Chapter 7.0: Theory Integration, Transtheoretical Model, and Risk/Protective Factors in Substance Misuse

Ch. 7.3: Theory Integration in the Transtheoretical Model of Behavioral Change

A great deal of effort both in our course and in research has been directed toward understanding the processes involved in substance use initiation and the progression from use to misuse and substance use disorder. At this point, we examine a model concerned with processes of change and recovery—moving back from problematic and disordered substance use into recovery. The model we focus on in this chapter is known as the transtheoretical model of behavior change (the TTM for transtheoretical model, or sometimes the TMBC for the transtheoretical model of behavior change). The model originally emerged in transtheoretical analysis of psychotherapies (Prochaska, 1979; Prochaska & DiClemente, 1982) and continued to evolve during the 1980s and 1990s based on research concerning the process of change in smoking behavior (Prochaska & DiClemente, 1983) and expanded to include other addictive behaviors (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). It has been applied across disciplines (social work, psychology, medicine, nursing, physical therapy, occupational therapy, and others) and across a wide array of behaviors, including but not limited to individuals making changes in their smoking (tobacco), alcohol use, adhering to a medication or medical treatment regimen, dieting, exercising, safe-sex, and intimate partner violence behaviors.

Use of the word “transtheoretical” in the model name reflects its theoretical inclusiveness and that it integrates and applies across theories. The transtheoretical approach represented an important shift in emphasis among intervention options towards identifying mechanisms of change and the elements or factors common across a variety of intervention approaches. The TTM’s developers distilled from research and clinical observation a set of principles describing behavior change processes and factors that facilitate or pose barriers to achieving change goals. The TTM identified a series of five stages in the typical cycle of change, common processes involved in intentional behavior change, and implications for intervening to support individuals’ intentional behavior change efforts.

Stop and Think

While you review the remainder of this chapter, consider a specific behavior that you have wished or tried to change in the past. See how the model seems to fit your own experience with intentional behavior change (something like getting more sleep, drinking more water, using less electricity, praising your partner or kids more often, spending less money on coffee, stop biting your fingernails, expressing gratitude for small favors others do for us—it does not have to be about an addictive behavior).

Stages of Change

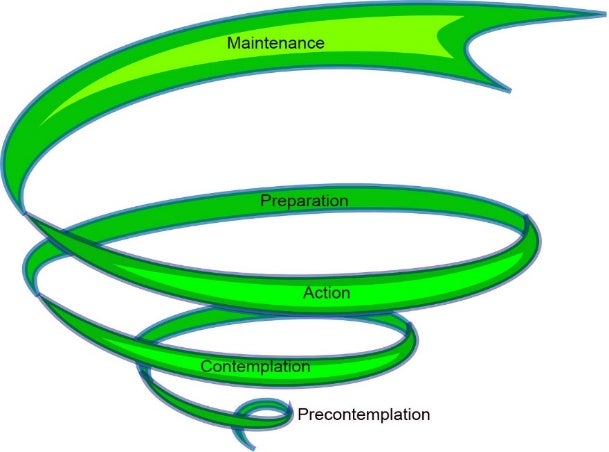

Like most stage theories, the TTM identified a series of progressive stages that are qualitatively distinct from each other. Originally, the TTM specified four stages: Precontemplation, Contemplation, Action, and Maintenance; data reanalysis led to specification of a fifth stage, Preparation, between Contemplation and Action. An important difference from many other stage theories is acknowledgement that individuals do not move through the stages in a linear “upward” fashion but that they often cycle upwards and downwards through stages as they work to achieve their change goals (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). For example, a person perhaps beginning in Precontemplation may progress through some of the other stages, return to prior stages (including back to Precontemplation), and progress again over time, and that this cycle may repeat multiple times before the desired change goal is ultimately achieved. In research concerning smoking cessation, three to four Action attempts occurred before individuals were able to quit smoking for the long-term (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992)—in other words, relapsing and falling back to earlier stages is normative, not atypical. A determining factor in how quickly someone is able to again move forward in the process concerns how relapse is handled: if seen as a failed attempt, the person may return to precontemplation and remain there for a lengthy period; if seen as an opportunity to learn from one’s mistakes, identify potential pitfalls and solutions, the person may move more quickly back into action instead. In fact, one criticism of the TTM is that individuals may move between stages so quickly that assessment tools are rendered inaccurate, and that a person may be situated between stages rather than in a single stage.

Another observation made by the model’s developers was that what a person learns about changing one type of behavior may help them learn what will or will not help them change a different type of behavior. However, if someone is concerned about changing two or more behaviors at the same time, the change process for each will most likely differ—in other words, a person may be in one stage for one behavior change effort and a different stage for another. Consider, for example, that someone wishes both to quit smoking cigarettes and to quit drinking alcohol to excess. Each of these change attempts, although occurring at the same time, will progress on its own trajectory (Velasquez, Crouch, Stephens, & DiClemente, 2016). The individual may move through the cycle more quickly with one behavior compared to the other and may spiral back and forward more times. It is difficult enough to change an addictive behavior; it is far more difficult to change more than one at a time.

The five stages identified in the TTM distinguish between the different behaviors, attitudes, experiences, and motivations representing each stage.

Precontemplation. The hallmark of Precontemplation is the absence of an intent to change the identified behavior, at least not in the foreseeable future. This includes individuals who are un- or under-aware of a need to make changes. It also may include someone who wishes they could change but does not seriously intend to make the changes wished for. This stage also may involve resistance to change in response to pressure from others. For example, if a person is compelled to quit smoking while incarcerated in jail or prison, that individual may only comply as long as extrinsic (external) pressure is applied. There may be no intention to extend the change in behavior to the post-release period. The kinds of statements endorsed by someone in this stage include denial that a problem exists, that the behavior is not problematic, or that it is “their” business and no one else’s concern. On the other hand, they may engage in blame about the problem (“If I drink too much, it is because you are always nagging me”) or focus on an inability to change (“I have tried to quit smoking too many times, face it—I am just a failure” or “It is in my genes, I am destined to die this way.”)

Contemplation. A person in the Contemplation stage demonstrates awareness of a problem and serious consideration of making a change without making a specific change commitment. One characteristic of the Contemplation stage is the person struggling with the “pros and cons” dilemma—the advantages of making the change versus the disadvantages. For example, someone might realize the health benefits of changing their binge drinking and appreciate the amount of money that could be saved by making a change, but at the same time recognize that they like drinking, would be lonely without binge drinking with “buddies,” and that it will take a great deal of effort to make this change (see discussion of decisional balance below). An intention to make significant change within the next six months is considered a characteristic of Contemplation. However, individuals may remain in Contemplation for lengthy periods (despite the “within six months” intent) without moving further in the process—for two years or more among a group of participants in a smoking study (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992). Examples of statements that a person in Contemplation might endorse generally include awareness of a problem and a desire to make a change: “I think I may have a problem with my drinking,” “I am really starting to feel the effects of my smoking when I try to walk upstairs,” “I am getting to the point where I can’t keep doing this to myself anymore.” A person in Contemplation might engage in information-gathering, exploring options for how to make the desired change (even looking into formal intervention/treatment options), but not actually engage with or commit to any of them.

Preparation. The Preparation stage extends beyond an intent to change to include early change behaviors toward the goal of taking serious action within the next 30 days. They will have set a plan in motion, even if not actively engaged in it yet, and have set a target day/date for the action to begin. For example, the person may enroll in a change-focused program, identify a specific change strategy or plan, and may begin taking “baby-steps” toward the change goal. For example, a person preparing to quit smoking may purchase supply of nicotine replacement “patches” or gum, schedule an appointment for prescription smoking cessation medication, register with a smoking cessation program. In addition, they may break their cigarettes in half to smoke less when they do smoke and gather together all their “stashed” cigarettes into one, visible collection. They may tell friends and family to refuse their requests to “bum” cigarettes and not invite them to share a smoking session.

Action. The Action stage is characterized by a person actively taking very specific, concrete steps to change the target behavior and keep the change momentum going. For a behavior as complex as quitting drinking, for example, the person may engage in a host of strategic alternative behaviors: avoiding the people, places, and situations that tempt them to drink; applying strategies for controlling their mood (e.g., mindfulness practices) and stress management (e.g., exercise); grocery shopping online to avoid impulse alcohol purchases in the store. Additionally, they may have new ways of rewarding themselves for each positive step taken (e.g., putting money that would have been spent on alcohol into an account toward a positive goal; celebrating their “sobriety birthday” each week, then month, then year), and reminding themselves of their accomplishments (e.g., journaling their efforts, experiences, and progress). Action is very often the emphasis in treatment programs—teaching, training, and practicing the new skills. A person in Action has specific skills and behaviors to substitute for and manage the old, problematic behaviors and they consciously act to implement these new behaviors. Action, by definition, lasts for at least 6 months and may last much longer for some individuals and some behaviors. Big changes in complex behaviors do not happen overnight. This is a person engaged in multiple, sometimes heroic, action efforts as they are fighting to achieve their change goals.

Maintenance. Once a person has engaged in action behaviors for at least 6 months, they may move into a Maintenance phase—a period of continued vigilance against relapsing to the past behavior. Individuals continue to engage in relapse prevention activities, but it differs from the Action period in that the new changed/alternative behaviors, attitudes, and experiences are becoming routine and feel relatively natural. They require less effort to maintain. During maintenance, a person continues to be aware that it would take only one “slip up” action to undo their hard work but takes many daily “non-actions” to avoid relapse—consistently avoiding temptations and relapse triggers, engaging in competing alternative behaviors, and managing temptations and relapse triggers when they do appear. A person in maintenance is not “cured” as long as there are temptations or craving experiences—the maintenance period may persist for a very long period, possibly indefinitely for some individuals. However, a person who managed to quit smoking cigarettes (for example) may reach a point when there is no longer any desire to pick it up again, none of their old cues trigger a temptation or desire to smoke, and they self-identify as a non-smoke (rather than an ex-smoker), even in periods of stress/distress. At the point where the changed behavior is relatively effortless, the person may be considered to have moved beyond maintenance.

Relapse. Understanding the change process is incomplete without recognizing what relapse is and how it might be addressed. Ideally, we want to prevent relapse to the “old” behavior whenever possible; but as the evidence indicates, relapse happens (may even be a “norm” rather than an exception) and what happens in response to relapse matters very much in the future of a change effort. First, a distinction is made between a recurrence (“slip”) and a full-blown relapse event. A lapse or “slip” is time/event limited—doing it once or more times for a short period, quickly regretting the lapse, and getting back to renewed action. The circumstances surrounding a lapse can be effectively used as a learning experience to strengthen the ongoing change effort for the future. Relapse refers to a return to the old pattern of behavior with no intention of changing again—spiraling back to Precontemplation, especially if the person despairs of ever being able to successfully change. A lapse, relapse, or impending relapse can happen at any point in the change process.

Relapse is a process (rather than an event) that starts before substance use occurs again—it is “a gradual process with distinct stages” (Melemis, 2015). The relapse process may begin days or even months before the actual substance use relapse behavior occurs and can be conceptualized in three parts.

- The “emotional” process of relapse is characterized by a lack of emotional, psychological, and physical care (Melamis, 2015). This includes basic physical care (diet, sleep, exercise, hygiene), as well as emotional and social “care” activities. This contributes to the kinds of negative emotional states involved in substance misuse—stress, tension, restlessness, anxiety, fatigue, irritability, and discontent.

- The “mental” relapse process concerns declining cognitive resistance to relapse, increased sensitivity to “use” messages, framing past use more positively (“glamorizing”) and minimizing consequences, entering into bargaining about use (“I’ll only do X and nothing more” or “It will be okay on vacation, just not in my regular life” or “if I stick to beer and avoid “hard” liquor, it will be okay”), scheming/lying, and actually planning a relapse/looking for relapse opportunities (Melamis, 2015). While occasionally thinking about using substances again is a common experience during recovery, a warning sign is when these thoughts become frequent, detailed/specific, and intrusive/insistent in nature.

- “physical” relapse involves actual substance use/misuse—a return to uncontrolled substance use. One-time substance use may not lead to further uncontrolled use or it may contribute to the emotional and mental relapse processes that, in turn, lead to physical relapse. Relapse prevention involves anticipating and addressing all three parts—emotional, mental, and physical—and having in place plans for identifying/assessing and developing exit strategies for the different threats. This likely includes engaging supportive significant others (asking for help from trusted family/friends; participating actively in recovery-oriented or mutual support groups) and engaging in treatment interventions designed specifically around relapse prevention (e.g., cognitive behavioral interventions and skill building).

Concerted intervention effort might be directed toward relapse prevention, particularly during the maintenance stage.

Change Factors

Threaded throughout the change process are a trio of factors: decisional balance, self-efficacy for change, and timing of different intervention/change promoting strategies.

Decisional balance. Relevant throughout the change process, but particularly in the Precontemplation and Contemplation stages, is the concept of decisional balance. The TTM relates to motivation for engaging in the change process. It recognizes that a person who is motivated to make an intentional behavior change may also be motivated NOT to make the change. There exist costs and benefits on all sides of the decision and a person may see-saw back up and down as the balance shifts toward or away from making the change effort. There are four dimensions of which the person is aware and that have implications for the likelihood of embarking on a change effort:

|

Not Changing |

Changing |

||

|

|

Pros |

Cons |

|

|

Pros |

ambivalence |

no change |

|

|

Cons |

yes change |

ambivalence |

|

Decisional balance underlies the ambivalence identified and addressed in motivational interviewing (MI). Eliciting and sustaining motivation for change often requires addressing ambivalence, not just emphasizing the advantages of changing and disadvantages of not changing the behavior. Decisional balance is particularly impactful in the Precontemplation, Contemplation, and Preparation stages, but continues to have a role across the process.

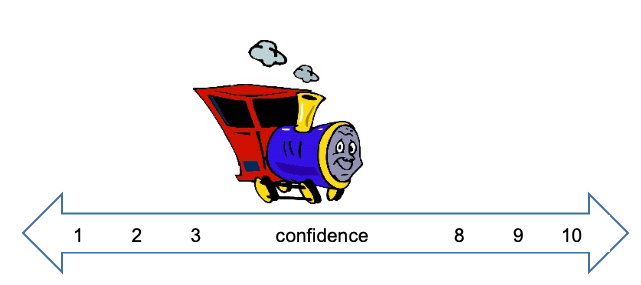

Self-efficacy for change. Another cognitive process involved in each stage of the intentional behavior change process concerns a person’s belief that change (or maintaining change) is possible: their self-efficacy for making or sustaining the change goal. Like The Little Engine that Could, self-efficacy ranges from “I can’t” to “I think I can” to “I know I can” and makes a difference in motivation at all stages of the change process. Someone might be in the Precontemplation stage (no plan to change) because they do not believe it is possible, despite being aware of that their behavior is problematic. This may be because they have made unsuccessful change attempts in the past and feel it is a hopeless goal. Two strategies for assisting with motivation in this situation are (1) focus on ways that they have succeeded in the past, including any positive steps they may have made in changing this behavior or any other behaviors they may have been able to change in the past, and (2) examining how others most like themselves have managed the change process. A conversation that might elicit self-efficacy involves a “change ruler” whereby a person indicates on a scale from 1-10 how confident they are in their ability to make the desired change in a situation of temptation. Rather than focusing on how far from 10 they are, the value lies instead on exploring why the rating is greater than 0—what the person may have going for them.

Intervention timing. Matching intervention strategies to “where the person is” with their change process, achieving the right timing, is an important consideration related to the TTM (Velasquez et al., 2016). “Action-oriented therapies may be quite effective with individuals who are in the preparation or action stages. These same programs may be ineffective or detrimental, however, with individuals in precontemplation or contemplation stages” (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992, p. 1106). Similarly, individuals ready for action and learning change-based skills may become frustrated and drop out of interventions aimed at raising their awareness of the problem and why they might need to make change—they are already past that point and ready to engage actively in change efforts. In other words, intervention efforts should be timed so as to connect to the relevant change goals at any point in time. Ideally, these fit together like puzzle pieces, and are adapted as the situation changes over time. For example, in efforts to move from Precontemplation to Contemplation, consciousness raising might be appropriate, whereas Action-oriented efforts might include creating a system of positive reinforcement for changed behavior and other change skill sets (Prochaska, DiClemente, & Norcross, 1992; Velasquez et al., 2016). While much of the TTM approach and motivational interviewing reflect the individual’s thoughts, feelings, experiences, and behaviors, it can effectively be applied in group work settings (Velasquez et al., 2016).

Stop Think

Thinking about the material you read in this chapter and the specific change effort example you were considering:

- What did you conclude about how the model seems to fit your own experience with intentional behavior change?

- How did you experience the stages of change and did you follow a single progression or spiral up/down the cycle?

- How did decisional balance, ambivalence, and self-efficacy for change look in your chosen example?

- What did or could have helped and what might have gotten in the way of your change effort?

- What does this tell you about possibly supporting others in their efforts to change, even to change addictive behaviors?