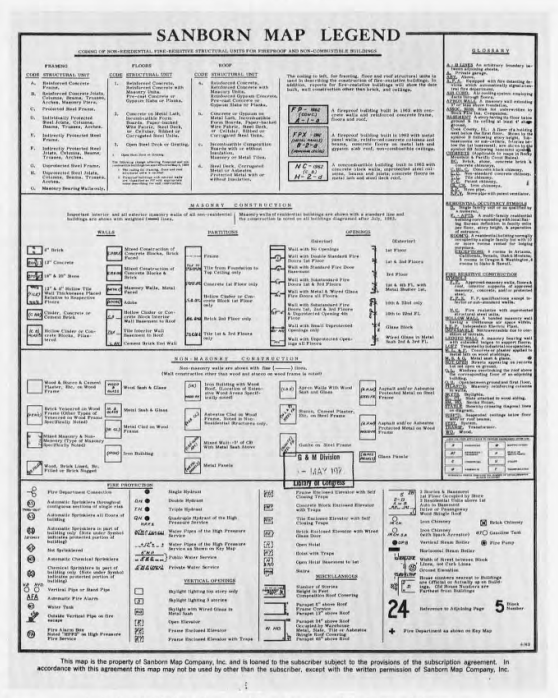

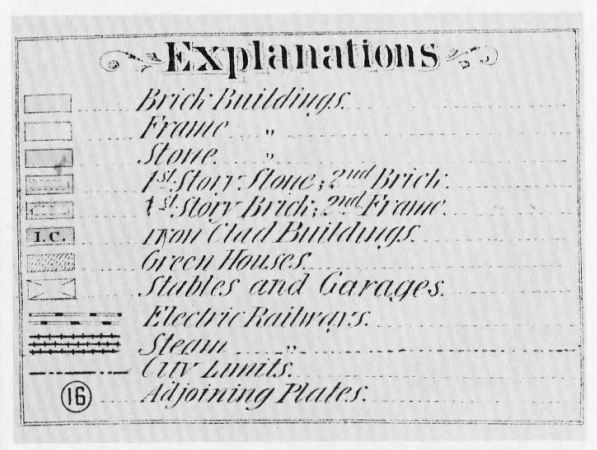

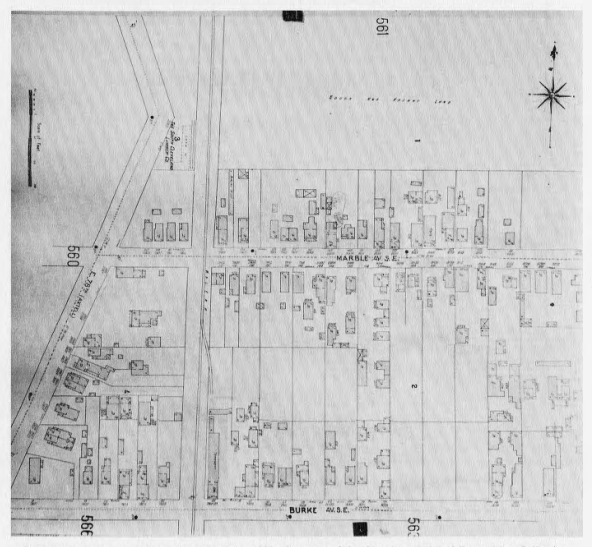

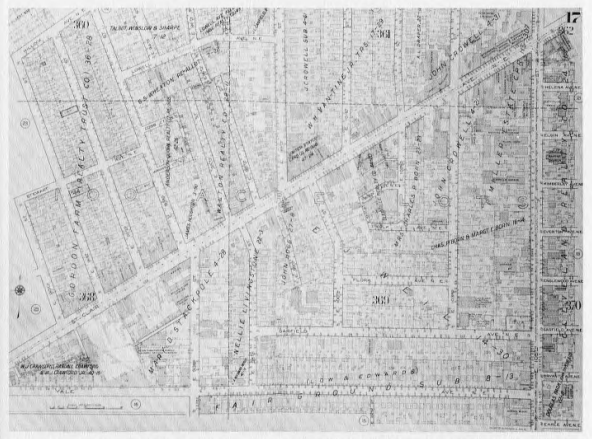

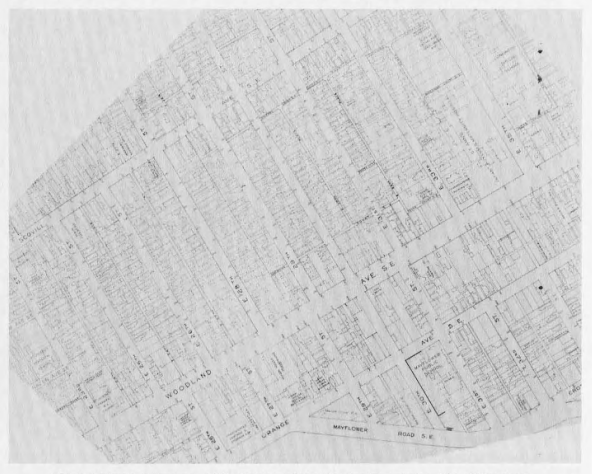

Maps published by insurance companies, such as the Sanborn and/or Hopkins series, can provide a vivid portrait of a neighborhood, and a researcher who knows how to read them can glean a tremendous amount of information from them. Insurance maps are prepared for the purpose of simplifying the process of determining insurance rates for a metropolitan area. They can tell a researcher such things about a given neighborhood as: 1) how land areas are divided into lots; 2) what types of buildings are located on a lot (their construction material, the number and layout of rooms and the number of floors, as well as what additional auxiliary buildings are found on the same lot; 3) what institutions, businesses or industries are located in the neighborhood. A survey of several maps made of the same area over successive periods of time can show the amount of change that has taken place. An explanation key to both the Hopkins and the Sanborn map series is published by the Library of Congress. The surveyor should remember that neither map series is published annually, but rather at irregular intervals, to allow the recording of the maximum number of changes.

A type of map which also indicates lot sub-division is the plat map. These are usually compiled for the purpose of determining property ownership in order to assess real estate taxes. They are available through the county offices and will be discussed in the section dealing with county and city records.

While city directories are perhaps more important to the individual putting together a family history, they are also useful to the researcher attempting to piece together a picture of a neighborhood. City directories provide information about street references, an alphabetical listing of residents, a listing of businesses by category in alphabetical order, and listings of organizations and churches located in the area. Some directories include maps of railway lines and streetcar routes, and even sample advertisements for businesses found in an area.

Researchers should remember that the information in the directories (particularly those compiled before 1920) was gathered by people who were not necessarily familiar with the neighborhood or the main ethnic group residing there so, in attempting to find a particular name, the researcher should look under several possible spellings in addition to the correct one. Names were often spelled phonetically, especially in the case of new groups of immigrants who had not yet mastered the English language. (The name Copeland might also appear, for example, as Copland, or even Kaplan, among other possible variations.). Similarly, in the case of different types of employment, terms with which the compilers were not familiar may be listed after a person’s name in the residential listings.

Most neighborhoods have supported many small businesses through the years. By tracking a particular address, a person can determine who resided or maintained a certain business at that site. For example, between 1895 and 1905 three different businesses occupied a building at 2846 Central Avenue (formerly 564 Garden). In 1895, F. A. Stewart ran a saloon at that address. By 1905, two businesses were housed in the same building, a grocery store owned by Maria B. Fields and a meat market operated by Louis Cohen.

It is also possible to recreate the commercial and residential composition of any given street in a particular year. In 1910, Fleet Avenue between East 65th Street (then called Tod Street) and East 71st Street (Marcelline Street) was the location of a wide variety of businesses as well as residential homes. The street would have looked something like this:

| 6505 Fleet | Stranislaus Marlewski | dry goods |

| 6514 Fleet | Michael Gazka | confectioner |

| 6515 Fleet | Andrew Klebowski | saloon |

| 6518 Fleet | Thomas Konicki | tailor |

| 6519 Fleet | Lorenc Alexandrowicz | retail clothing |

| 6522 Fleet | Peter Sawicki | boots and shoes |

| 6616 Fleet | Leocadie Dziewczynski | dressmaker |

| 6700 Fleet | Leon H. Karasiwiecz | grocer |

| 6708 Fleet | Joseph Waszkowski | saloon |

| 6716 Fleet | Appolonia Torkowski | dressmaker |

| 6815 Fleet | Paul Schultz | carpenter |

Interspersed with private residences, this street in the Broadway-Fleet area presented, as did comparable streets in other neighborhoods in the city, a microcosm of the city as a whole. The alphabetical listing by type of business will provide a wealth of information in the reconstruction of a neighborhood’s economic life.

In the course of his work the researcher might want to raise some of the following questions about the local business community he has uncovered in the city directory, such as:

- What conditions or geographic factors in a given neighborhood would have caused a business/industry to locate there?

- Whom did these businesses/industries employ?

- What types of businesses/industries were most numerous in the neighborhood? Why? During which time periods?

- How and why did the types of businesses/industries change over a given period of years?

- How did the businesses/industries change as technology changed?

- What occupations disappeared over the years as a result of changes in technology (automation, etc.)?

- What businesses/industries left a particular area, while remaining in another? Why did this happen?

- Why did some businesses/industries serve only a given neighborhood or specific group (ethnic or social class) within a neighborhood?

- Why did some businesses/industries turn to specialization and begin to serve the entire city rather than a specific neighborhood? What types of businesses/industries underwent this kind of change?

- Most directories carry advertisements for businesses/industries, but an observant researcher will note that not all appear there. Why did some businesses/industries have little or no need to advertise themselves to the residents of a neighborhood?

Atlases, maps and city directories, in short, can help the researcher willing to look off the beaten path for pieces of the puzzle and put together a detailed picture of a neighborhood.

Bibliography

Clay, Grady, Close-Up: How to Read the American City. New York: Praeger, 1972.

Hart, John Fraser, et al., Cultural Geography on Topographic Maps. New York: Wiley, 1975.

——–., The Look of the Land. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1975.

Knights, Peter R., The Plain People of Boston, 1830-1860. N.Y.: Oxford University Press, 1971.

Gear, Clara E. L., United States Atlases: A List of National, State, County, City and Regional Atlases in the Library of Congress. 2 vols. Washington, D.C.: Library of Congress, 1967.

Reps, John W., The Making of Urban America: A History of City Planning in the United States. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1965.

Schlereth, Thomas J., “Part Cityscapes: Uses of Cartography in Urban History,” in Artifacts and the American Past. Nashville, Tenn.: American Association of State and Local History, 1980, pp. 66-86.

Thrower, J. W., Maps and Man: An Examination of Cartography in Relation to Culture and Civilization. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall, 1972.