Chapter 4.0: Psychological Models of Substance Misuse

Ch. 4.1: Cognitive and Learning Theories

The first group of theories examined in this chapter are those related to how thinking and learning are both involved in and affected by substance use, substance misuse, and substance use disorders. Cognition concerns the mental processes involved in a person’s knowledge, thoughts, and understanding of their experiences. Here we are not only interested in what a person thinks and believes, but also how—the processes and mechanisms that determine what someone knows, thinks, and believes. Psychology even has a word for thinking about thinking—this is metacognition.

Cognitive processing

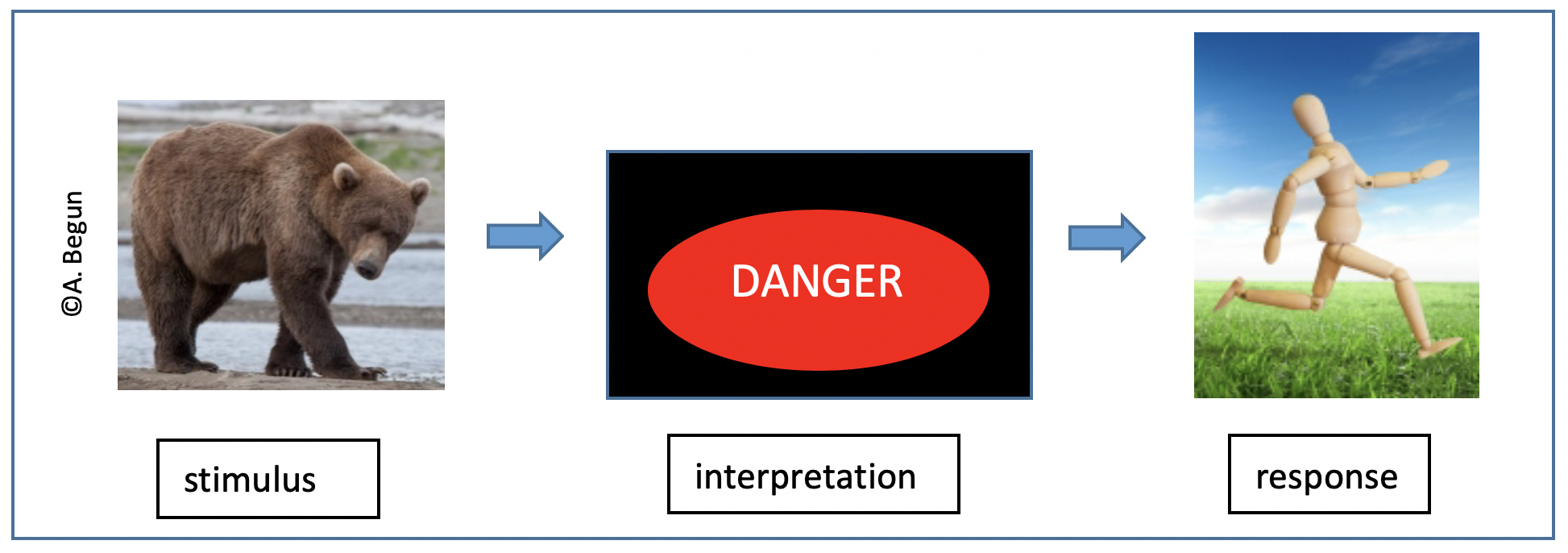

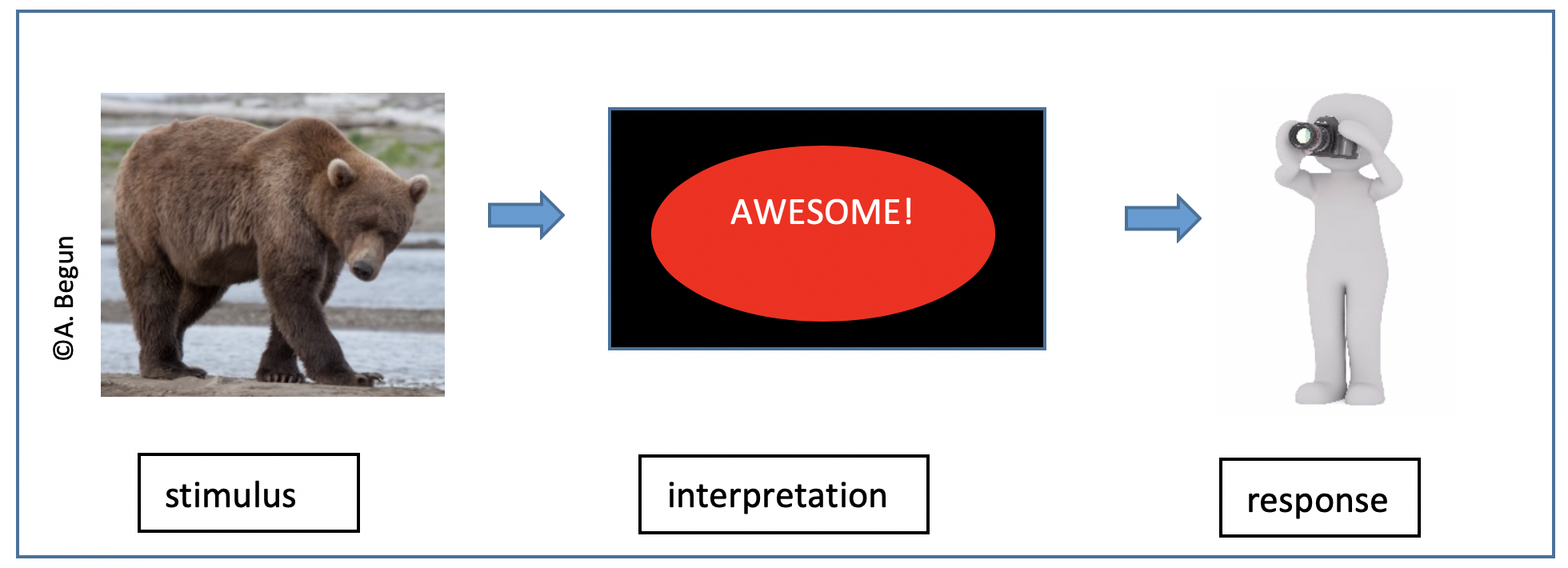

Cognitive processing has a great potential to influence human behavior. For example, how a person interprets a situation has a great deal to do with how that person will respond/behave in the situation. Here are different ways a person might interpret seeing a grizzly bear in the wild (stimulus) and how their response is dependent on that interpretation.

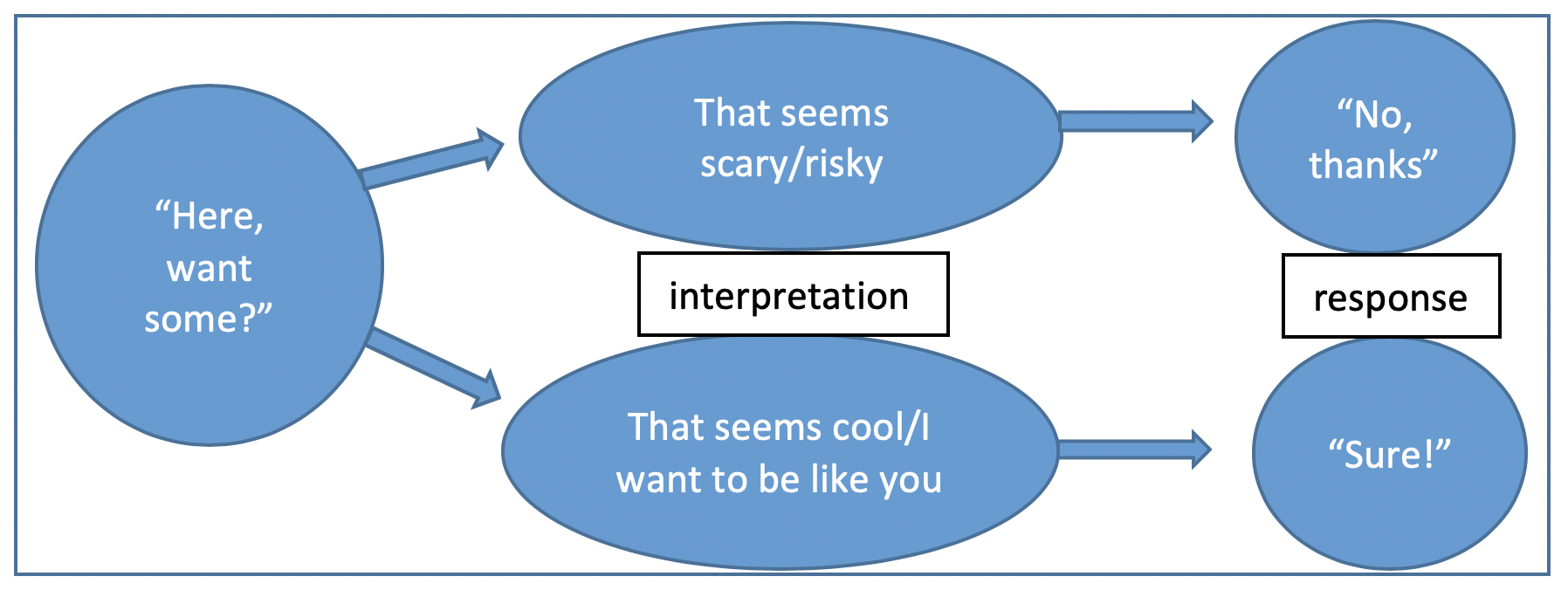

Now let’s apply this to an example possibly related to cannabis initiation. What happens when a person is offered alcohol, marijuana, or another psychoactive substance.

Here is another way in which cognitive processing—interpreting situations—is relevant. Consider the body of evidence concerning women becoming less aware of (or less uncomfortable with) situational cues concerning their risk of being sexually assaulted as their blood alcohol concentration rises to or above that specified as unsafe for driving—0.08 (Davis et al., 2009; Testa & Livingston, 2009). Substance use can impair a person’s interpretation of the potential riskiness of certain situations, which in turn can diminish their capacity for self-protection and early termination of coercive interactions. Practices like pre-planning for one friend designated as non-drinking during an outing and “having your back” may be employed by women who plan to engage in drinking activities; effectiveness is dependent on that one friend’s power to discern riskiness and effectively deter another from making an unsafe decision.

The alcohol myopia theory concerning intimate partner violence (IPV) behavior presents another example of how substance use might determine how situations are interpreted, which in turn influences behavior. The theory addresses the fact that IPV incidents are more frequent when one partner in a violent relationship has been drinking alcohol (Mengo & Leonard, in press). With alcohol myopia, a person might focus on immediate circumstances and events rather than placing them in a broader or longer-term context—becoming “nearsighted” in a situation—when alcohol has been consumed; this interferes with reasonable, accurate interpretation of what is happening. Alcohol myopia theory suggests that someone who has been drinking may be more likely to interpret another person’s behavior as threatening: the pharmacological properties of alcohol reduce capacity to derive meaning from complex information as happens in most social exchanges (Eckhardt, Parrott, & Sprunger, 2015). Interpreting an innocuous behavior as a threat leads to an aggressive behavioral response, including IPV.

Cognitive processes link to our feelings/emotions/affect, as well. For example, how we label our feelings has an influence on how emotions are experienced and how we behave in response to emotions. For example, if you have only a few labels available for describing and understanding affect (e.g., mad, sad, glad) then you have relatively few options available for how you behave in response; having more affective labels cognitively available for the emotions related to an event or experience offers a wider array of behavioral responses. Consider, for instance, what might happen in two different scenarios where someone gets a poor grade on an exam—it feels “bad” but what kind of “bad” or negative affect we identify determines how we might respond to the event. Some of the solutions or options are more productive than others:

|

Affect Label |

Bad=mad |

Bad=sad |

Bad= frustrated |

Bad= disappointed |

Bad= guilt/shame |

|

Response options |

quit; run away; blame others; threaten others; try to improve mood with exercise or substance use |

cry; mope; hide from the situation; try to improve mood with exercise or substance use |

problem solve; vent to others; “walk it off;” learn from mistakes for next time; negotiate |

problem solve; elicit sympathy from others; “walk it off;” learn from mistakes for next time; negotiate |

quit; run away; cheat or lie; apologize; try harder next time; elicit sympathy from others |

Individuals differ in how they cognitively label their affective (emotional) experiences which helps explain why they differ so much in how they respond to situations. For example, what is YOUR label for the affect this ambiguous screen bean character is experiencing?

Happy?

Terrified?

Excited?

Dancing?

Playing a sport?

Injured?

Falling?

Identifying what is happening has a lot to do with how we respond behaviorally and understanding this helps us understand a great deal about substance misuse—not only how affect might lead to substance use/misuse but also how substance use might alter emotions and the cognitive processes involved. [Note: the word “affect” here is not about effects—it is pronounced with the “a” like in apple, not like “uh” in apothecary (which is another word for drugstore).]

A great deal of emphasis in cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and other cognitively-based interventions centers on helping someone reinterpret situations, cues, and stimuli and develop new behavioral responses to those cues. Treatment strategies based on theories or models of the role cognition plays in addictive behavior (e.g., cognitive behavior[al] therapy, rational emotive therapy, cognitive skill building) have a common assumption: “Certain cognitive, emotional, and social skills are particularly useful for voluntarily steering one’s path out of addiction” (Heather et al., 2018, p. 251).

Rotgers (2012) identified a set of common basic assumptions among cognitive behavioral (CB) models and interventions related to substance use disorders, most of which could be applied to other forms of addictive behavior:

- human behavior is largely learned;

- learning processes leading to problematic behaviors also apply to changing these behaviors (classical conditioning, operant conditioning, modeling);

- environmental context factors play a major role in determining behavior;

- learning principles apply to changing covert behaviors (e.g., thoughts and feelings), not just overt behaviors;

- critical to changing behavior is the practice of new behaviors within the contexts where they will be performed;

- each individual person is unique and must be assessed with consideration of their experienced contexts;

- “The cornerstone of adequate treatment is a thorough CB assessment” (p. 114); and,

- “A strong working alliance is crucial to effective behavior change, regardless of therapy technique” (p. 115).

Information Processing

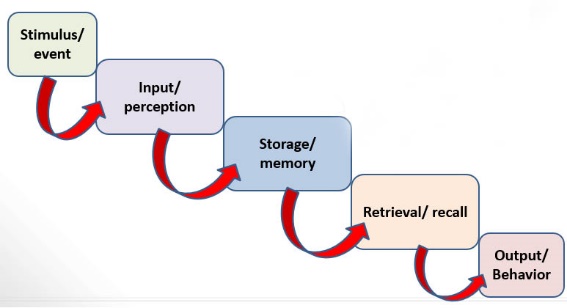

The information-processing model comes from cognitive psychology and helps explain (1) what a person “knows” about a substance, and (2) how a person’s substance use might affect behavior through its influence on perception, short- and long-term memory, and information retrieval. Not only does this model have implications for information/education intervention and how individuals behave while under the acute influence of certain substances, it also has implications concerning long-term (chronic) substance misuse and recovery from SUD. Information processing concerns how we initially take in information about our environment (or from internal biological cues). Then, what happens with that information and does it influence behavior? Let’s look at the information processing steps.

Perception. Before information, stimuli, events, or experiences can influence an individual’s behavior, several things need to happen in the processing the information. First, the person must attend to and perceive the stimulus through one or more of the five senses—the ways we generally perceive cues from the external environment (seeing, hearing, taste, smell, touch). However, we also perceive myriad cues from internal sources all the time (hunger, fatigue, arousal of “fight or flight” systems, etc.), whether or not we are aware of these internal cues. Regardless of the source, the first step in information processing involves “input” of information.

We know that different types of substances can have different effects on this perception phase of information processing. Have you ever noticed that conversations become progressively louder as individuals in conversation consume more and more alcohol? This is not solely about disinhibition. One effect of alcohol is to reduce the transmission of sound stimuli to the brain—people no longer hear their own voices as loudly so they compensate by talking more loudly. This is only one example of substance use influencing behavior through affecting perception.

Memory. Next, perceived information moves into memory storage—or not. Perceptions that do not move into memory are simply gone, eliminated from the system. They no longer have the power to influence an individual’s behavior. The first part of memory storage involves short-term (or “working”) memory. There is relatively little storage capacity in this working memory phase—information is lost after about 20-30 seconds unless it is transferred into long-term memory. Long-term memory involves storing information over time. Of interest here is that memories are not necessarily stored intact; they are highly susceptible to distortion and bias as they are stored. This is because humans tend to store memories in terms of their personal meanings and often are combined with other memories. This is part of why eye-witness testimony is so fraught with inaccuracies—the memories become distorted in the storage process. Human memory is not like a digital camera, storing images as they appeared when captured. For one person, some aspects will have more or less salience compared to other individuals, making them more or less memorable.

Retrieval. Depending on how memories were stored (long-term), they need to be recalled or retrieved in order to influence behavior. Cues from other stimuli or memories can “trigger” recall of a stored memory—for example, smelling marijuana might “trigger” recall of how it felt to use it or driving the car might “trigger” memory of how it felt to smoke a cigarette while driving. This is an important aspect of cravings. On the other hand, evidence concerning state-dependent learning suggests that retrieving information is easiest and most accurate when conditions are very similar to when the information was originally introduced/learned. In other words, information or skills learned and easily retrieved while under the influence of alcohol or other substances may be more difficult to retrieve when a person is in a different (unaltered) state of consciousness (Overton, 1984). Vice versa, what is learned under normal conditions may not be recalled when in an altered state. Thus, a person in recovery may need to relearn information or skills originally learned while under the influence of substances.

Substance-distorted information processes. In addition to examples of how each step might be affected by substance use, psychoactive substances can profoundly affect overall information processing. For example, information processing overall is slowed among men engaged in chronic excessive alcohol consumption compared to men who do not drink alcohol excessively, beginning with perception and carrying through the decision-making and response (behavior) phases (Kaur et al., 2016). This, in part, explains delays in reaction time and the risk of driving a vehicle under these conditions. Fortunately, affected cognitive functions improve in many individuals during months to years of abstinent recovery (Cabé et al., 2015). In addition, consider the possibility that individuals in early recovery may not effectively process information delivered through treatment/intervention efforts with a heavy cognitive component—these strategies are better processed a few weeks into recovery (NIAAA, 2001).

Learning Theory

Learning theories represent one set of psychological principles that have had a strong influence on our understanding of substance misuse and SUD. Relevant learning theories include both operant and classical conditioning principles.

Classical Conditioning. Pavlov demonstrated classical conditioning in his experiments with dogs. The process involved learning where a previously neutral stimulus paired with a naturally potent (unconditioned) stimulus came to elicit the same response (conditioned stimulus) as the natural (unconditioned) stimulus. In Pavlov’s experiments, this meant the ability to trigger a salivation response to the sound of a bell after repeatedly pairing the sound with presentation of food. Salivating is a naturally occurring response by dogs to having food presented (unconditioned stimulus). Repeatedly pairing the sound of a bell with the presentation of food, which elicits salivation (unconditioned response), eventually makes the dog salivate in response to the bell alone—the bell has become a conditioned stimulus and salivation to the bell (rather than food) has become a conditioned response.

The same learning principle may apply to certain substance use phenomena. For example, drug paraphernalia, specific settings or environments, certain people, or even certain emotions may become conditioned stimuli eliciting a desire to use the substances previously associated with them. Unfortunately, it is challenging to unlearn strong conditioned pairings, especially those with particularly powerful feelings attached. Fortunately, it is possible to train new pairings, such as training a person to use relaxation, breathing, mindfulness, and delaying techniques in response to the feelings stimulated by the conditioned stimuli.

Operant Conditioning. Another set of psychological learning principles with a profound impact on substance misuse is operant conditioning. Operant conditioning is all about rewards and punishments. If someone experiences a positive consequence as the result of using a particular substance, the reward (positive reinforcement) increases the probability of repeating that behavior again in the future. Experiencing a negative consequence (punishment) decreases the probability of repeating that behavior again in the future. Considerable confusion revolves around the concept of negative reinforcement, and because this is an important process in substance misuse negative reinforcement warrants some closer attention. Let’s start with this chart comparing consequences and effects in operant conditioning.

|

|

Consequence |

Effect |

Label |

|

BEHAVIOR |

provide favorable stimulus (reward) |

increased probability of repeating behavior |

positive reinforcement |

|

remove unfavorable stimulus (reward) |

increased probability of repeating behavior |

negative reinforcement |

|

|

provide unfavorable stimulus or remove favorable stimulus (punish) |

decreased probability of repeating behavior |

punishment |

|

On the far left, we have a person engaging in a specific behavior—exercising, for instance. Looking in the middle and to the right we see the possible consequences, effects of the consequences on future behavior, and what we call this type of operant conditioning learning.

- If the person exercises to the point of experiencing endorphin release in the brain, the positive experience is rewarding. In other words, the exercising behavior was positively reinforced which increases the probability that the person will engage in that behavior again in the future—chasing down that positive reinforcement experience in the form of endorphin release.

- If the person aches and is winded instead, the experience is quite negative. In other words, the exercising behavior was punished which decreases the probability that the person will engage in that behavior again in the future.

- What if the person starts out with negative feelings—may they feel anxious or somewhat depressed (negative experience)—but manages to get active in some form of exercise (behavior). If the anxiety or depressed mood is removed, the exercising behavior has been rewarded. Rather than providing positive reinforcement (as we saw in the first example with endorphin release), the behavior removed a negative state. This is still a form of reinforcement because it increases the probability that the behavior (exercising) will be repeated in the future. It is not “positive” reinforcement (delivering a positive reward; instead it is called “negative” reinforcement (removing a negative stimulus).

- Technically, punishment could be either positive (delivering something negative) or negative (removing something positive—like making someone pay money in fines). However, we do not use those terms much. Punishment is punishment—the opposite of reinforcement—whether it is taking away something positive or delivering something negative.

Now, let’s consider this operant conditioning paradigm in terms of alcohol or other substance misuse.

- A person is offered cigarettes by peers and feels accepted by them (positive reinforcement) when joining them in smoking together. Result: more likely to smoke with friends in the future.

- A person drinks to the point of throwing up (punishment—applying a negative consequence). Result: less likely to drink to excess in the future.

- A person has to pay heavy fines and pay lawyers/legal fees for driving under the influence of marijuana (punishment—taking away a positive). Result: may be less likely to drive under the influence in the future.

- A person feels nauseous with anxiety and finds that the anxiety and nausea go away when using cannabis (negative reinforcement). Result: may be more likely to use cannabis to dispel anxiety/nausea in the future.

This last example plays a role in what we learned about withdrawal symptoms and tendency to relapse (or at least slip) during recovery from SUD. A person whose body has come to depend on a substance like alcohol or heroin being regularly administered will experience withdrawal symptoms if the substance is no longer used. Withdrawal symptoms are a very aversive (negative) experience which makes it a quite punishing consequence for quitting use—the person is less likely to maintain the “quit” behavior as a result. Then comes part two of the problem: negative reinforcement. If the person does resume use, even one slip, the punishing withdrawal symptoms momentarily subside—this consequence rewards using again. So, in operant conditioning terms we have two forces pushing for relapse as a result of withdrawal symptoms—the punishment for quitting that the withdrawal symptoms introduce, compounded by the negative reinforcement for using again. You can see why operant conditioning is so important both in the process of substance use becoming substance misuse or SUD and in the difficulty of recovery, as well.

A little more about reinforcement paradigms. While operant conditioning can make the story of substance misuse clearer, there do remains some complicating factors. These have to do with (1) consequence salience, (2) consequence timing, and (3) consequence sequencing.

Salience. A single reward or punishment may not mean the same thing to everyone—it may have different salience for different individuals. For example, M&Ms may be perfect rewards for some toddlers in potty training while other toddlers really do not care about candy; they are better rewarded with smiley faces drawn in marker on their hands and knees. In training a new behavior, it is critically important to find the reinforcements that are most powerful for each individual. Heightened reward sensitivity in the adolescent brain might make the reinforcing aspect of drinking, vaping, or using cannabis more rewarding than for older individuals. Likewise, punishments may have different power (salience) for different individuals—charging fines may be more punishing to some than to others, for example. Or, for instance, nicotine withdrawal may be experienced more negatively by some individuals than by others, which has an impact on differences in their ability to cut down or quit smoking.

Timing. The strongest effects of reinforcement or punishment on learning and future behavior happen when the time lapse between the behavior and the consequence is very short. Substances that get to the brain quickly through administration methods like inhaling, injecting, or “snorting” have a more powerful influence on the reward circuits than substances arriving through more delayed delivery routes (ingestion requiring digestion). In other words, the faster the substance arrives at the active sites in the brain, the stronger the reinforcement for using it.

On the other side of the timing issue, you may wonder why experiencing a hangover does not always lead to someone learning not to drink, or at least not drinking to excess. Unfortunately, the consequence (hangover) is delayed by many hours from the behavior (drinking). This time lag erodes (ruins) the power of the punishing consequence to be a strong influence on future behavior—“time is the enemy.”

Sequencing. The other problem with relying on the punishing experience of hangover to influence future behavior is that it is not the first consequence experienced. The positive reinforcements associated with drinking being experienced first imbues them with more power to influence future behavior than the punishing consequences that arrive later. First “place” consequences are usually the winners.

Negative attention. One last point about learning theory warrants consideration. The social world around us is a rich source of positive reinforcement, negative reinforcement, and punishment. We would expect that exhibiting a behavior for which the consequence is social approval would likely be repeated—it was positively reinforced. We would expect that a behavior met with scolding would less likely be repeated—it was punished. However, we sometimes see an odd paradox with this latter example. Sometimes, any attention, positive or negative, is rewarding. Instead of a scolding being punishing, it could be reinforcing in some instances. Furthermore, sometimes when a behavior is ignored, the individual interprets the lack of punishing response to be a tacit approval of the behavior—which, in turn, means it is more likely to be repeated. Sometimes ignoring a behavior leads to its extinction. Other times ignoring a behavior leads to its encouragement.

Social Learning Theory

Classical and operant conditioning theory are somewhat constrained by the necessity for the individuals to directly experience consequence in order for them to have reinforcing or punishing potential. Humans (and many other species) are also capable of learning through observing consequences to others. This is one critical addition from social learning theory. For example, a person does not need to experience a fentanyl-influenced opioid overdose in order to develop concern about fentanyl contamination—witnessing this happening to someone else, or perhaps even learning second-hand about someone else’s experience—observational learning—can have an influence on their own drug-testing behavior (a harm reduction strategy). Observational learning plays a role in the development of expectancies.

Many complex behaviors are learned through modeling and imitation—aspects of observational learning—rather than learning each individual element of the complex behavior one-at-a-time. For example, smoking a cigarette or e-cigarette (“vaping”) is a complex behavior—it involves engaging in a series of coordinated behavioral steps. Learning to do this is not “taught” one step at a time as in an instructional manual for assembling a toy or piece of furniture. It is learned as a behavioral sequence, typically through observation of behavioral models.

The experiments of Albert Bandura demonstrated the power of observational learning through imitation of behavioral models. Children not only learned and imitated specific acts of aggression toward a Bobo doll modelled for them (hitting, kicking, pushing), they learned to express the entire class of aggression toward the Bobo doll—aggressive behaviors that were not specifically modelled for them, like hitting it with another doll. Taking this to the substance use arena, consider a parent modeling alcohol use as a strategy for coping with stress. Children may not learn only to consider using alcohol under stressful circumstances, they may learn to use substances in general—the class of substance use/misuse behavior, beyond the specific drinking behavior. [If you are unfamiliar with Bandura’s Bobo doll aggression research, you might enjoy reviewing the 5-minute video available at http://www.teachertube.com/viewVideo.php?video_id=131805 ].

Imitation of modeled behavior is a power mechanism of learning and socialization throughout the lifespan. Social referencing concerns a person who, in ambiguous or unfamiliar situations, relies on observing others’ behavior to know how to respond. We see social referencing in young children when they, together with a parent, are approached by a stranger: the child turns to watch and listen to the parent’s reaction to tell them how to interpret and respond in the situation. Social referencing may play a role in how individuals respond to substance-related situations—watching peers, for example, respond to someone offering alcohol or other substances in order to know how they might respond themselves. Social referencing involves using the other person’s behavior as a cue in interpreting a novel or ambiguous situation for oneself.

Another important aspect of social learning theory concerns that concept of salience, again. This time salience refers to the desirability or relevance of a specific model to the individual—this determines the likelihood of imitating that model. For example, an adolescent might find peers to be more salient models than they find teachers to be; parents remain salient for many adolescents and emerging adults but peers or other highly salient models may become more salient in certain situations. Salience of models might differ in terms of how much “alike” the observer feels they and the model might be—in terms of age, gender, sexual orientation, social status, or other “like me/not like me” variables. It also may differs in terms of how “desirable” (e.g., likeable, “cool,” popular, respected, successful, counter-culture/deviant, from my community) the model appears to the observer. Salience is always in the “eye of the beholder.” Knowing this about social learning theory helps us understand not only why someone might imitate substance use/misuse, but also why they might imitate NOT using/misusing substances. We generally are more likely to imitate salient behavior models—those we wish to be like—than to imitate other models.

These are reasons why adopting a “do as I say, not as I do” strategy is less effective than might be expected: learning is powerfully influenced through social learning principles like observational learning, imitation/modeling, and social referencing.

Theory of Reasoned Behavior

In many areas of health psychology and health promotion, professional practices are based on theories of reasoned behavior, rational choices and/or behavioral economics. In general, though this is grossly oversimplified, the theory is that individuals will make rational choices when faced with a set of behavioral options. In other words, a person will weigh the pros and cons, advantages and disadvantages, or costs and benefits of each choice before choosing to behave in a certain manner, selecting the option that is most advantageous (or least disadvantageous) among the available choices. A person will choose to engage in an addictive behavior, like substance use or gambling, if they perceive it will better meet a need than the other available options (McNeese & DiNitto, 2012).

In regards to the decision whether or not to use alcohol, cannabis, or some other substance, an individual would engage in an internal mental debate about the possible positive versus negative outcomes—feeling like part of the group using the substance and positive feelings the substance might create would be weighed against the cost of getting the substances, what happens if your family finds out, possible legal ramifications, and so forth. Interventions from this theory base would be geared towards informing individuals about, and highlighting, the potential health (or other) risks associated with use of the substance(s). The assumption is that if they understand the risks they will make the “wise” decision not to engage in this behavior—the costs would outweigh the benefits. In addition, intervention might be geared toward helping the individual find other means of achieving the desired benefits at less risk/cost (e.g., getting the desired emotional response from exercise rather than substance use).

Unfortunately, we all know instances where someone (maybe even ourselves) made a choice that was not good for us—perhaps for no good reason at all. Perhaps they underestimated or misunderstood the risks/costs or the probability of the negative outcomes. Perhaps they decided the benefits outweighed the risks/costs despite the information provided to them. Or, perhaps, they were motivated by some other reasons to throw caution to the wind and made the disadvantageous decision anyway. The point is that individuals’ decision making does not always seem well-reasoned and rational.