Part IV. Case Studies

The Architecture of Cleveland’s Immigrant Neighborhoods

Eric Johannesen

From time to time it has been suggested that the architecture of the immigrant neighborhoods in a nineteenth century industrial city like Cleveland took on or achieved a distinctive national character. So far very little convincing evidence has been shown to substantiate this notion. In a few individual buildings, especially the churches, a national character may be discovered. And it is still worthwhile to ask the question: to what extent are the culture, the ideas and the style of immigrant nationality groups reflected in the buildings by and for them?

For some kind of answer to this question, I think we may look at three areas: first, buildings designed by architects who were themselves immigrants from other countries; second, buildings erected for specific uses in the social life of the ethnic community or neighborhood; and third, buildings designed at the time when symbolism was a fundamental element in architecture, or in other words, when national styles were consciously borrowed for their associations in order to symbolize or represent an idea.

Two architects of European origin in particular are known to have designed a great many buildings in Cleveland from the 1870s to the 1890s. They were Franz Cudell of the partnership of Cudell and Richardson, and Andrew Mitermiler. Cudell was German and Mitermiler, Bohemian. Cudell’s partner John Richardson was a native of Scotland, while Franz Cudell was born near Aachen, Germany, and lived there until he emigrated at the age of twenty-two. Cudell came to Cleveland in 1867 and formed the partnership with Richardson in 1870. It seems clear that Franz Cudell was steeped in Gothic, German and Dutch architecture (the municipal boundaries of Aachen are on the frontiers of Holland and Belgium). This is especially evident in two Cleveland churches designed by Cudell and Richardson in the 1870s. Some might dispute the use of the label “Victorian Gothic,” but in any case, it refers to a style containing noticeably more elements from Italy, Germany and France than did the earlier nineteenth century Gothic Revival, which was predominantly English in origin.

The two churches in question were designed for the Catholic Diocese and erected for German-speaking congregations. The first Bishop of Cleveland had been opposed to the institution of foreign language parishes but was finally persuaded of their necessity. St. Joseph’s, the second German Catholic parish on the East Side, was organized in 1858. The cornerstone of the Cudell and Richardson building was laid in 1871. The Cleveland Leader of October 23, 1871, stated that “this will be the first clerestory church ever built in this city”—refering [sic] to the presence of windows in the upper part of the apse or dome. The structure was dedicated in 1873, but the steeple was not completed until 1899. The facade of St. Joseph’s, located at Woodland Avenue and East 23rd Street, is the most characteristically German of Cudell and Richardson’s churches, which rises the full height of the center bay and includes three entrances and a steep hipped roof. The interior, however, is a three-aisled hall with an aisle arcade, a blind triforium and the clerestory, an arrangement which was more typical of the French Gothic. The three-sided apse featured tall clerestory windows which flooded the interior with light.

St. Stephen’s was the second parish created to serve the German-speaking Catholics on the West Side. Founded in 1869, the parish conducted its worship in a small brick church for six years. The cornerstone of the present church, located at 1930 West 54th Street, was laid in 1873, and the edifice dedicated in 1881. The large cruciform building, constructed of Amherst stone, is massive and permanent in appearance. The interior features no clerestory, but the aisle arcade is taller, and the proportion of open space to the supporting columns is much greater, creating the general effect of a German hall church. The height of the ceiling is seventy-five feet, which compares with some of the early cathedrals of Europe and is most impressive for a Mid-western American parish church.

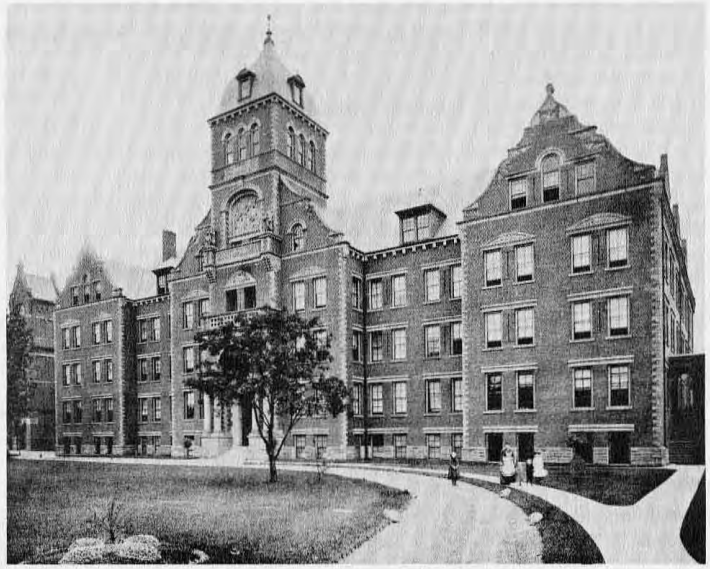

The Jewish Orphan Asylum, designed by Cudell and Richardson and erected in 1888, was a large three-story brick building with a five-part facade, concave-convex gables and a tower with a bell-shaped roof, all of which suggest a definitely Dutch or Northern Renaissance character. The arched entrance portico on coupled Ionic columns revealed considerable sophistication and an awareness of European architecture. The Orphan Asylum was founded in 1868, and the complex eventually included the large main building, a school and a number of utilitarian outbuildings. The location on Woodland Avenue near East 55th Street lay at the eastern edge of the Jewish settlement at that time.

Portions of this essay have been previously published in the author’s Cleveland Architecture, 1876-1976 and are reprinted by permission.

The tradition of the immigrant architect as ethnic architecture: Cudell and Richardson’s Jewish Orphan Asylum. (Courtesy of Western Reserve Historical Society)

These three buildings, in spite of their differences, suggest that Cudell, who is credited with their design, found his youth in Aachen, Germany, an unforgettable influence.

Victorian Breweries and Renaissance Churches

Andrew Mitermiler was a Bohemian-born architect who designed breweries, Bohemian and German social halls and institutions, as well as commercial blocks. Mitermiler’s advertisement in Leading Manufacturers and Merchants of Cleveland in 1886 states:

He is recognized as a thoroughly representative member of the distinctive American school of architecture, and has solved and still is successfully solving the complex problem of how to best utilize the minimum of the building area with the maximum of accommodation and architectural beauty of design.

The store Mitermiler built for Otto F. Lohman, a German druggist or apothecary, on Woodland Avenue at East 84th Street in 1885, is a good example of the general stylistic tendencies of American commercial architecture in the 1880s. The same may be said of his Zverina Block on Broadway, built in 1889. Mitermiler’s Leisy Brewery, a West Side landmark located on Vega Avenue, was a fairly standard Victorian structure, though many architects of breweries often strove for the effect of a medieval castle. (The last remnant of the Dieboldt [sic] Brewery at 2702 Pittsburgh Avenue, S.E., which was demolished in 1980, is a good example).

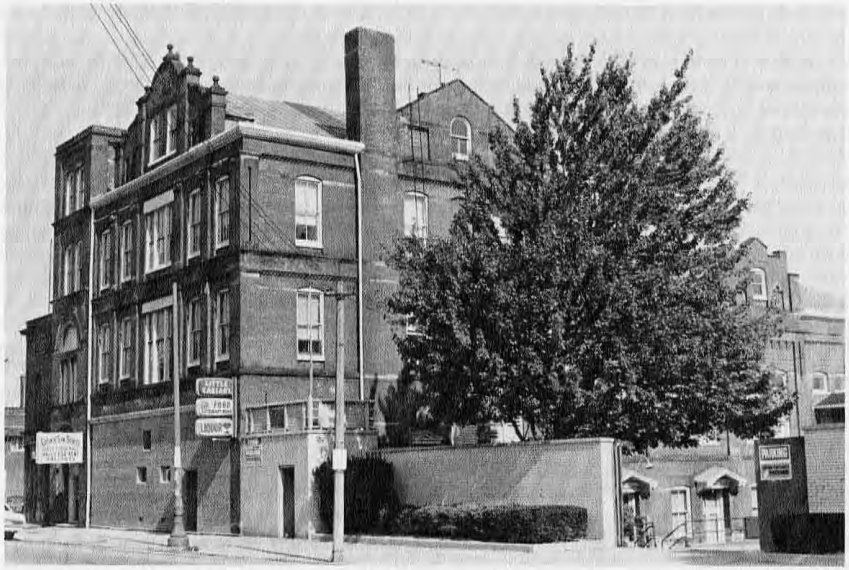

The building for community social use as ethnic architecture: Hungaria Hall (Czech Sokol Hall). (Courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society)

However, a social institution like the German Home for the Aged exhibits some European characteristics. The Altenheim Association was organized in 1875 by the West Side Deutscher Frauen Verein, and the cornerstone for its Home for the Aged was laid in 1891. The steep roofs and the solid curved balustrade of the Altenheim suggest its German origin. Mitermiler himself also designed the Hungaria Hall, which has a Middle European Renaissance flavor because of its concave-convex gables. This hall and wine garden, built in 1890, was managed and conducted by the Royal Hungarian Government of Budapest under the supervision of the Royal Ministry of Agriculture, as a social hall and auditorium with outdoor park and dancing pavilion. It remained the Hungaria Hall until about 1906, and has been the home of the Czech Sokol Hall since World War I.

Another social hall also shows the increasing awareness of European styles Mitermiler shared with most of the other architects of his day: the Bohemian National Hall on Broadway, which was to become a center for liberal minded Czechs, its auditorium used for speakers, plays, concerts and operas for years. A group of forty Czech societies contributed to building the hall, and initial plans had been prepared by Mitermiler and John Hradek, another Bohemian architect. In 1895, however, because the cost of the building was estimated at $60,000, construction was postponed, and in 1896 Mitermiler died. Later the same year, new plans were prepared by architects Steffens, Searles and Hirsh, and the building was completed in 1897. The style of the hall contains elements of the Romanesque and Renaissance styles. The auditorium occupies the two middle floors of the four-story structure. The large proscenium stage, flanked by two levels of box seats, is ornamented in the Renaissance style. Scenery built for various stage and operatic productions is still intact, and the main curtain is painted with a view of Prague.

In other cases too, the owners and builders were directly responsible for the European style of their building. In the early 1880s the German neighborhood on the Near West Side was considered for the site of a Catholic college and preparatory school for the City of Cleveland. The Fathers of the Jesuit German Province of Buffalo took charge of St. Mary’s parish on West 30th Street for this purpose in 1880. The project was approved, and St. Ignatius College opened in 1886. Two years later, the north wing of the current five-story brick building was erected on Carroll Avenue, and the southern wing on West 30th Street was added in 1890-1891. The plans for the building are said to have been prepared by one Brother Wipfler of the Jesuits, who was sent from Europe for this purpose. The building, which became St. Ignatius High School after the college was separated and became John Carroll University in 1923, is an unusually fine example of High Victorian Gothic style, the only distinguished one surviving in Cleveland apart from the churches. However, certain details, specifically the corner turrets and eyelet dormers of the main tower, give St. Ignatius High School a definitely German flavor appropriate to its original occupants, its architect and its neighborhood.

The dedication of St. Stanislaus Church in the Polish community located at East 65th Street and Forman Avenue took place in the same year as the completion of St. Ignatius. It was one of the most extravagant churches of the decade. The account of its dedication in November 1891 set its cost at $250,000. According to an Engineering News Record Index, the equivalent building cost in 1970 would have been something like $4,800,000. At the time St. Stanislaus was admittedly one of the poorest parishes in the diocese. The architect was William H. Dunn, who had worked in the office of Levi Scofield and had served for a time as city building inspector. The large brick church is yet another example of Victorian Gothic, based in part on East European prototypes. Originally spires on the two towers reached to two hundred thirty-two feet, but they were destroyed in a windstorm in 1909 and the upper stages were rebuilt in their present form as crowned belfries.

‘The greater part of the expense was lavished on the interior, however. The stained glass windows, combining pictorial art with abstract floral and geometric designs, incorporate a comprehensive and complete iconographic scheme, unlike the partially finished programs of many churches. But the major glory is to be found in the carved wooden furnishings, rivalled only by some parts of St. Stephen’s. The central altarpiece is an architectural construction, with life-size polychrome figures mounted in the niches of a framework which culminates in a steepled superstructure. It was based on similar works in the medieval style in churches such as the one in Cracow, Poland, and the richness of the total impression reveals a love of craftmanship and ornamental effect unknown to later generations.

The Two-and-a-Half Story American Dream

As we turn from the buildings serving the social needs of the community to residences, however, it is difficult, if not impossible, to find any carryover from the Old Country. One characteristic linked the greatest mansion and the poorest immigrant house. This was the commitment to the detached, one-family dwelling, which European critics found to be one of the most distinguishing traits of American architecture. The new populations seemed determined to become American as soon as possible, and while Old World customs and some craft traditions continued, the people built in the local style of the time, whatever it might be.

In the old Ohio City area, where the original inhabitants were chiefly Irish and German before the Civil War, most of their houses were done in the common vernacular building style, either frame houses with a simple gabled outline and a small stoop or side porch, or brick with stone lintels over the doors and windows. These are the same houses which were being built on the East Coast and even in the Western Reserve rural countryside. In the second half of the nineteenth century, many houses in the various neighborhoods were done in the Gothic, Italianate, and Queen Anne styles, with ornamental detail rendered in the jigsaw and lathe of the carpenter-builder. The building lots were very narrow, but it is significant that the ideal of the detached house was retained; here there were no row houses in the manner of Eastern cities like Philadelphia or Baltimore. Most of the houses were planned by the carpenter-builders, sometimes calling themselves architects, or by the owners themselves.

Around the turn of the century, the new immigrant found neighborhood housing which was in 1900 already being criticized by the Cleveland Architectural Club:

Since 1885 a building, not architectural, feature has developed, which . . . is not indigenous, not confined to Cleveland, i.e., the real estate “buy a home on a monthly payment” house. The idea is all right, but why is it necessary to line street after street with ill designed, poorly constructed, gaudily decorated, duplicate houses, for which the unsuspecting investor pays a comparatively big price?

The pattern of platted subdivisions (usually no more than a few streets in one direction and three or four blocks in the other) is familiar. Duplicate or nearly identical houses were erected on speculation and sold on a mortgage. They line the streets, row upon row, literally by the thousands, but these houses fulfilled a portion of the “American Dream” of equality.

Almost without exception the developer’s houses were wooden. The typical one was two-and-a-half stories tall with its gable end facing the street and a front porch of one or two stories. Later houses tended to be two-family residences with identical floor plans on each story, which enabled the property owner to become an investor and a landlord. This type of income-producing house became enormously popular and could be found endlessly duplicated in every new subdivision. But it is virtually impossible today to tell whether you are in a Slovenian neighborhood of the East Sixties near St. Clair or the Hungarian neighborhood of the East Hundreds near Buckeye.

The Language of Buildings

After the turn of the century, American architecture everywhere entered a period of more “archaeological” eclecticism. In other words, styles were freely borrowed from every period in history and used in a symbolic fashion. Banks and cultural institutions were classical; churches were Gothic; and homes were done in styles which symbolized gracious living, such as Colonial, English or French. The availability of such styles and the currency of this attitude had an obvious application for national communities. Thus the Holy Rosary Church in Little Italy is Italian Baroque in style. Of course, the Italian Baroque was not only a national style, it was also the style of the Catholic Counter-Reformation. The second decade of the 20th century was a period during which the American Catholic church was reaffirming its allegiance to Rome, and Cleveland had its first bishop to have been consecrated in Rome, Bishop Farrelly. Although immigration had peaked before 1910 and practically come to a halt with the outbreak of the First World War, the proportion of foreigners or first generation Americans in Cleveland’s population was larger than it had ever been, and in Catholic communities it was probably even higher. During Bishop Farrelly’s episcopate the Poles, Bohemians, Slovaks, Hungarians, Italians and other groups all built newer and larger churches.

The readily apparent feature shared by Catholic churches of the decade was the Baroque facade with two symmetrical towers consisting of open belfries with cupolas. This pattern rendered in stone could produce a truly Roman effect. St. Colman’s Church, 2027 West 65th Street, was designed by an Akron architect, for an Irish parish. Built during the war years of 1914-1918 with Indiana limestone, it has a monumental two-story facade with doubled Corinthian columns flanking the entrance. Guarding the flight of steps are the traditional sculptured winged characters symbolizing the Four Evangelists. In conception, scale and detail, St. Colman’s is among the most Roman of churches.

Almost as impressive though, is the facade of St. Elizabeth’s Magyar Church at 9016 Buckeye Road. Built in 1918-1922, as the second building of the first Hungarian Roman Catholic Church in the United States, St. Elizabeth’s was designed by Emile Uhlrich, a French-born architect. Its facade is unusually wide, a fact which is cleverly disguised by the concentration of the entrances in the center and by the handling of the towers. The interior space has some features of the basilican plan, but it is less an aisled nave than a large square auditorium with a colonnaded center aisle. In essence, the openness and width of the interior have the clarity of a classical space, and the Baroque elements are largely decorative.

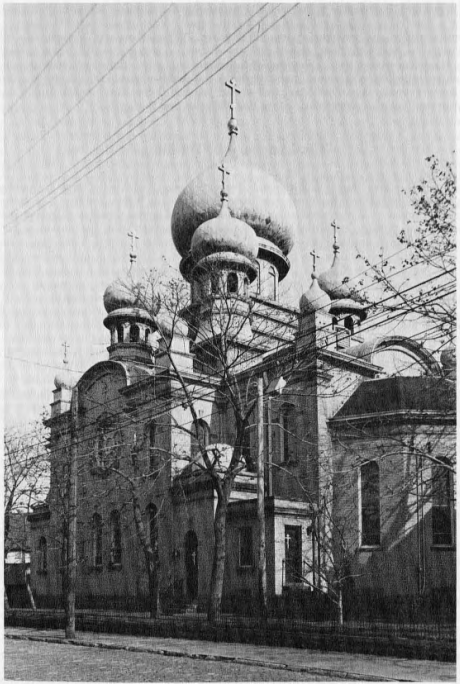

The churches of the Eastern faiths were even more likely to utilize an eclecticism in which the meaning of the building was specifically represented by a symbolic style. The Greek Church of the Holy Ghost is Byzantine, for example. Located on Kenilworth Avenue near West 14th Street in the Tremont neighborhood, it was built in 1909-1910. The Byzantine references include the twin facade towers with onion-shaped domes and a similar but smaller dome over the sanctuary. The interior with its elaborate iconostasis is even more Byzantine in character.

St. Theodosius Russian Orthodox Cathedral, erected at 733 Starkweather Avenue in Tremont in 1911-1912, is one of the best known of the immigrant churches. The impressive external silhouette of its thirteen onion-shaped cupolas has long been a familiar visual landmark on the high land above the Flats. The building is said to have been designed with features adapted from the Church of Our Savior in the Kremlin, in Moscow. The design was the result of the collaboration of Father Basil Lisenkovsky and Frederick C. Baird, a Cleveland architect. St. Theodosius has been recognized nationally as a most characteristic example of traditional Russian monumental architecture.

On the other hand, the Jewish synagogue, having no specific architectural tradition, was later in developing a style than temples of the other faiths. In the nineteenth century American synagogues were Gothic or Romanesque according to the fashion for Christian churches. In the early twentieth century a synagogue might be classical in style, as in the temple of Cleveland’s Conservative B’nai Jeshurun Congregation, which moved from its Eagle Street Synagogue to a new temple at East 55th and Scovill in 1906. This Neo-Classic temple has a portico of six Corinthian columns and a golden cupola and lantern on a Roman dome and drum. The use of the classical style in religious structures was generally meant to symbolize rationalism and enlightenment, and it is interesting to speculate whether the style was purposely chosen by the Conservative congregation as being more appropriate to its beliefs in comparison with those of an Orthodox temple.

The use of national eclecticism as ethnic architecture: St. Theodosius Russian Orthodox Cathedral. (Courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society)

The builders of synagogues later turned to the styles of Syria and the Near East because that region had been the birthplace of Judaism. A simplified and modernized Byzantine style was chosen for the Temple Tifereth Israel when it moved from East 55th Street to University Circle in 1924. The narrow triangular piece of property there required an unusual planning solution, and the architect, Charles R. Greco of Boston, devised a seven-sided plan with a circular dome. The Neo-Byzantine design is an interesting set of variations on the arched forms typical of that style. The round arch provides the basic motif for all of the forms, both structural and decorative used in the Temple building. The interior walls are made of precast blocks decorated with curvilinear Near Eastern abstract patterns. Yet the Temple is much more simplified than many eclectic Byzantine buildings. In fact, the severe geometry of the central mass and twin entrance towers resembles the stripped-clown forms of some Art Moderne designs of the twenties and thirties.

E Pluribus Unum

Perhaps the most comprehensive example of national symbolism is contained in Cleveland’s unique series of cultural gardens in Rockefeller Park, recognizing the contributions of various nationality groups to the life of the city. Connected by paths, they form an integrated chain symbolizing the fusion of the distinct nationalities into one American culture. The group of gardens was one of the last examples of the once popular custom of commemorative landscape architecture which had its roots in the nineteenth century. Begun in 1926, the project continued throughout the Depression years and was not completed until the eve of the Second World War. The idea of a series of gardens had been conceived with the creation of the Hebrew Garden in 1926. The Cleveland Cultural Garden League was established under the inspiration of Leo Weidenthal, editor and publisher and by the year 1930 German and Italian gardens had also been completed. A unified plan was prepared, with walks connecting the various gardens and in 1939 the series of eighteen was dedicated as a unit.

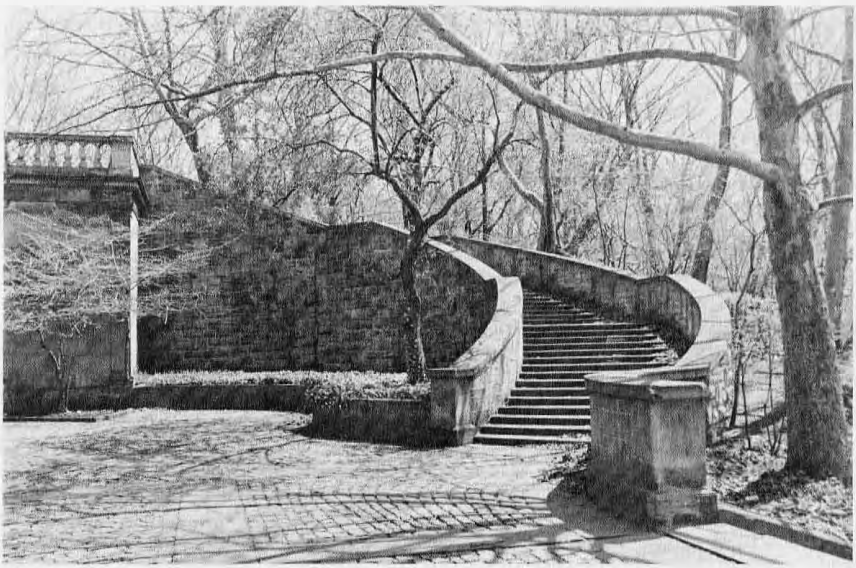

The use of commemorative symbolism as ethnic architecture: The Italian Cultural Garden. (Courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society)

Housing the American Dream: the architecture of assimilation. (Courtesy of the Western Reserve Historical Society)

The Cultural Gardens combine elements of formal planning from the Italian and French traditions with the more informal English practice. The majority of them feature an axial or centralized plan, with paved terraces and commemorative sculpture. From the point of view of the nationality groups, the commemorative sculpture—representing scholars, authors, poets, artists, and national heroes—was an essential part of the plans. A few of the plans display an obvious and specific symbolism, such as the six-pointed star of the Hebrew Garden and the Celtic cross of the Irish Garden. A general pattern is also discernible, in that the gardens of the Slavic and Eastern peoples are centralized, while those of the Latin and Western European groups are axial or cruciform. Some gardens are very European in flavor; especially notable in this respect are the Italian Garden’s long esplanade ending in a circular fountain and overlook, the curving Baroque staircases to the lower boulevard in the Lithuanian Garden, and the sunken rectangular patio framed by Tuscan columns in the Greek Garden. A few of the plans were laid out by European architects from the respective nations, but several Cleveland landscape architects were also responsible for designs. With their combination of formal architectural elements, organic landscaping and commemorative sculpture, the Cultural Gardens represent a unique effort at integrated and symbolic landscape architecture.

In the ethnic neighborhoods of Cleveland, then, there were buildings designed by immigrant architects; there were buildings planned to house the religious, educational, social and recreational activities of the immigrants; there were buildings whose style was chosen for its national associations; and there was the commemorative symbolism of Cleveland’s unique Cultural Gardens project. These, more than the common domestic and commercial architecture, may provide some lasting physical reflection of the presence of the immigrant communities in Cleveland.