Chapter 4.0: Psychological Models of Substance Misuse

Ch. 4.2: Developmental Theories

In recent years, a great deal of research, clinical, policy, and prevention attention has been directed to substance use among young adolescents, adolescents, and emerging adults. Not only do we care about the well-being of these young people in the here and now, while they are young, but because it has profound implications for their future lives, as well. This brings us to look at developmental theories of substance use and addiction.

Relatively recently, scholars have begun to argue for viewing substance use disorder within a developmental framework. Strong arguments are made for considering “the role of genetic, epigenetic, and neurobiological factors alongside experiences of adversity at key stages of development” in approaching the topic of addiction (McCrory & Mayes, 2015). This argument is informed, to a large extent, by evidence concerning the significant role played by adverse childhood events (ACEs) in the emergence of substance use, misuse, and use disorders—exposure to child neglect, child maltreatment, and substance misuse by parents/caregivers (McCrory & Mayes, 2015). For instance, adults who had experienced court-documented child victimization (physical abuse, sexual abuse, neglect) were about 1.5 times more likely to report using illicit substances (especially marijuana), using more types of illicit substances, and experiencing more substance use-related problems compared to adults without this childhood history (Widom, Marmorstein, & White, 2006). In another study, severity of self-reported exposure to childhood physical, sexual, and emotional abuse and other traumas were positively correlated with lifetime drug and alcohol use and this relationship was related to the individuals’ level of emotional dysregulation (Mandavia, et al., 2016). Regardless of the root causes, it is important to consider developmental processes in substance misuse.

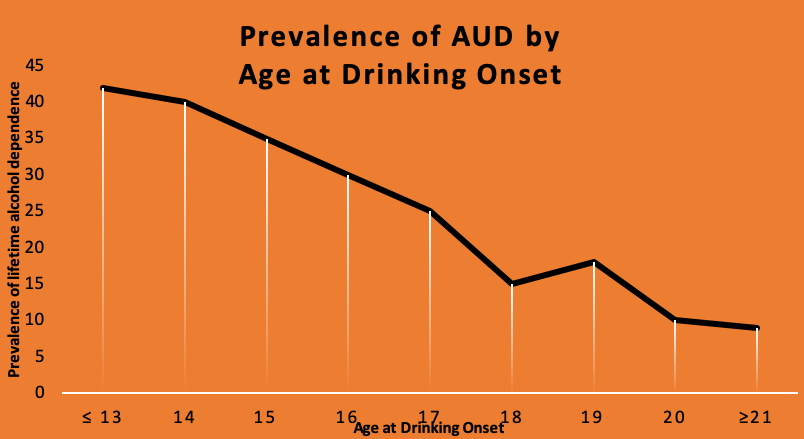

Developmental trends data. The following graph displays data from the 2001-2002 National Epidemiologic Survey on Alcohol and Related Conditions (NESARC). The data demonstrate a trend in which the younger a person is when beginning to drinking alcohol, the greater the likelihood of developing an alcohol use disorder at some point during that person’s lifetime. The greatest prevalence of alcohol dependence appeared among individuals who began drinking at or before age 13; the lowest prevalence of alcohol dependence appeared among individuals whose drinking began at or after age 21. Individuals who begin drinking before the age of 15 years are four times more likely to someday develop alcohol dependence than individuals who did not drink before the age of 21 years. For each year of age that the onset of drinking is delayed, the odds of developing alcohol dependence sometime in life decreases by 14%. This is a pretty important argument for prevention efforts that can help delay drinking onset! This also suggests that something important may be happening developmentally.

Some of the impact is due to changes in the developing brain that occur with exposure to alcohol during the adolescent and emerging adulthood years—this is a period of very rapid brain reorganization under normal developmental conditions so exposure to alcohol during this time may affect the brain more dramatically than alcohol exposure later in brain development. The adolescent brain is more sensitive to the rewarding/reinforcing experience of alcohol exposure than would be true if first exposure occurred later in life.

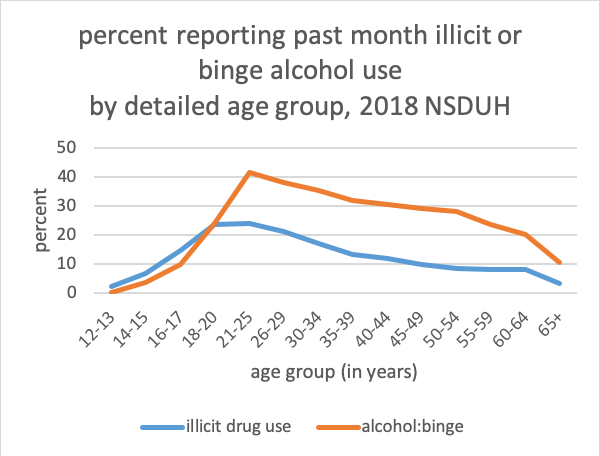

Consider also that substance use patterns are not consistent or linear in their changes with age, either. Data from the 2018 NSDUH study showed marked differences in substance use by young adults (aged 18-25) compared to younger and older individuals. With most substances, the numbers of individuals engaging in use or misuse increase from early adolescence through adolescence and emerging adulthood, then begin to decline again throughout most of the remaining adulthood period. Here is a graph created using the 2018 NSDUH data for past month illicit drug use by detailed age category:

Because these data are cross-sectional rather than longitudinal, we do not know if the use patterns for each individual followed this type of pattern, only that this pattern reflects the use at one point in time for the different groups. While it suggests a developmental trend, it does not confirm that such exists. For example, it is possible that the declining numbers may be at least partially attributable to attrition—individuals engaging in these behaviors over time may be less likely to survive to represent the later age groups.

Developmental trends in behavioral control. However, if the increasing rates during adolescence and early/emerging adulthood are reflective of a developmental trend, it is possible that the principle of behavioral under-control may be relevant. Adolescent brains undergo dramatic developmental changes and functional revisions as part of normal development. The synaptic and myelination revisions do not occur evenly and concurrently throughout the brain. For example, the areas responsible for inhibitory control over behavior do not keep up with the same pace of change as areas responsible for initiating behavior. This explains why adolescents might behave more impulsively, exhibiting less inhibitory control over their behavioral choices—what might appear to be “poor judgment” at times. In other words, adolescents make under-controlled choices at a higher rate than they might have at a younger age or than they will at an older age (assuming that their choices do not prevent their achieving older ages). Thus, it is not surprising that we might see rates of under-controlled drinking behavior rising in this age group compared to other age groups. As the brain continues to mature, and behavioral control (inhibitory) areas catch up to behavior initiation areas, we may expect to see greater behavioral control (inhibition) exhibited. This concept of behavioral under-control as a developmental phenomenon could apply to substance use, aggression, and risk-taking behaviors in general.

Developmental trajectories of substance use disorder. During the 1950s and 1960s E. Morton Jellinek concluded that alcoholism follows a natural course over time, a course characterized by four qualitatively distinct stages: pre-alcoholic, early alcoholic, middle alcoholic, and late alcoholic (Jellinek, 1952). Despite many years of influence, Jellinek’s developmental model has been criticized for being based on a small, select sample (of men in Alcoholic Anonymous programs), and because progressive worsening of symptoms is not universal (see (see Begun, in press): a great deal of clinical heterogeneity exists (Moss, Chen, & Yi, 2007). More recent studies demonstrated the dynamic, constantly changing nature of addictive behaviors: “Addiction can be viewed as a trajectory that emerges, becomes ingrained, and then in most cases evolves further (people quit or learn to control their use) over time” (Heather et al., 2018, p. 251). Yakhnich and Michael (2016) described the trajectory as a process beginning with occasional use of substances and ending with addiction, recognizing that many individuals “mature out” of excessive use at points along the trajectory.

A three-stage cycle of addiction related to the brain-behavior circuit has been offered as a model to consider (Koob & Volkow, 2010; White & Koob, in press). The first stage concerns substance use that progresses to binge and/or intoxication. This stage involves the acute reinforcing nature of psychoactive substances on reward systems of the brain. The second stage is called the withdrawal/negative affect stage. As the brain adapts to chronic substance exposure, withdrawal of the substances leaves a person fatigued and experiencing decreased mood, anxiety, stress-related symptoms, and possibly decreased motivation to earn natural rewards. The third stage in this model is a preoccupation/anticipation and craving stage. In this stage, “the individual reinstates drug-seeking behavior after abstinence” (Koob & Volkow, 2010, p. 225). Stress stimuli may heighten the effect. The three-stage model is used to explain what happens when individuals progress to a state of addiction. Not everyone progresses through these stages, however, just as not everyone progresses from substance use to substance use disorder.

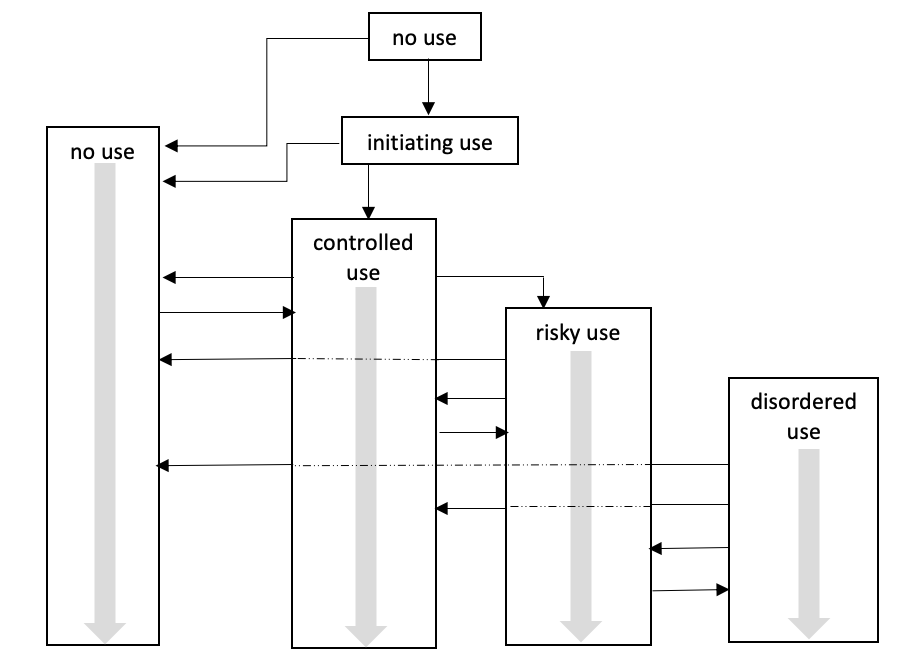

A 60-year longitudinal study of college-aged men whose drinking patterns were identified as “alcoholism” demonstrated widely varied patterns in later adulthood, including stable abstinence, non-problematic/controlled drinking, alcohol abuse, or death (Vaillant, 2003). A typical substance misuse trajectory begins during adolescence or emerging adulthood, declines or escalates during emerging and early adulthood—where it may or may not meet criteria for a substance use disorder—then either declines or extends into adulthood, possibly but not necessarily meeting criteria as a substance use disorder (see figure below, from Begun, in press).

Important aspects of this figure are the multiple pathways/trajectories that occur and the iterative nature of the possible trajectories: for example, moving back and forth between controlled, risky, disordered drinking, and no alcohol use. The probability of different trajectories is affected by a host of individual-specific factors, as well as the “addictive potential” of different substances involved (Upah, Jacob, & Price, 2015) and individuals’ different histories of change attempts over the life course (Begun, Berger, & Salm-Ward, 2011). Similarly, no single, “natural” trajectory to/through recovery exists and there are a multitude of addiction “careers” in individuals’ relationships or involvement with substances over their lifetimes following the emergence of a substance use disorder (DiClemente, 2006).

Multiple factors play a role in “positive outcome” trajectories, including engaging in treatment—but treatment is not a requirement. For example, U.S. combat veterans who experienced both posttraumatic stress disorder and hazardous drinking behavior were less likely to continue hazardous drinking if they had engaged in alcohol-specific treatment, despite persistent/unremitting PTSD symptoms, and particularly if their drinking had led to negative consequences (Possemato et al., 2017). But the field also recognizes “natural” recovery as a studied phenomenon whereby many individuals change their problematic alcohol or other substance use without engaging with formal treatment systems (DiClemente, 2006; Sobell, Ellingstad, & Sobell, 2000), or by combining formal, informal, and natural recovery systems in their change efforts (Begun, Berger, & Salm-Ward, 2011). Surprisingly, this even included a cohort of veterans returning from Viet Nam with heroin use disorders (Robins, 1993).