Part II. How to Study Your Neighborhood

Field Trips

Richard Karberg

Field trips are an invaluable way to learn the history of a neighborhood. Far from being merely entertaining or time filling activities, they can provide an excellent means of building awareness of an urban environment for adults and children alike. But the most important part of any successful field trip is the planning. The organization of a field trip can be, however, just as complicated as preparing a European grand tour. And for this reason many people go to non-profit and commercial organizations for pre-packaged neighborhood tours. Many of these tours are excellent. Some can be customized, but usually these are more expensive, and even then they may not include all the points of interest needed to be truly informative.

Planning a field trip requires the organizer to have a clear set of objectives and a willingness to make arrangements to view both the well-known and obscure sites which are the objectives of your tour program. Hosts at sites to be visited as well as chattered bus companies demand that the organizer prepare a specific timetable and a precise routing. Most bus companies will provide a tour routing for you, but the tour routings you provide yourself are likely to be the most advantageous. In any event, a tour bus driver must know the route prior to departure, as one of the most exasperating parts of any tour is when the guide has to be directing the bus driver while trying to talk to the tour participants.

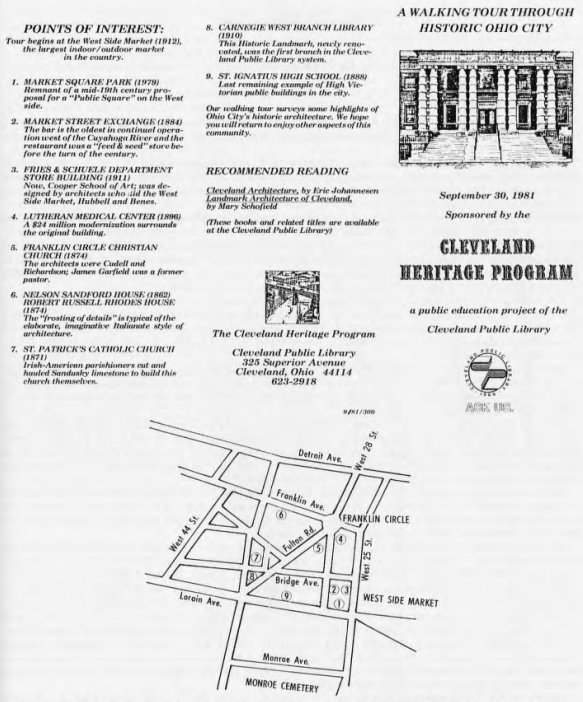

Likewise, a tour guide put together in advance of the trip is a very helpful tool for the participants to have as well as being useful in promoting the tour. Such guides will not only serve as informative background material for participants but can be helpful models for planning future tours. They can be printed like this guide, or reproduced by simpler means.

The tour arrangements, like the guide, should be prepared at least a month ahead of the tour. But even with advance arrangements, reconfirmation of details as the date approaches is essential. A tour repeated a month or so after its initial run needs to have all stops and routes reconfirmed. One should never assume these conditions will remain the same. Certain sites may not be accessible at the later date and some improvisation may become necessary.

A successful field trip should enable one to answer the following questions about a neighborhood:

- What does the neighborhood look like? What kinds of houses, stores, religious structures, schools, industries and other key landmarks are found in the area? Where are they located? When were they built? Who built them?

- What are the physical features of the area? What is the topography? Do rivers or lakes provide boundaries? Are there railroad tracks, freeways, or streets which demarcate the area?

- What remains of the structures which occupied the area in the past? Are there old buildings present? If so, how old and what is their present condition? Have their original purpose or use changed?

- What kinds of social activities are taking place in the area? Is it an area populated chiefly by older residents or are there lots of children? Is there a visible street life? Do people feel safe? Why or why not? How much neighboring goes on?

- What kinds of cultural life exist in the area? What institutions, public and private, are important for the community? What kind of commercial life does one notice? How well preserved are local buildings? What kinds of nationality culture exists?

The Heritage Program’s tour of the West Central area of the city of Cleveland is a good example of the kind of tour that can be offered to the public. It was difficult to arrange because of the existing conditions in the neighborhood. The West Central area of Cleveland is one of the oldest, most diverse and most changed communities. Initially it was the home of Irish and Germans, by the turn of the century it became the center of Cleveland’s Jewish community. Later Italians and other Europeans moved to the area and by the 1920s West Central became the site of Cleveland’s black ghetto. Urban renewal, freeways, and demolished buildings meant that by the 1980s very little remained of the area which had been one of the most diverse and interesting histories in the city. The Program was committed to touring the area but had to wait until sufficient research was completed in order that an adequate job could be done.

The tour centered upon the important buildings noteworthy in the transformation of the community from a primarily Jewish area to a black settlement. We selected five buildings—Shiloh Baptist Church, originally B’nai Jeshurun Synagogue, Triedstone Baptist Church, originally Oheb Zedek Congregation, St. John’s AME Church, and the Phillis Wheatley Association as places we would like to visit. Each of these institutions was contacted and a mutually acceptable time and date for the tour, a Sunday afternoon, since all the churches were open and had just concluded services by that time. Confirming letters were sent and each was followed up with a telephone call. The tour route was then made with special attention to other sites which would be viewed on the outside only: such buildings as Friendship Baptist Church, formerly the home of Tifereth Israel; The National Negro Improvement Association, formerly the Jewish Infant Home; Central High School; and the old Babies Dispensary. We selected these buildings because of their historical significance to the community.

Every neighborhood, regardless of the transformations that have taken place in it, can be made the fruitful subject of a tour. Some neighborhoods have deteriorated and may present logistical problems that require more work in arranging tours to these areas. Sometimes things about a neighborhood can be best seen by examining landmarks in an adjacent area. For example, in looking at the Broadway-Fleet area, a tour of Republic Steel’s nearby rolling mill even though it has changed since 1900 provides valuable insights into the industrial and economic base that was the original reason for this neighborhood’s existence.

Bibliography

Blake, Peter, God’s Own Junkyard: The Planned Deterioration of America. N.Y.: Holt, Rinehart and Winston, 1964.

Clay, Grady, Close-Up: How to Read the American City. N.Y.: Praeger, 1973.

Jackson, John B., American Space. N.Y.: Norton, 1972.

Lewis, Pierce, “Axioms of the Landscape: Some Guides to the American Scene,” Journal of Architectural Education, 30 (Sept., 1976), pp. 6-9.

Lively, Penelope, The Presence of the Past: An Introduction of Landscape History. London: William Collins.

Lynch, Kevin, What Time Is This Place? Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1972.

Quimby, Ian M., ed., Memorial Culture the Study of American Life. N.Y.: Norton, 1978.

Smith, Peter F., The Syntax of Cities. London: Hutchinson, 1977.

Watts, Mary T., Reading the Landscape of America. New York: MacMillan, 1975.

Wurman, Richard S., Making the City Observable. Cambridge, Mass.: MIT Press, 1971.