Part II. How to Study Your Neighborhood

Census Materials

Ronald Weiner

Even when no other sources are available, the neighborhood historian need not despair. A wealth of information about cities and their neighborhoods can be found in what might have seemed a most unlikely place: the census. This section will explain the nature of census materials and explore their uses.

Every ten years since 1790, the United States Bureau of the Census has been counting Americans and publishing reports on the country’s population, its size, rates of growth, age and sex composition—as well as recording data on such matters as the marital status and number of children, occupations and place of origin of U.S. citizens. There are separate reports for states, counties and cities. While the full range of questions asked by the census lakers varies from decade to decade, the above information is available in most censuses. And it can provide the student of neighborhood history with intimate details of neighborhood life.

Census information (or data) comes in two forms: printed reports and the manuscript census itself. The reports, which have been issued for every census taken since 1790, are generally available to researchers in most locales. Though the reports published in the nineteenth century subdivide urban populations into city wards, these can be made to correspond to neighborhoods. Beginning with the 1910 census, the Census Bureau began to use the census tract as its basic urban unit. Consisting of between 3,000 and 5,000 persons living in close geographical proximity, the census tract is more useful than the wards because the former, being smaller, can be aggregated to correspond precisely to neighborhood boundaries.

For the study of nineteenth century cities and neighborhoods, however, the original manuscript census is probably more valuable. The manuscript census consists of the actual folio pages on which the census takers wrote their entries in long hand. The typical page records the individual’s name, address, age, sex, marital status, country (or place) of origin, occupation and, in some years, whether he owned or rented his home. The manuscript census pages are organized by street address, city block and ward, a very valuable format for the neighborhood historian who can itemize the information on a separate data sheet.

The best guide to how the census information was collected in a given year, what questions were asked, and what reports were published is the Bureau of the Census Catalogue of Publications, published by the Department of Commerce.

Both printed and manuscript census materials are available in the Cleveland area. The Cleveland Public Library owns a complete set of the printed census reports dating all the way back to 1790. The 1980 printed census reports are now being issued and are available at the CPL on microfiche. The Cleveland State University Library also has the printed census reports as does Freiberger Library of Case Western Reserve University, though certain items are missing and others are showing the ravages of age and use.

Clevelanders are very fortunate in that original manuscript census materials are available locally on microfilm. The Western Reserve Historical Society is one of only three libraries in the United States to own the complete U.S. Census manuscript census for each decade from 1790 to 1900. The highly useful 1910 manuscript census will soon also be available to local scholars. The remaining years of twentieth century manuscript censuses are not yet open to users. The library of the Eastern Campus of Cuyahoga Community College has the manuscript census for Cuyahoga County from 1850 to 1900—with exception of the 1890 manuscript census, which was, unfortunately, destroyed by fire and is not available anywhere.

Anyone interested in the history of Cleveland’s neighborhoods should consult, in addition to the census materials already mentioned, the printed reports of the Real Property Inventory of Cleveland. These record a great variety of post-1910 demographic and housing data by census tract and even city block. Although the Real Property Inventory itself has ceased to exist as a government agency, its reports can be found in the Cleveland Public Library, and its files and maps are housed at Cleveland State University’s College of Urban Affairs.

Demographic Measurements Derived from Census Data

People who analyze population data are called demographers—after the Greek word demos meaning “people” and graphein meaning “to write or represent pictorially,” as with a graph. But sophisticated knowledge of the field is not necessary in order to gain valuable insights about a population from census data. There are a variety of uncomplicated demographic measurements which can provide the student with a wealth of information about the social and economic characteristics of a neighborhood. Any demographic measurement, however, is more valuable if it can be compared with those of other neighborhoods or the city at large. Chicago School sociologists and those who conducted the Pittsburgh Survey relied heavily on census data and demographic measurements in their work.

Population Size and Growth

The first step in neighborhood demography is to determine the number of people who live in the area. Using the manuscript, the student simply makes a tally of all the residents who live in the neighborhood. A card on each resident recording all the information that was gathered about that person is the most efficient way to proceed since eventually all of the census information will be needed. The printed census is easier to work with than the manuscript pages, however, because it is organized either by wards or by census tracts, which can be aggregated to fit the boundaries of the neighborhoods one is interested in.

Population growth (or decline) is one important element in neighborhood analysis. Radical shifts in population size over a period of time suggest that significant events may be occurring in the neighborhood. For example, the population in Cleveland’s Central West Neighborhood (see Table 1) has been declining in every decade since 1910. This trend may be traceable to many neighborhood dynamics; it suggests, at the very least, that people were leaving the inner city at a much earlier date than experts have traditionally thought.

The technique for measuring population change over time is to divide the total figure for the later census by that for the earlier census, multiply the result by 100, and subtract 100 from that figure. For example, Cleveland Central West Neighborhood had a 1960 population of 33,790 and a 1970 population of 16,882. To get the rate of change, the 1970 population of 16,882 is divided by the 1960 population of 33,790. The resulting figure of .4996 is then multiplied by 100 and 100 subtracted from the answer (49.96), giving a minus 50.04 percent—the rate of decline (expressed as a percent) in the neighborhood’s population between 1960 and 1970.

Sex and Age Structure of the Neighborhood Population

Once a neighborhood’s size and rate of growth have been established, the population should be divided into males and females. A sensitive demographic measurement called the sex ratio can be calculated very simply by dividing the number of females by the number of males and multiplying the resulting figure by 100.

The sex ratio, which measures the number of males per 100 women, has been used by scholars as an indicator of urbanization. Rural populations typically have more males than females, and urban populations typically have more females than males. Within a city the sex ratio is equally important. A neighborhood with a high male-to-female ratio is usually where one finds recent migrants to the city, people who tend to be males. In 1970, the Downtown neighborhood of Cleveland, a point of entry for migrants (as well as the location of the county prison population), had a sex ratio of 257 (males to 100 females) compared with 90 for the city at large and 80 for the Central West area. A sex ratio of 80 in a neighborhood like Central West, which we have established is experiencing a rapid population decline, suggests that more males than females are leaving.

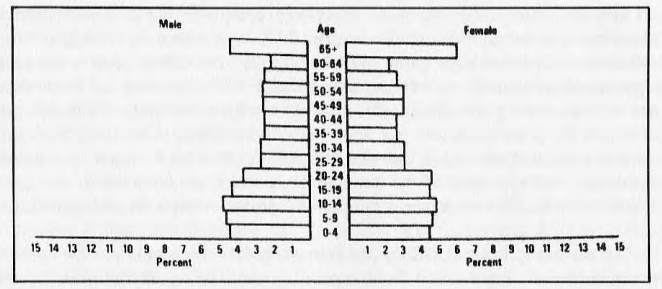

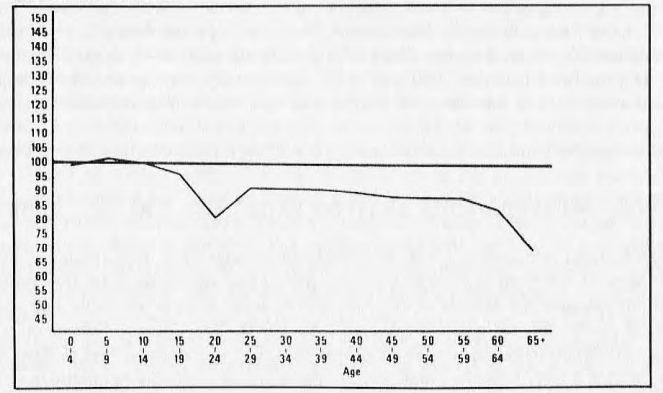

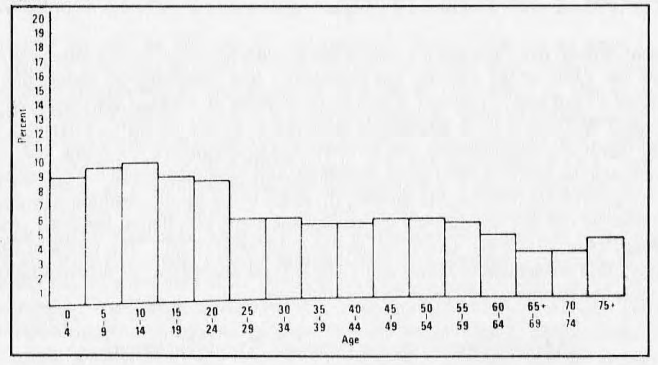

Knowledge of the age structure of the population allows for a still more intimate look at the neighborhood. Age and sex data are typically compiled in graph form: the age histogram and the age-sex pyramid (see Population Pyramid Figure). The age histogram is drawn by subdividing the entire population into five-year age intervals (0-4, 5-9, 65 plus, etc.) called cohorts. The population in each cohort is then divided by the total population of the neighborhood and the resulting figure multiplied by 100 to get the percentage of the population which falls into that age group. In the Central West neighborhood in 1970, for example, there were 1,665 people from newborn to four years of age. So 1,665 is divided by the total population of the neighborhood, 16,882, and the resulting figure multiplied by 100, giving a percentage of 9.8. This calculation is then made for each cohort and the emerging pattern expressed in graph form as the age histogram (see Age Histogram Figure).

Table 1

| Central West Social Planning Area is located entirely in the City of Cleveland and is bounded by Eagle Ave., Erie Street Cemetery, Euclid Ave., East 55th St., the railroad tracks, East 34th St., Dille Ave. and the Cuyahoga River. | |||

1. Demographic Profile |

|||

| Central West is composed of the following census tracts: 1079, 1087, 1088, 1089, 1091, 1092, 1093, 1096, 1097, 1098, 1099, 1101, 1102, 1103. |

|||

| Total Population 1970 | 16,882 | Composition | – |

| Change from 1960-1970 | -16,908 | Black Population | 82.2 |

| % Change | -50.0 | Persons of Native Stock | 94.6 |

| Population Estimate 1976 | 16,209 | Persons of Foreign Stock | 4.8 |

| % Change from 1970-76 | -4.0 | White Population | 18.8 |

| Age | Income | ||

| 0-4 | 1,655 | Median Family Income | $3,935.00 |

| 5-9 | 1,841 | Income Score | 23 |

| 10-14 | 1,956 | ||

| 15-19 | 1,776 | Labor Force Characteristics | |

| 20-24 | 1,306 | General Activity Rate | 660 |

| 25-34 | 1,502 | Crude Activity Rate | 273 |

| 35-54 | 2,725 | Women as % of Labor Force | 46.6 |

| 55-65 | 1,540 | Manual Laborers as % of Labor Force | 73.7 |

| 65+ | 2,581 | Occupational Score | 28 |

| Age Index Value | 68 | ||

| Housing | |||

| Sex | Number of Housing Units (1970) | 5,556 | |

| Sex Ratio | 80 | % Change (1960-1970) | -31.5 |

| Fertility Ratio | 538 | % Owner Occupied | 3.6 |

| Births | % Overcrowded | 10.9 | |

| 1968 | 393 | No. of Housing Units 1976 | 6,268 |

| 1969 | 369 | % Change from 1970 | -11.7 |

| 1970 | 426 | Population Density | 10.8 |

| 1971 | 358 | ||

| 1972 | 356 | Education | |

| 1973 | 271 | % Completing 1-7 yrs. of School | 29.4 |

| 1974 | 274 | % Completing 12 yrs. of School | 19.9 |

| – | % Completing 4 yrs. of College | 2.2 | |

| Dependency | Median School Years Completed | 9.9 | |

| Dependency Ratio | 943 | Educational Attainment Score | 59.5 |

| Youth Independency | 660 | ||

| Old Age Independency | 283 | Educational Index Score | 43.8 |

Table 2

Courtesy of Ronald Weiner’s “Educational Panning Catalog,” Cuyahoga Community College, 1976.

The age histogram is a measure of age concentrations found in a neighborhood. In the Central West area, for example, 9.8 percent of its population was in the 0-4 cohort compared with 7.4 percent for the suburbs, suggesting a higher birth rate in the inner city neighborhood. Shaker Heights, to use another suburban example, yields an age histogram showing few children 0-4 and correspondingly few adults 20-30 but large concentrations of school age children 5-18. One might conclude that the suburb has an attractive school system but is an expensive place to live for people in their twenties just entering the labor force, who do not have children of school age.

The age-sex pyramid breaks the population into age and sex cohorts. All females 0-4, 5-9, etc. are counted, then the same done with their male counterparts. Each age-sex cohort is divided by the total population to determine what percentage that subgroup (e.g., males 5-9) is of the neighborhood’s overall population. An age-sex pyramid is then drawn on graph paper showing male cohorts on the left side and female cohorts on the right side of the pyramid (see Population Pyramid Figure).

The age-sex pyramid, like the age histogram, facilitates demographic interpretation and neighborhood analysis. The shape of the drawn pyramid reveals much about the nature of growth being experienced by the neighborhood. A Christmas tree-shaped pyramid (one in which as much as 50 percent of the population is under age fifteen) is characteristic of a very rapidly growing place, while a pyramid shaped like a ladder indicates a population that has experienced stable growth rates for many years. The Central West area’s pyramid displays yet another pattern, for it shows abnormal indentations for males between 25 and 35 and females 25 to 45, bringing us a step closer to discovering who left the neighborhood between 1960 and 1970. Additionally, we can see that nearly 7.0 percent of the neighborhood’s population consists of females over 65 years of age, which may help to explain the sex ratio of 80 noted earlier.

The age structure of a neighborhood, then, can be a very revealing indicator of population change dynamics.

Other Measurements Derived from Age and Sex Data

Age and sex data can be used to calculate a host of significant demographic measurements, including the fertility ratio, a broad measurement of the birth rate. It is normally used when information on live births in an area is not available. The calculation is simple: the number of children of both sexes from newborn to four years of age is divided by the number of women 20-44 and the result is multiplied by 1,000. The Chicago School of Sociology found that the fertility ratio was an important indicator of urbanism because urban populations tend to have lower fertility ratios than rural populations. Within a city, however, high fertility ratios usually indicate populations recently arrived in the city, or those of lower socioeconomic status, or those with cultural values emphasizing large families. The fertility ratio for Central West in 1970 was 538, a substantially higher figure than the 393 ratio recorded for Cuyahoga County as a whole.

A second measurement derived from age and sex data is the dependency ratio, which measures the number of youth and old age dependents per 1,000 of the working age population. It is calculated by adding the number of children 0-20 to males and females 65 and over, dividing the sum by the number of working age people 20-65 and multiplying the result by 1,000. Central West has a 1970 dependency ratio of 943 compared with a Cuyahoga County dependency ratio of 486, suggesting that it is a neighborhood that probably needs schools for the young and services for the aged. The dependency ratio can also be recast to distinguish between youth dependency and old age dependency. The figure for youth dependency is derived by dividing the number of youth 0-20 by the working age population 20-65 and multiplying by 1,000; that for old age dependency by making the same calculation for those over 65. Central West shows a youth dependency ratio of 660 and an old age dependency ratio of 283. The ratios of Cuyahoga County are 324 and 162 respectively. This refinement confirms that Central West dependency is oriented more toward youth than old age, though both rates are substantially higher than county averages.

Measurements of Social Stratification

The twentieth century census reports provide valuable information on race, ethnicity, occupation, income, educational attainments and housing. This data can be used to compile a social and economic profile of the neighborhood which reveals much about its social class structure as compared with other neighborhoods or to the city as a whole.

Race and ethnicity are important characteristics to identify in a neighborhood population because racial and ethnic groups are frequently segregated in certain sections of a city. Demographers have sophisticated tools for measuring segregation, but even without these tools the neighborhood historian can learn much about segregation simply by comparing the percentage of a given group found in the neighborhood under study with the percentage of that same group found in the city at large. In Central West 82.2 percent of the 1970 population was black, yet 38.3 percent of Cleveland’s population was black during the same period. Expressed another way, Central West housed 2.2 percent of Cleveland’s population but 4.8 percent of Cleveland’s black population. These simple percentage yardsticks indicate that Central West was a highly segregated neighborhood in 1970. The same measurements can be applied to any of the ethnic groups found in Cleveland’s population.

Labor force characteristics are also important indicators of socioeconomic status, and several techniques can be used to measure them. One of these is the general activity rate, which measures the ratio of those over 15 years old to the total population of the neighborhood. Simply stated, the population under 15 is divided by the neighborhood population and the resulting figure multiplied by 1,000. Central West’s general activity ratio is 660 compared with 628 for the city of Cleveland, a favorable comparison suggesting that Central West has a large labor force. But the general activity rate can be deceptive, as it is in this comparison, since it does not indicate what percentage of the neighborhood’s working age population is in fact working. The crude activity rate is more useful because it measures the number of people actually employed divided by the total population of the neighborhood. The crude activity rate of the Central West area is 273 compared to the city of Cleveland’s 402. Although Central West has a large labor force potential, few actually have jobs. Unemployment is far more common in the Central West neighborhood than it is in the city of Cleveland.

Measures of social stratification can also be calculated from occupational data. The census bureau reports nine occupational categories. An occupational histogram may be drawn for the neighborhood showing the percentages of the labor force in each occupational category, which can then be compared with similar graphs for other neighborhoods or the city at large. A related measurement of social stratification is the occupation index. This is based on the percentage of the neighborhood’s labor force employed in the manual labor category. High percentages in manual labor are indicators of low socioeconomic status. The percentage of the labor force in the manual labor category should be calculated for each neighborhood in the city. The neighborhood with the highest percentage of manual labor is then divided into the number 100, producing a constant. Each neighborhood percentage is then multiplied by the constant to determine its percentage of 100. For example, the Goodrich neighborhood of Cleveland in 1970 had 75 percent of its labor force in the manual labor category, the highest in the city. So 100 is divided by 75, producing 1.333 as the constant. Each neighborhood’s manual labor percentages are then multiplied by 1.333, which generates its occupation index score. West Central, for example, had 73.7 percent of its labor force employed in manual labor, when multiplied by 1.333, produces an occupational index score of 98.2 for West Central. Shaker Heights’ 5.7 percent produces an index value of 7.6, suggesting the range of social status differences between Central West and Shaker Heights.

Educational attainments are also an indicator of socioeconomic status. The census since 1930 reports by census tract the number of years of schooling attained by each resident. From this data an educational attainment index can be computed for the entire neighborhood. The arithmetic involved in calculating an educational attainment index is the same as that used for the occupation index. The median number of years of education for each neighborhood is calculated, the highest figure is then divided into 100 to get a constant, and then each of the median values is multiplied by the constant. Shaker Heights has the highest median years of school completed at 13.5. This figure is then divided into 100, producing a constant of 7.407. Central West’s median of 9.9 is then multiplied by 7.407, which yields an educational attainment score for Central West of 73.3. The lowest 1970 educational attainment score in Cleveland was 69.6, showing that Central West was closer to the low end of the spectrum than to the high end.

Finally, the recent censuses also report median incomes, the most important indicator of relative socioeconomic status. An income index can be calculated using the same techniques used to compute the occupation index and the educational attainment index. The highest median income, once again, is divided into 100, yielding a constant value, which is in turn multiplied against the median incomes of each neighborhood. Shaker Heights, which is again the highest, equals 100, giving Central West a score of 23 on the income index, one of the lowest in the county.

Cleveland is an excellent place to study neighborhoods. The city’s libraries have the basic sources needed in the form of printed census and manuscript census materials. These materials easily lend themselves to the kind of demographic analysis explained in this section.

It is probably advisable for the neighborhood historian, student or professional, to begin his or her study by considering a neighborhood demographic profile for the period of time he or she is studying. This enables the historian to measure facts or figures derived from other sources against some solid conclusions concerning the demographic fabric of the neighborhood. Demographic analysis enables the historian to see the forest, while more traditional historical sources and techniques of analysis enable him or her to see the complex variety of trees which make up the forest.

Data Sheet |

|||

| Indiv: # | Census Year: | ||

| – | Ward: | Pct.: | Census Page: |

| Name: | Age: | Sex: | Color: |

| Occupation: | |||

| Household Head: Son: Daughter: Other: | |||

| Real Estate Value: | Personal Estate Value: | ||

| Birthplace: | Birthplace Father: | ||

| Res: | Birthplace Mother: | ||

| Married: Single: Widowed: Divorced: U.S. Citizen: | |||

| Months Unemployed: | Disabled: | ||

| If Married: | |||

| Spouse’s Name: | Age: Occupation: | ||

| Birthplace: | Birthplace Father: | ||

| Res: | Birthplace Mother: | ||

| Children (total number): | or Siblings (total number): | ||

| Home (first name) | Age | Birthplace | Occupation (and property if listed) |

| – | – | – | – |

| – | – | – | – |

| – | – | – | – |

| – | – | – | – |

| – | – | – | – |

| Others in Household Home (first name) | Age | Birthplace | Occupation (and property if listed) |

| – | – | – | – |

| – | – | – | – |

| – | – | – | – |

| Street Adress: | House number: | ||

| Additional Biographical Information: | |||

| – | |||