Chapter 2.0: Biological Models of Substance Misuse, Pharmacokinetics, and Psychopharmacology Principles

Ch. 2.1: Genetic Influences

Genetics explains about 50% of the risk for substance use disorders.

- A large body of evidence indicates that substance use disorder (SUD) can follow a familial pattern—but does not necessarily do so.

- Individuals with genetically close relatives (parents or adult siblings) experiencing a substance use disorder involving opioids, cocaine, cannabis or alcohol have up to an 8 times higher risk of developing a substance use disorder themselves (Merikangas, et al, 1998).

- Having a biological parent with alcohol use disorder increases the risk of developing problems with alcohol by about 4 times, even if raised by parents without a history of alcohol use disorder (Russell, 1990).

- Genetic studies paint a picture indicating that genetics are important in both the appearance of and resistance to substance use disorders.

- However, genetics alone do not determine a person’s destiny: genetic makeup interacts with the environment and a person’s lifetime of experiences to determine whether a substance use disorder emerges. The majority of individuals with genetic family histories of substance use disorders never develop the problem themselves.

Another fact that has emerged from decades of research is that there is no one specific “addiction gene” that applies to all of the different types of substances.

- Some of the genes involved are very specific to certain substances—what may “pull” someone toward an alcohol use disorder may not be “pulling” for a problem with cocaine, for example.

- Some genes are not specific to substance use disorders per se, but to a class of problems that have substance misuse as an element—for example, depression.

- The more we learn about specific combinations of genes that might be involved, exciting new biological tools for treating or even preventing addiction may emerge, including medications and perhaps even immunizations someday.

- For a basic background in understanding genetics, see the keywords list for DNA, alleles, genes, chromosomes, genome, genotype, heritability, and phenotype.

Four general lines of research contribute to our understanding of the role played by genetics in substance misuse and substance use disorder (SUD): family pedigree, twin, adoption, and genome studies.

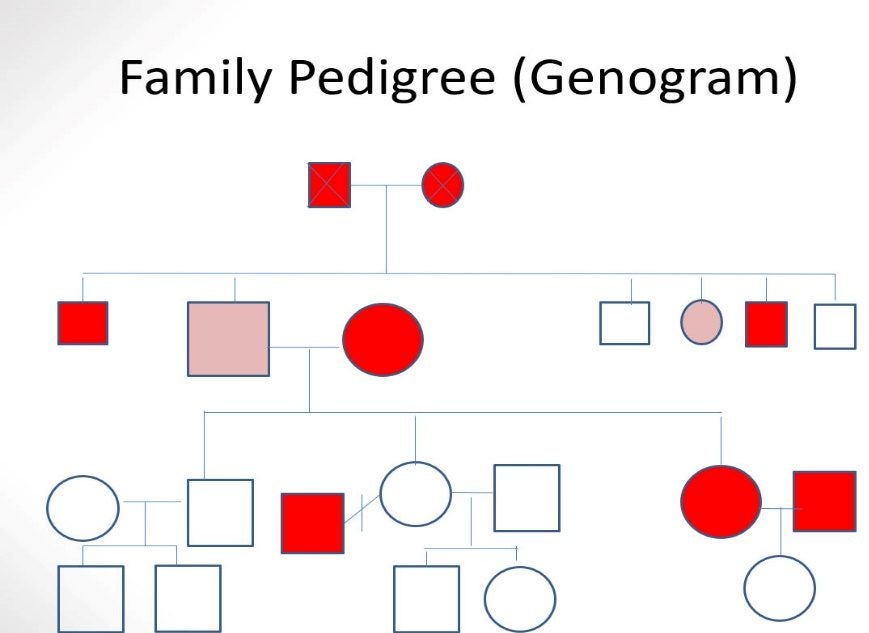

Family pedigree studies. Early genetic influence research relied on tracing the patterns with which a particular phenotype appears in multiple generations of a family—alcohol misuse and alcohol use disorder (AUD) is an example. These familial patterns become apparent when a pedigree chart is created (in social work practice, a family “genogram” is sometimes used in assessment; see Hartman, 1995). The observed pedigree patterns generally supported investigators’ hypothesis that the development of alcoholism has a genetic component—it is not entirely driven or dictated by genetics but is influenced by genetics. The more genetically close (proximal) in relationship, the greater the influence. For example, with alcohol use disorders, the influence of parents is stronger than the influence of aunts/uncles.

Figure 3-1 depicts a family’s pedigree for alcohol use disorder (dark red) and adults’ alcohol misuse (light red) for 3 generations—the youngest generation are still too young to know about. The common notation for a pedigree/genogram is that squares represent males, circles females, triangles unknown sex; lines between shapes represent couple relationships; lines above shapes represent offspring and sibling connections. An “X” through a symbol means the person is deceased and a crossed relationship line means the couple is no longer together.

Figure 3-1. Sample family pedigree (genogram) tracing alcohol use disorder.

Twin studies. Another source of evidence supporting the theory that alcoholism has a genetic basis comes from twin studies. There exist at least two types of twins, genetically speaking. Identical twins originate from the same single egg/sperm pair (monozygotic twins), thus they share the same genome. Fraternal twins, on the other hand, originate from two different egg/sperm pairings (dizygotic twins), thus they share a random amount of genetic coding, just as any sibling pairs might—on average, 50% is shared, but it could be anywhere along the range from almost 0% to almost 100%. The logic behind twin studies is to look at the degree of phenotypic similarity on some trait/condition, called “concordance,” between identical versus fraternal twins—if the degree of concordance is considerably greater among identical twins, this constitutes strong evidence for a genetic influence. In other words, it has moderate or high heritability. When the phenotypic outcome for identical twins is more than twice as similar as the outcome for fraternal twins, that trait is considered to be under a high degree of genetic control (Bares & Chartier, in press). Evidence for a genetic influence on alcohol use disorder is strong, but again—there also is sufficient lack of concordance between identical twins to show that it is not entirely driven by genetics.

Adoption studies. Adoption studies represent a third leg in the evidence base supporting a genetic influence on alcohol use disorders. These studies are based on comparing the phenotypic outcome of children raised by their biological parents with children raised by adoptive parents when the biological parent(s) exhibit the phenotype of interest. In this case, children whose biological parent(s) experience an alcohol use disorder who are raised by their biological parents or raised by adoptive parents who do not experience alcohol use disorder. Evidence suggests that among children whose biological father experienced an alcohol use disorder, being raised in an adoptive family was moderately but not entirely protective. In other words, there remains a considerable genetic influence (about 50-60%)–and, the child’s environment can confer a great degree of protection (Foroud, Edenberg, & Crabbe, 2010).

Genome studies. More recent lines of research go beyond answering the question “do genetics matter” to more specificity about “how genetics matters.” The human genome is a person’s complete set of DNA, represented in virtually every cell of the body. The Human Genome Project, completed in 2003, resulted in a generic “map” of the approximately 20,000-25,000 genes in the human genome (see the national Human Genome Research Institute’s genome.gov/about-genomics/fact-sheets/A-Brief-Guide-to-Genomics). This knowledge contributes greatly to understanding complex health problems (like substance use disorders) resulting from multiple genetic factors acting together and with the environment. Genome-wise association studies (GWAS) approached the study of substance misuse and SUD (and other phenotypic outcomes) in a unique manner: searching for common variants in allele frequency across the entire genome and then determining what phenotypic differences were associated with those variants (Bares & Chartier, in press). The GWAS approach is credited with identifying a genetic basis for phenotypes including heavy versus light amount of cigarette smoking or alcohol consumption, and developing nicotine or alcohol use disorder (Hancock, Markunas, Bierut, & Johnson, 2018).

Additionally, the Collaborative Studies on Genetics of Alcoholism (COGA) has established a database of information from over 10,000 individuals across multiple sites and over many years. The variables included measures of clinical, neuropsychological, electrophysiological, biochemical, and genetic factors, as well as individual and family histories of drinking behavior, from four groups of individuals (see http://pubs.niaaa.hih.gov/publications/arh26-3/214-218.htm):

- those meeting criteria for alcohol dependence (DSM-IV-TR criteria);

- those “at-risk” of alcohol dependence by virtue of their low level of response to alcohol—higher baseline tolerance, needing to consume greater amounts of alcohol than others in order to feel the effects is recognized as a vulnerability factor for developing alcohol use disorder;

- those meeting criteria for depression with or without alcohol dependence (two subgroups);

- “unaffected alcohol users” from families with one or more members experiencing alcohol dependence.

What Is Known About The Genetics of Substance Misuse

What has been learned from combining evidence from these four different types of studies includes the following:

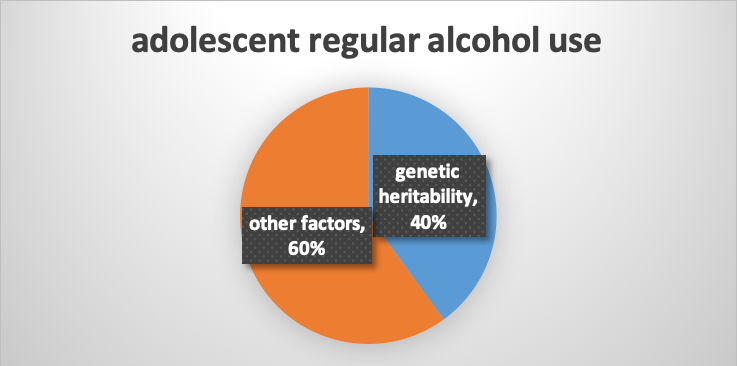

Genetics plays a significant role. As described in terms of the family pedigree, twin, and adoption studies, there is clearly a genetic influence on the development of alcohol use disorders. Less is known about other substances, however, there is convincing evidence from these and genomic studies that the probability of substance use becoming a substance use disorder (SUD) is influenced genetically (heritable) for many different substances. Not only is the emergence of SUD partially directed by genetics, but there appears to be a genetic contribution to the initiation and regular use of at least some substances, as well. For example, initiating tobacco use during adolescence was anywhere between 35%-80% heritable across different studies, regular tobacco use was between 40% to 50% heritable, and regular alcohol use was about 40% heritable (Bares & Chartier, in press). The evidence also demonstrates that it is not entirely driven by genetics—environmental factors play a significant role, as well (Bares & Chartier, in press).

Multiple genes involved. Evidence points to multiple genes contributing to substance use disorder (polygenic), even to a single type of substance use disorder (e.g., alcohol use disorder). Early genetic studies attempted to determine which specific gene or genes were candidates for playing a significant role in substance misuse behavior or SUD based primarily on their control of important, relevant biological processes; candidate gene studies generally showed inconsistent results, however (Bares & Chartier, in press). More recent approaches to understanding polygenic phenomena involve aggregating the many small effects each gene might contribute, resulting in a weighted total genetic effect (polygenic score, or PGS) taking into account the vulnerability and protective genes a person might have (Bares & Chartier, in press). In other words, we cannot point to any one gene as the “cause” of even a single type of SUD, much less SUDs in general.

Some genes may provide protection. At least one gene locus appears to provide protection from alcohol dependence, in contrast to gene sites contributing to vulnerability (Reich et al., 1998). Genes involved in controlling the processes of alcohol metabolism in the human body demonstrate a potential for preventing alcohol use from becoming an alcohol use disorder as exposure to alcohol creates a toxic, highly unpleasant physiological response (Edenberg, Gelernter & Agrawal, 2019). The protective allele (called ALDH2*2) is most common among individuals of Asian descent. Protective genes may exist for other substances, as well.

Severity is determined by specific chromosomal regions. Genetic influence is not simply occurring at the level of specific chromosome sites, but also in chromosomal regions (areas where multiple chromosomal sites cluster) and in various polygenetic combinations (multiple genes interacting). What this means is that a person may have various genetic forces pushing for and against developing substance misuse or SUD problems in a kind of genetic tug-of-war. As a result, we see a wide range of phenotypic expression in the population as a whole—the problem is heterogeneous, not “one size fits all.”

Common versus specific origins. Analysis of a vast body of science provided answers to the question of whether SUD involving different types of substances has a shared, common genetic origin or whether each type of substance has its own unique genetic influences (Li et al., 2011). The answer is not simple: some genomic areas appear to be shared across different types, while other areas are substance-specific (Begun & Brown, 2014). There does appear to be some shared commonality in genetic vulnerability to nicotine, alcohol, and cannabis dependence, at least among men. The underlying common genetic factors, however, fail to explain the high degree of variability in phenotypic expression (Palmer et al., 2012). There exist specific genetic factors, as well, also operating at the same time, including specificity for alcohol, tobacco, marijuana, and cocaine (Palmer et al, 2012). One common underlying genetic factor may be the presence of genetics linked to depression—for some individuals, depression and SUD have common genetic influences, but this is not true for everyone with either/both experiences.

SUD heritability was stronger among men. While heritability of alcohol use disorder was observed for both men and women, the case appeared to be stronger among men. In other words, environmental factors explained a greater proportion of alcohol use disorder among women (Kendler et al., 1992; Jang, Livesly, & Vernon, 1997). However, this gender-based differentiation is less noticeable in recent cohorts than historically, at least for alcohol or nicotine dependence (Palmer et al., 2012).

Summary

In answer to the “Is it genetic?” question about substance use disorder, the evidence from multiple sources indicates “sort of.” The situation is complex. Some aspects of substance use, substance misuse, and substance use disorder are influenced by genetic forces, but there is a great deal about each of these behaviors/experiences that is influenced by other than genetic forces, too. Furthermore, the genetic forces do not all push in the same direction or to the same extent—some forces push for and other against the problems emerging. We also know that SUD is not a single phenomenon—susceptibility differs for different substances. For example, a propensity toward alcohol use disorder may or may not align with propensity for nicotine or cocaine use disorder. And, the genetic forces related to certain co-occurring problems may also relate to the propensity for developing a specific type of SUD.

Stop and Think

Your Family Pedigree

Sketch a diagram of your family’s genogram for at least three or four generations, as much as you know about. This could be your biological or adoptive family “tree.” Use color to highlight everyone you know/suspect had a certain characteristic of interest to you (e.g., nicotine dependence, alcohol use disorder, diabetes, heart disease/stroke) during their lifetime. Is there any pattern to what you see? What are the implications for your own vulnerability? What are the implications for your own resilience? Do you see how genetics are informative but not completely predictive of what happens?