|

|

|

|

|

|

|

July 1. While Mr. Harries was packing up to-day for his Northern trip, I came upon his journal, one which he kept several years ago, and obtaining his permission, I have read a part of it. In fact nearly all. I have concluded to write a journal too. I don’t know how long I shall stick to it, but I shall try and not give it up too soon.

Mr. Harris left this evening, on the 7 o’clock train for Fayetteville. From Fayetteville he intends to go to Cleveland, Ohio (my birthplace).

The Journals of Charles Chesnutt, Volume One

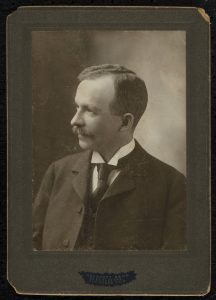

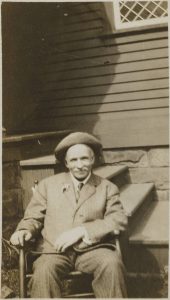

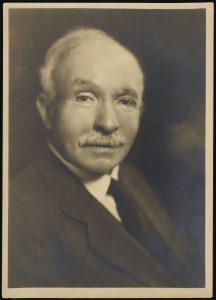

In the world of engaged learning, teachers are inspired by students. I teach primarily classes in African American literature, many of which answer requirements for General Education credit. Because General Education enrollment consists of students from colleges across the university, I have the opportunity to introduce a diverse group of students to the works of Charles Chesnutt, whom I describe as “the most famous Cleveland writer you’ve never heard of.” Inevitably, despite their diverse academic majors, all agree that what they are learning needs to be shared with teachers in the Cleveland Metropolitan school system. Yet while there are numerous websites devoted to Charles Chesnutt, few pay more than passing attention to his association with Cleveland, where Chesnutt was born in 1858, returned in 1883, built one the city’s most successful court reporting businesses, and wrote continuously until his death in 1932.

For the most part, critical discussions of Cleveland connections are limited to the Groveland stories, a fictitious locale modeled on Cleveland at the turn of the century, and, more recently, The Quarry, Chesnutt’s final novel, largely viewed as autobiographical. Arguably, Chesnutt’s Northern fiction is some of the most difficult to teach, in part because Chesnutt himself presents a challenge to the idea of the “race novel.” Because he was light-complexioned African American who could pass for white, critics often imply that Chesnutt was a writer who attached himself to the race novel as a trend in American literature. Teaching Chesnutt’s Northern fiction presents a particular literary challenge. Encapsulated in a Midwestern tone, Chesnutt’s writing about race did not let the reader know what he or she was reading was about race. Complicating matters more is Chesnutt’s satiric perspective in narrating the state of American politics and race relationships in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

What the “Cleveland Challenge” proposes is a shift in perspective, a shift that would broaden the context within which the Northern fiction stories can be taught. Such a shift departs from the usual approaches of personality and politics to one that frames Chesnutt and his work in multiple contexts. In other words, the Cleveland Challenge is less interested in examining Chesnutt’s works as literary criticism than establishing connections through methodologies that engage local interests, cultural contexts, and close reading skills. For example, critics and biographers note Chesnutt’s rise from teacher to principal at such a young age, but none investigate the circumstances that would allow (especially) a person of color to prepare for such advancement. Viewed from this perspective, how can we consider Chesnutt’s accomplishments as a writer without considering the education that allowed him to take advantage of such circumstances? An examination of Chesnutt’s early education in Cleveland provides a means to explore the larger history of education for people of color in America, as well as the impact opportunities for education in Northeast Ohio shaped Chesnutt shaped the development of Chesnutt’s Northern fiction.

Chesnutt’s mastery of satire and satirical perspective is undisputed and nowhere is Chesnutt’s mastery of light satire more acknowledged than in the Groveland stories, where characters both black and white living in the urban north at the turn-of-the-century encounter racist thoughts and behaviors typical of post-Reconstruction America. Investigating these stories in the context of the Cleveland Challenge demonstrate connections between Chesnutt’s mastery of satiric perspective and Cleveland’s influence on the author’s unique education. Chesnutt himself provides his first clue in the passage at the beginning of this chapter. The Mr. Harris to whom he refers in the first sentence is Cicero Harris, who, along with his brother Robert, not only shaped Chesnutt’s education, but that of black education in the state of North Carolina. As for the aforementioned journal, not only will Chesnutt stick to the chronicles he begins on July 1st, he will maintain entries from 1874 to 1881, recording thoughts and experiences on which he will build lifelong learning. From the first journal, we learn almost immediately that Chesnutt’s intention is to acquire a university education. We learn that he spends most of his free time preparing for entrance exams and studying subjects required for entrance to university studies. We learn such preparation includes the study of history, literature, French, and German. We also learn that the study of Greek and Latin, the languages of classical Western civilization, are essential for access to higher education. We learn that, self-taught, Chesnutt becomes fully versed in the Western tradition. We learn that his favorite subject was Latin and that, of all his studies, Latin has had the most impact. He writes:

I do not think that I will ever forget my Latin. The labor I spend in trying to understand it thoroughly, and the patience which I am compelled to exercise in clearing up the doubtful or difficult points, furnishes it seems to me, as severe a course of mental discipline as a college course… (Journals, p.92)

Latin was the language of Greek and Roman literature, which was the literature that inaugurates satire as a literary genre in Western culture. It would not be idle speculation, therefore, to assert that Chesnutt’s mastery of satire and satirical perspective is directly related to his love of Latin or that his love of the language would include an acquaintance with the literature written in the language he loved. For our purposes, however, using satire as the platform for teaching the Northern stories does not require Chesnutt’s love of Latin. Rather, Part Two: “Teaching the Northern Stories,” offers guidelines that provide explanations of the fundamental types of satire, as well as study guides to more broadly understand Chesnutt’s use of satiric perspective. Such an approach helps to engage discussion by framing connections between social, economic, political, and cultural influences to offer new insights and deeper appreciation of the way the stories crafted.

Approaching The Quarry through the lens of the Cleveland Challenge moves away from autobiography to demonstrate the impact of Chesnutt’s self-taught classical education, combined with a life experience that spans from the Civil War to the New Deal. To facilitate such an approach, Part Three: Teaching The Quary offers two venues. “The Quarry in Context” presents interactive exercises that reinforce close reading skills as students navigate to links related to the fictional and actual people, places, and things that populate the narrative. Finally, in keeping with the goal of viewing the novel in multiple contexts, “Teaching The Quarry in the 21 Century” offers study questions designed to examine the ways in which The Quarry can be read as a work that lays a foundation for African American multiculturalism, as well as the basis for the scholarly study of mixed-race literature, a new school of literary criticism that could not exist before the 21st century.