Part II. How to Study Your Neighborhood

Neighborhood Architecture

Richard Karberg and Jeanne Kish

A first look at a neighborhood will invariably consist of viewing buildings. Houses, stores, churches, factories are often the tangible and most enduring evidence of a community’s past.

Neighborhood architecture can be divided into two categories. One, the work of the name architects who were usually commissioned to design the churches, synagogues, schools, public buildings, the larger businesses and often the factories. The second category is vernacular architecture, usually the work of lesser known architects or the work of builders or laymen working from stock plans or plans of their own. Buildings in this category would include the smaller religious structures, homes of fraternal or social organizations, neighborhood businesses, smaller factories and houses.

Often the significant work of the important architects remains long after a neighborhood has gone through several transitions. The Shiloh Baptist Church, at 5500 Scovill Avenue, designed by Harry Cone as the B’nai Jeshurun Temple in 1906, is a good example. The work of architects of historically significant buildings is easier to research since their records are more likely to remain. Information about vernacular architecture is harder to find since correspondence and plans, if any existed at all, have usually not been preserved. Often the only records available may be building and/or zoning permits and purchase papers. Old photographs, insurance maps and oral histories can be important sources of information in such cases.

People interested in finding information about their houses should begin by consulting building permits, city directories, plat maps and insurance maps. Architectural repositories such as the Cuyahoga County Archives or the Western Reserve Historical Society may be searched if the building in question was designed by an architect with any sort of reputation.

The extent to which neighborhood buildings reflect the ethnic origins of their builders is debated. Some contend that immigrants brought with them the architectural traditions of their homeland and employed these traits in constructing their American homes. The opposite view holds that immigrants merely built according to the accepted customs of the area in which they settled and that any stylistic reference to the homeland was little more than a coincidence. An attempt has recently been made on Cleveland’s Southeast Side to replicate the architectural details reminiscent of chalets in the Tatra Mountains in buildings erected along Fleet Avenue in the period between 1880 and 1925.

Buildings themselves can be read for information about the neighborhood. Cleveland, like many northeastern cities, saw the construction of many two-to-three story blocks lining the main thoroughfares of its neighborhoods. Shops or businesses occupied the ground floor space, while offices and/or apartments occupied the upper floors. Between 1890 and 1930, such an arrangement enabled businessmen to run a business downstairs, live in an apartment upstairs and rent out the rest of the block to pay the mortgage and provide additional income. In some ethnic communities the expression “living in rent” referred to people who lived in these apartments situated above commercial establishments. Decorative elements found on these buildings sometimes reflect the ethnic origin of the builder, although an inscription on the cornice or a nameblock at some prominent location on the front of the building is often a better indication of which ethnic groups helped build up an area. Signs, advertisements, modifications of the original structure and other architectural details can provide further clues to the past usage of a building.

A close examination of gardens in these same communities, the selection of plants, their placement and overall design may sometimes be helpful in establishing the original homeland and the ancestral background of residents living in a neighborhood. Even today, for example, one need only walk along the west seventies north of Detroit Avenue or on the streets in Cleveland’s “Little Italy” to observe the grape arbors and gardens reminiscent of the Old World landscape design brought by the first immigrants from their native lands.

Housing stock can also reveal some things about a neighborhood. The development of a given style of housing from the late nineteenth century through the present follows a relatively consistent pattern for both single and multifamily dwellings in a given neighborhood.

Land use patterns are also very important. While, in most instances, the designs of individual houses reflect the styles that were current when the homes were built, the placement and number of houses on a lot may reflect something else. Up until the nineteen twenties, in many Cleveland neighborhoods the practice of placing two houses on a single lot was commonplace. The ownership of real estate was considered, among many ethnic groups, highly desirable, and the building of two houses so that half of one and the entire second house could be rented out, became a popular—and practical—means of entering the realm of property ownership. In other instances, such factors as the isolation of ethnic groups, the need to live close to one’s workplace, and poor transportation made the congestion of neighborhoods inevitable.

Consequently, phenomenon known as the “urban village” sprang up in many of our urban centers around the turn of the century. Houses were built on narrow lots huddled around community focal point such as a church, while industrial employment was often provided on the neighborhood’s periphery. To this extent, such neighborhoods in urban America resembled medieval European villages.

Complete lack of zoning in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries allowed for the haphazard development of land use. Commercial and residential usage was permitted without restriction and chicken coops, outhouses and other dependencies allowed to exist without benefit of building codes.

As we have seen, neighborhood architecture can provide valuable insights into communities within certain parameters. There is much confusion over what we mean by neighborhood architecture or ethnic architecture. Both terms are difficult to define. Indeed, the two often overlap.

Eric Johannesen, preservationist with the Western Reserve Historical Society, believes that it is virtually impossible to tell whether you are in a Slovenian neighborhood in the east sixties near St. Clair or a Hungarian neighborhood in the east hundreds near Buckeye. But he feels there is generally a commonality of form to be found in the buildings of a neighborhood.

Cleveland’s West Central Area

Indicative of what can be found elsewhere, there are several buildings in Cleveland’s West Central area that when examined reveal the history and social transition of this community from a residential neighborhood of the city’s elite to one serving the social and institutional needs of recent immigrant and migrant groups.

In 1880, Jacob Goldsmith, a partner in the firm of Koch, Goldsmith, Joseph and Feiss, which later became the important Cleveland clothing firm of Joseph and Feiss, built a house on East 40th Street (then known as Case Avenue). The house is attributed to Cudell and Richardson, important Cleveland architects of that period. Its exterior reflects an Italianate style while the inside details are Eastlake in design.

Case Avenue during this period was a fashionable street. It was not as grand as Euclid Avenue, but, nonetheless, it was an area where the more recent arrivals to the city who made a successful living such as German Jewish merchants and manufacturers would build their new homes. Goldsmith was a prominent member of Cleveland’s Jewish community and became a director of the Jewish Orphan Asylum on Woodland avenue, also designed by Cudell and Richardson. The Goldsmith home reflects the then current taste in design.

The changing uses to which the house was subsequently put reflect some of the transitions which took place in the neighborhood and the city from 1880 to 1930. As the old line German-Jewish community moved eastward, the West Central area was occupied by newer Jewish immigrants from Russia and Eastern Europe. The German-Jewish community built institutions to assimilate and provide services to the new arrivals in the neighborhood. The Goldsmith residence housed the Jewish Infant Home until 1923. When blacks became the majority population group in the neighborhood, the building became the home of the National Negro Improvement Association. The structure has thus witnessed a number of changes and developments in the community and it is a good example of how historical research on buildings can throw light on the ethnic and social transitions and transformations of a community.

St. John African Methodist Episcopal Church dates from 1830. The congregation met in a number of private homes before it built the present church in 1908 on East 40th near Central. The structure exemplified the period’s typical Protestant church design by employing features of English Tudor architecture on the exterior. The interior of the church is an example of the Akron plan, which provided for a sanctuary and Sunday School assembly space and classrooms with the two areas separated by a folding wall. There is nothing in either the external or internal features of the building to indicate the precise kind of congregation which occupied it. The building indicates instead what other church buildings in the city built around this period looked like and provides another type of continuity with the past. While the church has remained at this site, its congregation today reflects a new trend in black church membership. Most members of St. John’s are long time Clevelanders. Although many now reside in the eastern suburbs or more affluent city neighborhoods, they maintain membership in the church that served their ancestors.

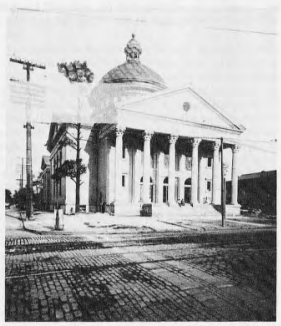

In 1906, the congregation of B’nai Jeshurun moved from Eagle Street to a new building on east 55th Street. The structure designed by Harry Cone represents the then current neo-classic style. The outstanding feature of the synagogue, which is visible from a long way off, is the dome capped by a gilded cupola that was originally topped by a Star of David. The inside of the dome is equally impressive as it houses a large stained glass ceiling which is the focal point of the building’s interior. The large balcony and stained glass windows have been retained. This synagogue was one of three important religious structures in Central-Woodland on a short stretch of East 55th Street, the others being the home of Tiffereth Israel Congregation and Epworth Church.

The structure remained the home of B’nai Jeshurun until 1925 when the congregation moved to a new home on Mayfield Road in Cleveland Heights known as the Temple on the Heights (and which was in turn abandoned a few years ago for a new home in a still farther eastern suburb). The building on East 55th then became the home of Shiloh Baptist Church, whose congregation had been formerly located on East 30th Street between Scovil and Woodland Avenue.

The religious transformation of this building represents a central pattern not only in the Central-Woodland area of Cleveland but in many other inner city neighborhoods across the United States. The change in building ownership reflected neighborhood transition. As the Russian Jewish residents of the nineteen twenties began moving out to the Mount Pleasant and Glenville areas, they were replaced by blacks pouring into Cleveland from the American South—a pattern that would be repeated in other areas on the city’s East Side during the nineteen fifties and nineteen sixties as whites moved to the suburbs.

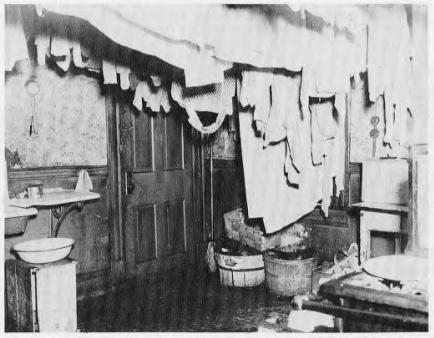

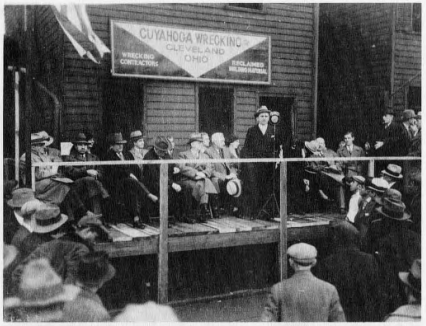

The decline of this community was reflected in many of the homes of the area, which deteriorated as a result of overcrowding, lack of maintenance and cheap construction methods. Elegant houses as well as smaller workers’ cottages and tenements all went through the same process of being overcrowded, subdivided and neglected. Finally, in the early nineteen thirties an attorney and Cleveland City Councilman named Ernest J. Bohn developed the Cleveland Metropolitan Housing Authority, a new agency that would be responsible for slum clearance and the establishment of public housing throughout the city.

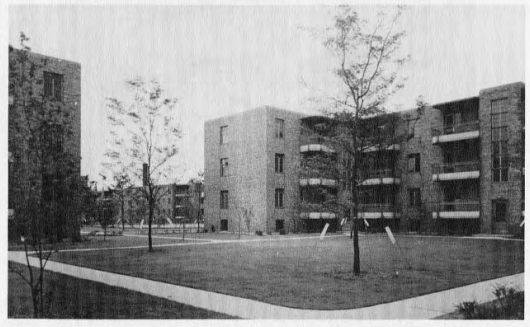

In June of 1934, the Public Works Administration (PWA) provided funding for Cleveland’s first public housing project, Cedar-Central Estates. The units at Cedar-Central consisted of pairs of six-room apartments in three-story brick buildings grouped around a central courtyard. Many apartments featured art moderne balconies. Individual units featured tile bathroom floors, and kitchen fixtures included refrigerators and gas stoves. Each unit was heated by steam heat supplied from a central power plant, and a limited number of garages were built.

The Estates attracted a large number of visitors and applicants for the apartments after it opened in 1937, accompanied by extensive social service projects developed for its residents. A sense of community was quickly developed and pride was reflected in the neighborhood newspaper, The Cedar Centralite, published into the nineteen fifties. During and immediately after the Second World War, the Cedar Central Estates became a national model for the belief that a decent living situation was possible under public housing administrations. Sadly, the subsequent loss of funds by the Cuyahoga Metropolitan Housing Authority and the gradual erosion of city services eventually brought about the physical deterioration of the Cedar-Central Estates and the further decline of a once recovering neighborhood.

The newest development in the area has been the Metropolitan Campus of Cuyahoga Community College, which was constructed in 1966, three years after the founding of the college in 1963, on a parcel of land situated in the St. Vincent’s Urban Renewal area. The original plans drafted for this area in the late nineteen sixties called for the construction of middle class housing which never materialized. The firm of Guenther, Outcault, Bonebrake and Rhode was hired to design the new campus—originally conceived of as a loosely connected series of buildings much like those that would be found on a small rural college campus. But the plans were soon revised, resulting in the building of fewer units linked together by a colonnade with a central courtyard as the focal point.

One can see from this study that neighborhood architecture is concerned with many things. Building size, style, use and even the placement of a structure or structures on a site are all important considerations. While this relatively new field is still largely unexplored, the close examination of neighborhood architecture would clearly be an important contribution to the study of neighborhood and community history in Cleveland and other cities in the United States.

Bibliography

American Institute of Architects, Cleveland Chapter, Cleveland Architecture, 1796-1958. N.Y.: Reinhold Publishing Corp., 1958.

Andrews, Wayne, Architecture in America: A Photographic History From the Colonial Period to the Present. N.Y.: Atheneum, 1977.

Bach, Ira J., Chicago on Foot: Walking Tours of Chicago’s Architecture. Chicago: J.P. O’Hara, 1973.

Benedict, Paul, Historic Site Interpretation: The Student Field Trip. Nashville, Tenn.: American Association for State and Local History, 1971.

Boatright, Claudia R., Shaker Heights: The Van Sweringen Influence. Kent, Ohio: University Printing Service, 1981.

Brunskill, R. W., Illustrated History of Vernacular Architecture. N.Y.: Universe, 1971.

Campen, Richard N., Architecture of the Western Reserve, 1800-1900. Cleveland: Press of Western Reserve University, 1971.

——–., Ohio—An Architectural Portrait. Chagrin Falls, Ohio: West Summit Press, 1973.

Caudill, William, et al., Architecture and You: How to Experience and Enjoy Buildings. N.Y.: Watson-Guptill, 1978.

Chambers, S. A., What Style Is It. Washington, D.C.: Preservation Press, 1977.

Chapman, Edmund, Cleveland: Village to Metropolis. Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society, 1981.

Danzer, Gerald A., “Buildings as Sources: Architecture find the Social Studies,” High School Journal 57, No. 5 (1974), pp. 204-213.

Ellsworth, Linda, The History of the House and How to Trace It. Nashville, Tenn.: American Association for State and Local History, 1976.

Federal Writers Project, The Ohio Guide. N.Y.: Oxford Press, 1940.

Goldfield, David, “Living History: The Physical City as Artifact and Teaching Tool,” History Teacher 8. No. 4 (1975), pp. 535-556.

Grow, Lawrence, Old House Plans. N.Y.: Universe Books, 1978.

Hitchcock, Elizabeth, G., Jonathan Goldsmith: Pioneer Master Builder of the Western Reserve. Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society, 1980.

Hitchcock, Henry R., Architecture: Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries, N.Y.: Penguin, 1977.

Johannesen, Eric, Cleveland Architecture, 1876-1976. Cleveland: The Western Reserve Historical Society, 1979.

Kidney, Walter, The Architecture of Choice: Eclecticism in America. N.Y.: George Braziller, 1947.

Lynes, Russell, The Tastemakers. N.Y.: Universal Library, 1954.

Maass, John, The Ginger Bread Age: A View of Victorian America. N.Y.: Bramhill House, 1957.

Mansell, George, Anatomy of Architecture. N.Y.: A & W Publishers, 1979.

National Trust for Historic Preservation, America’s Forgotten Architecture. N.Y.: Pantheon Books, 1976.

Quimby, Ian M., Material Culture and the Study of American Life. N.Y: Norton and Co., Inc., 1978.

Ridley, Anthony, At Home: An Illustrated History of Houses and Homes. N.Y.: Crane Russak, 1976.

Rifkind, Carole, A Field Guide to American Architecture. N.Y.: New American Library, 1980.

Sande, Theodore, Industrial Archaeology: A New Look at the American Heritage. N.Y.: Penguin Books, 1978.

Schofield, Mary P., Landmark Architecture of Cleveland. Pittsburgh, Penn.: Ober Park Associates, 1976.

Scully, Vincent, American Architecture and Urbanism. N.Y.: Praeger, 1969.

Tunnard, Christopher, et al., American Skyline. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1955.

Western Reserve Historical Society, The Architecture of Cleveland; Twelve Buildings, 1836-1912. Cleveland: Western Reserve Historical Society; Historic American Buildings Survey, 1933.