Chapter 5.0: Social Context and Physical Environment Models of Substance Misuse

Ch. 5.1: Social Contexts and Physical Environments

This chapter presents a general overview of theories/models concerning the role of social contexts and physical environments in substance misuse and opportunities for prevention or treatment. These are often referred to as sociocultural theories, but that label does not provide sufficient emphasis about the role of physical environments. Here we are concerned with social systems and social structures, physical environments, social norms, culture and subculture, and the impact of “isms” and labeling theory. Evidence points to many relevant social and environmental factors that play a role, such as:

- Stigma

- Policy and global forces

- Family and family system dynamics

- Peer groups

- School and workplace

- Neighborhood and community

Stigma

Social stigma refers to negative social attitudes or stereotypes about a type of person or behavior (Begun, Bares, & Chartier, in press). Stigma about persons who engage in substance use or substance misuse, experience a substance use disorder, seek treatment for substance-related problems, or are in recovery has an impact on their opportunities and experiences. The stigma could stem from their own beliefs about what they are doing, attitudes expressed by individuals in their immediate social contexts, attitudes encountered in their interactions with professionals, and/or attitudes and opportunities (or lack of opportunities) expressed through policies. Stigma affects a person’s willingness to engage in treatment, which then can translate into further marginalization, blame, and increased barriers to seeking help for substance misuse and related problems (Kulesza et al., 2016). “Explicit bias refers to the beliefs, attitudes, and social norms of which someone is conscious and aware, whereas implicit bias reflects those lying outside of conscious awareness and intentional control; explicit and implicit bias may not fully align even within the same person’s belief systems” (Begun, Bares, & Chartier, in press). For example, explicitly expressing a belief that someone engaged in injection substance misuse is more deserving of treatment help than punishment as a criminal might not be consistent with what is held as a belief at the implicit level (Kulescza et al., 2016).

Persons experiencing substance use disorders regularly encounter stigma that profoundly impacts their everyday lives (Fraser et al., 2017). For example, they may encounter stigmatized attitudes when they seek health care—either being “blamed” for health conditions related to their substance use or “accused” of deceptively seeking drugs from the healthcare system. Stigma often informs policy at the organizational, local, state, federal, and international levels, as well. Comparing vignettes of successfully treated and untreated addiction led to the conclusion that, since portraying successful treatment was followed by a greater belief in the effectiveness of treatment and less willingness to discriminate against persons experiencing drug addiction, stigma could be reduced through media campaigns and public education (McGinty, Goldman, Pescosolido, & Barry, 2015)—messages along the lines of SAMHSA’s message: “prevention works, treatment is effective, and people recover from mental and/or substance use disorders” (https://www.samhsa.gov/find-help/recovery).

Policy as a Context Influence

Social, public, and health policy are tools for influencing outcomes by manipulating the social and physical contexts in which individuals live, develop, and function (Begun, Bares, & Chartier, in press). For example, state and federal policies that increased the legal drinking age (Wagenaar & Toomey, 2002), specified the age for legally obtaining tobacco products (Schneider et al., 2016), and established a uniform blood alcohol level (BAL, or blood alcohol concentration, BAC) for intoxicated operation of a motor vehicle are social control actions to influence substance use behavior at the individual level. Lack of social control is also a factor: when first introduced, electronic cigarettes (e-cigarettes, vaping) were not regulated as tobacco products, allowing legal access and use by adolescents who could not legally purchase combustible cigarettes (Cobb, Byron, Abrams, & Shields, 2010). Adolescent e-cigarette use was subsequently related to higher rates of tobacco use (Wills et al., 2017).

Policy restrictions related to advertising of psychoactive substances such as alcohol, tobacco, vaping products, and cannabis/marijuana potentially affect the physical environments in which individuals make choices about substance use. For example, where tobacco advertising appeared in greater numbers, use by young people too young to legally purchase these products nevertheless was increased (Kirchner et al., 2015). Policy can influence substance use patterns through affordability mediated by taxation. Use of tobacco products has a demonstrated relationship to states’ taxation rates (Luke, Stamatakis, & Brownson, 2000); alcohol use has similarly been shown to be tax-rate sensitive. Use of tobacco is also related to the density of retail outlets that sell tobacco; density is highly sensitive to local and state policy (Cantrell et al., 2015; Novak, Reardon, Raudenbush, & Buka, 2006).

Physical Environments

An obvious physical environment aspect important to consider has to do with a person’s access to alcohol or other drugs. In general, the physical environment produces opportunities and obstacles that shape the behavior of people living in those spaces and places. For example, the nutritional value of a person’s diet is influenced by living in a “food desert” or other conditions of food insecurity versus where healthful foods are easily accessed and affordable. Specific to substance use, consider how difficult or easy it is for someone to gain access to alcohol, tobacco, or other substances in the family home, school, workplace, peer group, or neighborhood. One set of questions tracked over time in the U.S. national survey of middle and high school students called Monitoring the Future (Miech et al, 2018) concerns how easy or difficult students believe it is to obtain various substances. As you can see from Table 1, belief in easy access to each of the different substances increased from 8th to 10th to 12th grade.

Table 1. Percent of students responding “fairly” or “very” easy to obtain substances, created from Monitoring the Future data 2018, retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/data/data.html

| substance | 8th graders | 10th graders | 12th graders |

| alcohol | 53.9 | 70.6 | 85.5 |

| cigarettes | 45.7 | 61.5 | 75.1 |

| marijuana | 35.0 | 64.5 | 79.7 |

| vaping device | 45.7 | 66.6 | 80.5 |

| e-liquid nicotine | 37.9 | 60.4 | 77.2 |

| LSD | 6.5 | 14.9 | 28.0 |

| heroin | 7.8 | 9.7 | 18.4 |

| other narcotics | 8.3 | 16.8 | 32.5 |

| cocaine | 9.8 | 14.7 | 23.0 |

| steroids | 10.9 | 14.5 | 21.1 |

Access to substances is not the only mechanism through which the physical environment influences substance use and misuse at the individual level. Investigators secondarily analyzing data from large-scale surveys concluded that living in a neighborhood with more opportunities for adolescents to engage in substance use had several effects (Zimmerman & Farrell, 2017):

- detrimental effects of parental substance use/misuse were amplified in the youths’ risk;

- detrimental effects of peers’ substance use were amplified in the youths’ risk;

- protective effects of the youths’ perceptions of harmfulness from substance use were diminished.

Additionally, the physical and social settings where substance use occurs have an impact on substance use behavior. Among college students, drinking setting was observed to make a difference in drinking behavior (Clapp et al., 2006). Many other patrons or party-goers being intoxicated, drinking games, and illicit substances being present in either public or private drinking settings (versus private parties) were associated with higher alcohol consumption by individuals attending those settings. Sexual assault by intoxicated persons is also related to drinking setting with “bar culture” being a significant contributor (Davis, Kirwan, Neilson, & Stappenbeck, in press).

Consider also the harm reduction practice of providing supervised injection sites/facilities: locations provided in several European countries and Canada suggest that these locations, as opposed to other public or private spaces, reduce needle sharing, promote safer drug use, encourage access to services and entry into treatment, and make available staff to respond in the event of an overdose (https://harmreduction.org/blog/sif_dcr/). In other words, setting can make a difference in behavior.

Gene-Environment Interplay

Social and physical environment elements have a great deal of power to potentially modify genetic and psychological influences on health-related outcomes, including substance use initiation, substance misuse, and the development of substance use disorders (Begun, Bares & Chartier, in press). For instance, social and physical environment factors may compound vulnerabilities or impart resilience by either imposing constraints or offering opportunities that enable, trigger, disrupt, or strengthen biological or psychological effects (Bares & Chartier, in press). Evidence supports the notion that genetic predisposition to alcohol use/misuse/use disorder and environmental exposures interact to influence alcohol use patterns (Sher et al., 2010). Similarly, this type of interaction was observed in tobacco use patterns (Chen et al., 2009). The concept of a gene-by-environment interaction indicates that a person’s genetic makeup can determine sensitivity to environmental effects and whether environmental exposure enhances or diminishes genetic effects (Bares & Chartier, in press). A body of research concerning alcohol, cigarette, and other substance use initiation, as well as for regular substance use, generally suggests that the influence of environment is stronger during early adolescence and gradually shifts to genetic factors (heritability) playing a more predominant role in adult development (Bares & Chartier, in press). For example, parental monitoring can reduce the influence of genetic heritability in cigarette use (Dick et al., 2007). Additionally, genetic effects on alcohol use are more evident among adolescents receiving low levels of parental monitoring, as well as adolescent affiliating with peers who engage in high levels of deviant behavior (Kendler, Gardner, & Dick, 2011). There exists an interaction between intrinsic (biological and psychological makeup) and extrinsic environmental forces related to substance misuse. Biological, psychological, and social context models are integrated into a unified bio-psycho-social-spiritual framework.

Social Systems

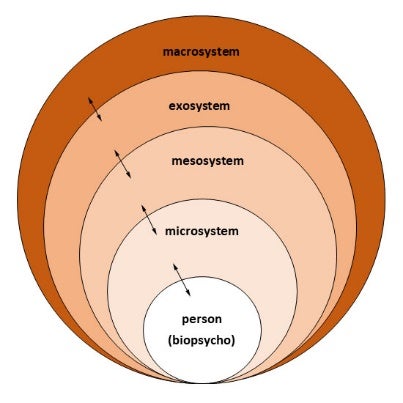

Anthropologists argue that the use of substances can only be properly understood when placed within a social context: the family, social, school, work, economic, political and religious systems (Hunt & Barker, 2001). The social ecological model (Bronfenbrenner, 1986, 1996) related to human development occurring within social systems at varying levels helps direct attention to social contexts as related to substance misuse—as well as informing interventions for substance misuse prevention and recovery support.

Social Ecological Model. In considering how a social ecological model might apply to substance misuse, we can start with the heart of the matter: the center of the model represents the individual person. This sphere incorporates what we have studied so far in relation to a person’s biological and psychological makeup—the bio and psycho components. This is what the person brings to any interactions or experiences with their social or physical environments. Next, we look at the many contextual spheres of influence, forming an appreciation for an individual’s social ecology. These begin at the most intimate, daily connections through a series of progressively more remote spheres of influence: the micro-, meso-, exo-, and macro- system levels (see Figure 1). These social systems influence individuals, individuals influence them, and they influence each other. These multi-directional influences explain why there are arrows between system levels depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Diagram representing social ecological model’s multiple system levels

Microsystem influences include social systems with which individuals directly interact on a regular basis: immediate family members/partners, close friends, and others in the most personal, intimate sphere of daily living. These microsystem members have a powerful effect on an individual’s behavior through various mechanisms, including the way that they influence learning through delivering consequences (reinforcing or punishing) behaviors, serving as the models for behavior (social learning theory), communicating expectations (expectancies and social norms), and possibly triggering cravings. These microsystem members also influence the immediate physical environments. For example, they may make it easier to access alcohol, tobacco, or other drugs. While the microsystem influences an individual’s experiences and environments, the individual influences the microsystem, as well. Consider how a person’s substance use affects their own behavior and responses to family members or friends; influences on parenting, relating to an intimate partner, or engaging with friends might be affected, along with the effects of bringing illegal activities into the relationship or home environment. This, in turn, has a reciprocal influence on the social context and physical environment experienced by the family and friends in the microsystem. The microsystem of recovery might include one’s sponsor in a mutual aid/peer support/12-step type of program.

Moving one sphere further out, the microsystem influences and is influenced by the mesosystem. The mesosystem components include elements in the relatively immediate environment with which an individual routinely interacts, but less frequently and intimately than was true of the microsystem. For some individuals this includes extended family members and peers/friends with whom the relationships are influential but not as close and intimate. It might include the companions in the workplace or at school, and it might include neighbors. For some individuals this might include members of a religious or spiritual community. The mesosystem of recovery might include companions in the peer support community, other members of mutual aid/peer support/12-step type programs. It is also possible that members of the formal health/mental health/addiction treatment system fit into the mesosystem context.

The exosystem is one more step removed in terms of regular interactions and direct impact. This includes social institutions with which a person directly engages, but somewhat less frequently and intimately. Depending on the nature of the interactions, social institutions designed to provide services might be in the mesosystem for a particular person or family. For example, this might distinguish between the office where someone works (mesosystem) and the company for whom the person works (exosystem). Or, it might distinguish between the person providing recovery treatment (mesosystem) and the agency where treatment is being provided (exosystem). The practices and policies of these social institutions (e.g., zero tolerance policies) influence the individual’s experience in the social environment through indirect interactions, often filtered through intervening systems (mesosystem and microsystem). A significant component of the exosystem involves community policing around substance-related activities. For individuals involved with drug court by virtue of their substance-related activities, the team of professionals might be part of the mesosystem and the social service delivery systems as part of the exosystem.

Finally, we have the macrosystem to consider. While few of individuals directly interact on a routine basis with the elements shaping the cultures and societies in which they live, these elements exert powerful (though indirect) influences on experience. Consider, for example, how changes in the legal status of certain substances influences behavior at the individual level. Popular social media platforms provide an interface between what happens at the macrosystem (and exosystem) level and the more intimate levels of our social environments. It helps shape attitudes, values, beliefs, stereotypes, and stigma about substance use that are then expressed in the mesosystem and microsystem. Social workers and other professionals cannot afford to ignore the impact of policy, laws, and law enforcement patterns operating at exosystem and macrosystem levels on the social context of substance use at more proximal levels. For example, in many communities there exists a reciprocal relationship between the two problems of heroin use and the abuse of prescription pain medicines: as communities crack down on prescription drug abuse, making the substances more difficult to obtain, problems with heroin seem to explode.

Within this social ecological framework, we can look more closely at theories concerning the mechanisms by which these social ecology elements have their impact, and at evidence concerning these different elements.

Circularity of Influence. As noted in the previous discussion, but warranting an emphasis and attention is that individuals being influenced by the social and physical environments is one part of the equation: it is also true that they have an influence on their social and physical environments, as well. Anyone who has cared about a friend or family member experiencing substance use disorder will tell you that the individual’s substance use, related behaviors, and consequential problems not only affect that individual but also has an impact on those in the social and physical contexts, as well. The individual’s behaviors affect many different types and levels of social and physical environments; the very environments that influence that individual, too. This iterative pattern of influence continues over time—the environment influences the person who influences the environment, and the changed environment continues to influence the changed person, and so on over time. This is what is meant by the concept of circularity of influence. This perspective acknowledges that individuals are actively engaged with their environments, not simply the passive recipients of environmental influences; furthermore, individuals make choices and decisions from among options available in their social and physical contexts, choices that have consequences for themselves and others in their social/physical contexts, as well (Begun, Bares, & Chartier, in press; Shelton, 2019).

Social Norms

A culture’s or group’s collective expectations about acceptable behavior are represented in its social norms. Social norms are key social processes related to many types of behavior, including substance use and misuse. Groups may have specific norms about initiating substance use, acceptable patterns for regular use, excessive use or intoxication, seeking treatment for substance-related problems or substance use disorder, and recovery support. For example, most cultures accepting of alcohol use have norms related to the boundaries of its acceptable use—when, where, by whom, and how much. Social norms influence individuals’ behavior choices. For example, a person who believes that “everyone else” either uses or approves of using cannabis is far more likely to engage in its use than a person who believes that it is not common or accepted in their social context. Or, for example, social norms against driving under the influence of alcohol (or other substances) influence the behavior of individuals electing to use sober driver strategies when planning to participate in drinking events. On the other hand, if public education efforts deliver messages that “too many young people” use alcohol, tobacco, or vaping products, the actual message received by that population may be that engaging in this behavior is normative and accepted within their group. In other words, the message could backfire as a preventive strategy because it actually conveys a positive social norm about the behavior. Social norms surrounding substance use are significantly related to substance use behavior, especially among adolescents (Eisenberg et al., 2014). Media campaigns have proven effective in shaping norms and health-related behaviors related to intoxicated driving, use of tobacco products, and parents discussing substance misuse with their children (Wakefield, Loken, & Hornik, 2010). See, for example, the “Don’t Live in Denial Ohio” media campaign (https://dontliveindenial.org/).

To understand young cohorts and their norms related to substance use, consider Monitoring the Future 2018 study results (Table 2). The survey asked students to rate their own level of disapproval toward people who use various substances. What is interesting in these data is that the trend is substance-dependent. Between 8th, 10th, and 12th grade each group of students was more accepting of alcohol and marijuana use than the next younger group. The opposite was true of heroin, cocaine, LSD, inhalants, and regular vaping of e-liquids containing nicotine. It is not clear whether these cross-sectional data reflect a true developmental change in youths’ opinions. However, it does suggest that as the students progressed in age/grade, they make clearer distinctions between types of substance use.

Table 2. Percent of students who disapprove or strongly disapprove of “people who …”, created from Monitoring the Future data 2018, retrieved from http://www.monitoringthefuture.org/data/data.html

| Do you disapprove of people who… | 8th graders | 10th graders | 12th graders |

| try one or two drinks of an alcoholic beverage | 47.4 | 39.6 | 31.3 |

| take one or two drinks nearly every day | 77.9 | 77.9 | 74.7 |

| have five or more drinks once or twice each weekend | 83.7 | 80.4 | 75.8 |

| taking 4 or 5 drinks nearly every day | — | — | 91.7 |

| try marijuana once or twice | 64.5 | 47.9 | 41.1 |

| smoke marijuana occasionally | 73.1 | 57.4 | 49.2 |

| smoke marijuana regularly | 79.3 | 69.7 | 66.7 |

| try heroin once or twice without using a needle | 85.5 | 90.6 | 93.0 |

| take heroin occasionally without using a needle | 86.8 | 91.2 | 93.4 |

| taking heroin regularly | — | — | 96.8 |

| try cocaine once or twice | 85.6 | 87.6 | 88.9 |

| take cocaine occasionally | 88.9 | 90.9 | — |

| take cocaine regularly | — | — | 95.8 |

| take LSD once or twice | 55.9 | 70.5 | 80.5 |

| take LSD regularly | 59.4 | 76.5 | 93.4 |

| try inhalants once or twice | 75.0 | 81.8 | — |

| take inhalants regularly | 81.3 | 86.9 | — |

| vape an e-liquid with nicotine occasionally | 60.8 | 58.0 | 59.2 |

| vape an e-liquid with nicotine regularly | 68.9 | 57.8 | 70.9 |

Social norms about alcohol and other substance use are tied to ethnic identity and stereotypes, as well. For example, there exist many drinking-related stereotypes about Irish Americans and Americans with Russian roots. Ethnic stereotypes can have a significant effect on an individual’s attitudes and personal decisions about drinking and drinking to excess. On the other hand, prohibitions around drinking to the point of intoxication or addiction may be strong in an individual’s cultural context. For example, norms against alcohol use contribute to primarily Muslim countries having the lowest prevalence rates of alcohol use globally (Michalak & Trocki, 2006). Or, for example, the use of alcohol by members of The Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints is generally discouraged in the Word of Wisdom which advises members about healthy living.

Alcohol plays an integral role in many religious, ethnic, and cultural ceremonies, but when it is included its use is typically characterized by moderation—drinking alcohol in moderation is permissible but drinking to intoxication is not in alcohol-involved rituals such as Shabbat, Passover, and the marriage ceremony in Judaism; substitutions for alcohol (grape juice, watered-down wine) are often accepted especially for pregnant women, young children, and persons in recovery from alcohol or other substance use disorder. Social norms disapproving of excessive alcohol use (misuse) can be a protective factor against alcohol use becoming an alcohol use disorder. In an analogous fashion, social norms concerning use of tobacco products, e-cigarettes/vaping, cannabis, and other substances may also have an impact on individuals’ decisions about initiating substance use, using substances to excess, or using substances under risky circumstances (e.g., driving or operating dangerous equipment, use during pregnancy, use by adolescents, use in combination with other substances). Shaping and communicating social norms is one target of preventive media campaigns.

Another perspective to keep in mind when thinking about social norms is an observation about homophily. The homophily principle means that, when free to choose, humans tend to congregate and associate with friends, acquaintances, and partners similar to ourselves. The saying is, “birds of a feather, tend to flock together.” The implication substance use implication is that individuals may choose to spend time in the company of others who engage in similar patterns of substance use/misuse. The homophily tendency shapes and reinforces the individual’s social norms about substance use, misuse, treatment seeking, and recovery—leading the individual to believe that “everyone” holds those similar norms because most everyone in their immediate social context does.

Social Structures

A number of theories draw from the science of sociology to explain the phenomena of substance use, misuse, and addiction. These theories “view the structural organization of a society, peer group, or subculture as directly responsible for drug use” (Hanson, Ventruelli, & Fleckenstein, 2015, p. 78).

Culture and subculture. Cultural systems are significant sources of socialization shaping attitudes, beliefs, and behaviors concerning substance use, misuse, treatment seeking, recovery, and stigma. The content of the values and belief systems of different cultural groups might vary, but many of the socialization processes by which these values and beliefs are shared and influence behavior are similar across cultural groups. Policy, as a form of intervention, is heavily influenced by a culture’s values and belief systems. For example, in the U.S. there has been a history of ambivalent philosophies concerning whether the problem of substance use is better addressed through punishment (criminal justice system responses) or treatment (physical, mental, and behavioral health system responses). Cultural systems are even responsible for defining “drugs” or “substances of abuse” in the first place. For example, in U.S. majority culture, hallucinogenic substances like peyote are defined as drugs of abuse. However, according to anthropologists, peyote religion among certain indigenous North American groups (e.g., Tarahuymara Indians of Mexico and various western Native American groups) defines this substance quite differently (Hill, 2013). Its use is acceptable under specific circumstances by specified individuals, including to treat medical conditions and in ritual ceremonies—a clear distinction is made between ritual/medical versus recreational use.

The impact of cultural systems is especially evident among immigrant populations. New Americans experiencing strong cultural identity and/or closeness to their culture of origin may exhibit less susceptibility to alcohol and substance misuse, whereas adapting to the new dominant American culture could be a risk factor for substance related problems (Banks et al., 2019; Perreira et al., 2019). This is particularly true when acculturation pressure impedes family closeness (Begun, Bares, & Chartier, in press). The protective force is dependent on the substance use-related norms of their original culture (Cook, Mulia, & Karriker-Jaffe, 2012). “The combination of having both strong spiritual beliefs and greater religious involvement provides a particularly strong protection against heavy drinking” (Begun, Bares, & Chartier, in press).

Subculture is about identifiable groups that form within a larger culture. The values, beliefs, attitudes, and behaviors within a subculture group may complement or contradict those of the larger cultural context. When they are contradictory, deviance theory may come into play. According to deviance theory, a person (or group) elects to engage in behaviors disapproved of by the conventional “majority” culture, often specifically because of that disapproval. Members embrace their deviance identity—the label becomes an important aspect of personal and group identity. Why would someone want to belong to a deviant subculture or group? For many, it is better to feel a sense of belonging somewhere, anywhere, rather than belonging nowhere—embracing/participating in deviant behavior feels like a small price to pay for admission to the group. For others it is a means of differentiating self from others—particularly from those who represent the conventional culture. It becomes a way of making clear to yourself and the rest of the world that you are your own person, distinct from your parents, siblings, family, neighbors, or others. Having strong prosocial bonds with members of the conventional or majority culture is a protective force against choosing to engage in deviance behavior—the extent to which a person desires approval and wishes to avoid disapproval of the people with whom they have these prosocial bonds helps them make choices that conform to convention (Sussman & Ames, 2008). It is also important to note that what is defined as “deviance” at one point in history, geographical location, or cultural system may later be redefined as the evolution or transition to a new conventional system. For example, attitudes toward cannabis use have shifted dramatically across many parts of the U.S. during the past decades such that a deviance position is now becoming normative.

Labeling theory suggests that other people’s perceptions of us, the labels they apply to us, have a strong influence on our own self-perceptions (Hanson, Venturelli, & Fleckenstein, 2015). The individual faces the choice of acting in accordance with the labels (e.g., continued drinking to excess when labelled as an “alcoholic”) or differently from/in opposition to the label (e.g., quitting drinking or drinking in moderation). In addition, theory suggests that when individuals have weak bonds to conventional society, there is less motivation to conform to conventional social norms and expectations. Hence, they are more likely to deviate from those norms when they have less “stake in conformity” than others who choose to behave in ways that comply with conventional norms (Sherman, Smith, Schmidt, & Rogan, 1992). Similarly, social control theory frames it this way:

“According to social control theory, strong bonds with family, school, work, religion, and other aspects of traditional society motivate individuals to engage in responsible behavior and refrain from substance use and other deviant pursuits. When such social bonds are weak or absent, individuals are less likely to adhere to conventional standards and tend to engage in rebellious behavior, such as the misuse of alcohol and drugs” (Moos, 2006, p. 182).

The roots of weak social bonds lie in social disorganization at the family, neighborhood, or school/work levels, and supervisory monitoring of behavior being lax, inconsistent or inadequate (Moos, 2006). On the flip side, strong family, school, work, religion, and other bonds to “traditional society” serve as preventive forces related to substance misuse (Moos, 2006).

The impact of “isms.” Issues of racism, classism, sexism, agism, and other forms of “ism” have a powerful impact on individuals’ experience of the social world, as well as on their physical environments. Experiences of oppression, discrimination, and exploitation based on racial, ethnic, social class, gender, gender identity, sexual orientation, religious, disability, or national origin factors are integral to understanding the social context of substance use, substance misuse, and substance use disorders. These forms of societal abuse fall along a complex continuum from the obvious, overt, or explicit to the subtle, covert, or implicit (Edmund & Bland, 2011).

Exposure to repeated instances of microaggression may contribute to substance use, as well. Ethnic and racial microaggressions are events that leave the person on the receiving end feeling put down or insulted based on their race or ethnicity—regardless of the intent by persons delivering the messages (Blume, Lovato, Thyken, & Denny, 2011). In a study of undergraduate college students, microaggression experiences were associated with both higher rates of binge drinking and experiencing more of the negative consequences associated with drinking (Blume, Lovato, Thyken, & Denny, 2011). Similarly, a study of college students demonstrated that the odds of regular marijuana use increased as a function of the number of microaggressions experienced (Pro, Sahker, & Marzell, 2017). And, again, the same relationship was observed in a study of Native American students and use of illicit drugs (Greenfield, 2015). Thus, it is important for social workers and other professionals to consider the heavy toll exacted on individuals who experience incidents of societal abuse, and how substance use may be related to these cumulative trauma experiences. Not only does this include those who experience it first-hand, but also those who witness it (second-hand).

“Isms” play a role in creating and maintaining marked disparities in opportunity and resources between social groups at the level of neighborhoods, schools, communities, workplaces, and populations. These include discrepancies in media portrayal, access or barriers to drugs, disparate exposure to advertising and media portrayals of drugs, access to desirable alternatives to drug use, availability and cultural competence of prevention and treatment options, and the consistency with which sanctions for drug-related activities are imposed (e.g., variable implementation of zero-tolerance policies or criminal justice system sanctions). Recall from Chapter 1 how the War on Drugs related to tremendous racial and ethnic disparities in the nation’s incarceration rates, for example.

Consider how social justice concerns and disparities function at the neighborhood and community level. The concept of social determinants of health has clear applications in substance use, misuse, and use disorders. Conditions that affect a wide range of health risks and outcomes include social, economic, and environmental factors through their impacts on behavior, risk exposure, and opportunity (CDC, 2018). For example, consider the difference between empowered and distressed neighborhoods to defend against the intrusion of illegal drug trafficking and the crime, violence, and exploitation that accompany drug trafficking, which in turn affect access to these substances, trauma experiences, and other risk factors for individuals’ substance misuse. With its accompanying adversities and deprivations, poverty may create an experience of chronic stress, which is a known contributor to substance misuse and relapse (Shaw, Egan, & Gillespie, 2007; Sinha, 2008). Poverty also may affect access to treatment for substance related problems (Begun, Bares, & Chartier, in press). In addition, alcohol and tobacco marketing is disproportionately directed toward low-income communities (Scott et al., 2008). Drinking among young men and women was positively related to the alcohol advertising exposure in their communities (Snyder et al., 2006). For example, men in low marketing exposure communities (5 exposures per month) consumed an average of 15 alcoholic drinks per month; men in high marketing exposure communities (45 exposures per month) consumed an average of 28 drinks per month. While the actual amounts consumed by women were lower (7 and 12 for the low vs high market exposure communities), the pattern was similar to that of men.

Not only do neighborhood factors increase residents’ access to substances, they influence social norms about substance use behavior. Also consider how difficult it becomes in many communities to gain access to evidence-supported prevention or treatment services that are accessible in terms of being affordable, close to home, culturally appropriate, and developmentally (age) appropriate.