Chapter 4.0: Psychological Models of Substance Misuse

Ch. 4.4: Expectancies and Cravings

As a part of the cognitive framework concerning the initiation of substance use/misuse, we can look at the kinds of expectancies individuals might hold concerning the likely outcomes or effects associated with substance use—what using alcohol or other drugs will do to or for them. To understand continued use of substances over time, particularly when someone experiences the urge to use substances despite consciously not wanting to do so, it is important to look at the psychological phenomenon of cravings.

Expectancies

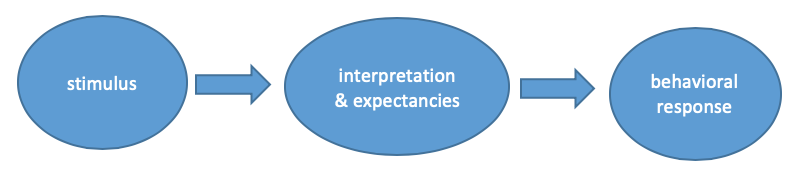

Expectancies act as a filter in the appraisals individuals make when faced with a substance use opportunity (stimulus) and their behavioral response. An expectancies process diagram is very similar to what we saw in relation to the cognitive behavioral process; the major difference being that expectancies become part of the interpretation step. What a person has come to expect as the likely outcomes of the behavior becomes part of the interpretation.

Children develop expectancies about alcohol at a very early age—even preschool/kindergarten aged children may already have developed ideas about the emotional effects of adults’ drinking (Kuntsche & Kuntsche, 2018). One source of their expectancies was parental drinking: sons identified positive emotional consequences (e.g., feeling happy, calm, relaxed) if a parent engaged in moderate drinking and they identified negative emotional consequences (e.g., feeling angry, sad, depressed) if a parent engaged in heavy drinking; the effects were less consistent among daughters and were stronger when the parent was the father rather than the mother (Kuntsche & Kuntsche, 2018).

You may find it interesting to see what 8th, 10th, and 12th graders in the U.S. hold as expectancies concerning different substances—and that these expectancies relate to substance use behavior. These data were generated in the annual Monitoring the Future study during 2018 and ask in relation to various substance-related behaviors, “How much do you think people risk harming themselves (physically or in other ways), if they…”; presented here are the percentages responding with “great risk” (https://www.src.isr.umich.edu/projects/monitoring-the-future-drug-use-and-lifestyles-of-american-youth-mtf/).

|

Behavior |

8th grade |

10th grade |

12th grade |

|

try marijuana once or twice |

20.3 |

13.9 |

12.1 |

|

smoke marijuana occasionally |

32.1 |

21.4 |

14.3 |

|

smoke marijuana regularly |

52.9 |

38.1 |

26.7 |

|

try inhalants once or twice |

29.6 |

38.6 |

— |

|

take inhalants regularly |

46.8 |

57.6 |

— |

|

take LSD once or twice |

20.8 |

33.8 |

29.0 |

|

take LSD regularly |

36.4 |

54.1 |

55.2 |

|

try cocaine powder once or twice |

42.6 |

52.6 |

47.9 |

|

take cocaine powder occasionally |

61.0 |

70.2 |

62.1 |

|

try heroin once or twice (without using a needle) |

59.5 |

71.4 |

63.1 |

|

take heroin occasionally (without using a needle) |

72.1 |

81.0 |

69.6 |

|

try one or two drinks of an alcohol beverage (beer, wine, liquor) |

13.6 |

13.0 |

10.2 |

|

take one or two drinks nearly every day |

28.7 |

30.3 |

22.8 |

|

have five of more drinks once or twice each weekend |

52.3 |

51.8 |

59.1 |

|

smoke one to five cigarettes per day |

40.8 |

49.9 |

— |

|

smoke one or more packs of cigarettes per day |

61.3 |

69.6 |

73.9 |

|

vape an e-liquid with nicotine occasionally |

16.9 |

17.9 |

15.8 |

|

vape an e-liquid with nicotine regularly |

32.4 |

31.3 |

27.7 |

Expectancies, at least those related to alcohol use, do not remain consistent over time. During early adolescence, negative alcohol expectancies tend to diminish while positive expectancies tend to increase (Smit et al., 2018), and positive alcohol expectancies tend to become more stable with progressing age (Wardell & Read, 2013). This is important because alcohol expectancies are predictive of alcohol use initiation, as well as drinking behavior over time (Smit et al., 2018). Among college students, those who held strong positive expectancies about binge drinking (sociability and sexuality) were more likely to engage in binge drinking than students whose positive expectancies endorsement was weaker (McBride et al., 2014).

Besides parental substance use, where do alcohol and other substance use expectancies come from? In some cases, expectancies come from a person’s own direct experiences. In others, expectancies emerge from observational learning. Observational learning, especially among children, involves fictional as well as real-world models. For example, consider the scene in the original cartoon Disney movie Dumbo where the little elephant gets a big drink of liquor and sees dancing pink elephants on parade. An expectancy might be that alcohol makes you see the world in interesting new ways, or it may seem scary and creepy, depending on the emotions prompted by viewing this scene.

From what individuals see in their homes, neighborhoods, schools and jobs, media, and social media they develop expectancies about alcohol, drugs, sex, smoking, gambling, and many other types of behavior. These expectancies may influence how situations are appraised and interpreted, which in turn influences choices and behavioral responses. If the expectancy is that using a particular substance will make you feel good/better, substance use is likely to be appraised as a good solution to a bad day, a bad break up, or receiving bad news. If the expectancy is that using these substances will just delay the day of reckoning, and maybe let the problem get worse with time, or that it will make you feel low and depressed, then substance use is likely to be appraised as a bad idea.

Cravings

As previously discussed, internal and environmental cues can become craving triggers through classical conditioning processes, with exposure to those triggering cues increasing the risk of using substances again. This is called a cue-induced response. Cues or “triggers” may involve any combination of the five senses (sight, sound, taste, feel, and smell) or internal states (e.g., anxiety, loneliness, boredom, depression, mania). For example, one woman in treatment for a substance use disorder described loud rock music as a personal trigger for her craving to use alcohol and marijuana because she “learned” to enjoy these substances at rock concerts. Regardless of its nature, craving cues trigger “abnormally strong desires to engage in addictive behaviours,” though not necessarily leading to subsequent use (Heather, 2017, p. 32). One skill addressed in cognitive-based therapies is for individuals to learn to identify their own personal triggers or cues and develop strategies to (1) avoid potentially triggering situations, and (2) respond differently to them when they cannot be avoided. For example, someone might rehearse a series of coping skills, such as relaxation or mindfulness practices, to employ when cravings occur, as a means of interrupting the “old” behavioral response (called coping skills training, or CST). Cue-exposure treatment is a type of behavioral therapy that involves systematic desensitization to learned cues as a means of reducing the degree to which someone reacts to the triggering stimuli/cues (Monti & Rohsenow, 1999). While this alone may not be sufficient for someone to break the cue-induced response, and the intervention must be delivered very carefully in order not to actually trigger a relapse, this kind of intervention may help decrease an individual’s response to the cues to the point where they can focus on applying their other coping skills.

Stop and Think

Think about your personal attitude about getting drunk on alcohol or high on cannabis. What factors in your past and present environment, experiences, and observations contributed to your favorable, unfavorable, and ambivalent attitudes?

Think about the environments and experiences that you have in a typical day. What among them might create an experience of craving for a person in recovery from alcohol or other substance misuse/use disorder? How might a person avoid these kinds of trigger events?